Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold.

(from John Keats’s ‘On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer’)

(This report is dedicated primarily to an analysis of the 1987 movie The Fourth Man. I append an important correction to my recent observations about Anthony Blunt, and seek reader comments. I also mention here that an enormous trove of files was released earlier this month by the National Archives, including records on Philby, Blunt, Cairncross, and Litzy Friedmann. Fortunately, all these records have been digitized, so access is easy. I have made a brief inspection of these to look for obvious newsworthy items, but since I am still working my way through the undigitized Burgess, Maclean and related Foreign Office files, it may be a while before I can give them the treatment they deserve.)

Contents:

Introduction

Friendship and Betrayal

‘The Blunt Affair’

‘The Fourth Man’: The Storyline

The Sources

Chapman’s HOMER

Conclusions

Anthony Blunt: A Correction

* * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

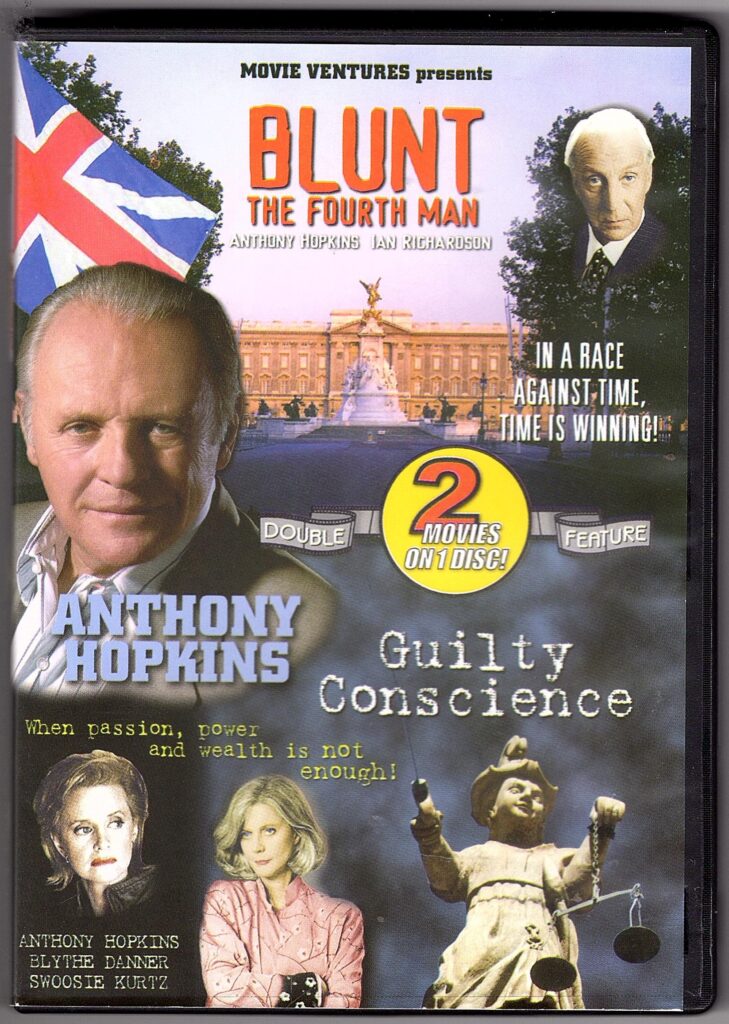

Andrew Malec encouraged me to view the 1987 TV movie The Fourth Man, from a screenplay written by Robin Chapman, about Anthony Blunt and his role in helping Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean escape in 1951. I resisted at first: it sounded rather dire, and I deemed that watching it might have been bad for my mental health. I had watched another series, The Cambridge Spies, when it came out in 2003, and remember it now as fairly dreadful. (I have not yet watched Philby, Burgess and Maclean, starring Derek Jacobi and Anthony Bate, made in 1977, from the pre-Blunt era.) Yet Andrew persisted, and I had to admit that anything with Ian Richardson in it (and, to a lesser extent, Anthony Hopkins) was probably worth seeing. So I acquired the DVD, viewed it, and, with some misgivings, even enjoyed it. It occurred to me that, at the time of its release, the movie might have influenced a number of persons who had hazy notions about the whole ‘Missing Diplomats’ fiasco, and I thus thought it would be worthwhile to conduct a deep analysis of it. I also thought it was a good place to start a project to try to unravel many of the anomalies and paradoxes in the ‘Third Man’ story that had vaguely occupied my mind for many years.

Some of the questions that exercised me were the following:

- What was the storyline, and what lesson did it draw from the episode?

- On which sources was the storyline based?

- What errors did it make, given the paucity of archival information available at the time?

- Where did the storyline break out into new activities and events?

- Was the imagination in such ventures justified?

- How should the movie be assessed in light of what we know almost four decades later?

Before I tackle these questions, however, I want to raise some broader issues that were provoked in my mind by watching the movie. For many years, I have been fascinated – and irritated – by the way in which highly dubious memoirs or testimonies by participants in intelligence scandals have been given an undeserved level of authoritativeness by being quoted by ‘serious’ historians. As examples, I offer four different accounts, one by an obvious scoundrel (Kim Philby), another by a fringe player of questionable integrity (Goronwy Rees), the third by an obsessive junior counter-intelligence officer (Peter Wright), and the fourth by a senior officer of good repute (Dick White). Their books (in White’s case, a biography to which he contributed) have been cited – usually carelessly – innumerable times, perhaps the most notable illustration being Christopher Andrew’s Defend the Realm. Thus the lies of those anxious to embellish their reputations become smoothly incorporated into historical lore. Level 1 – inaccurate history.

The next stage is when the events and characters are incorporated into fictional constructs – or that hybrid, fictional history. For example, John le Carré modelled Magus Pym (in A Perfect Spy) and Bill Haydon (in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy) on Philby. Alan Bennett wrote a couple of screenplays, A Question of Attribution (with Blunt as the lead character), and An Englishman Abroad (using Burgess), where the boundaries between historical fact and artistic invention were blurred, while he drew carefully-crafted moral or philosophical lessons from the dynamics and conflicts behind the events. Such works probably gained a much larger audience than those who studied any ‘historical’ volumes, yet most of them were written before the appearance of the authorized history, and had little access to relevant archival material. Level 2 – muddled realities.

A further level of sensationalism, or misrepresentation, may then occur when such works are reproduced in visual media – movies made for TV or for general distribution, where the potential audience is even greater, and the influence even more impressive. Call it the ‘I Claudius’ Syndrome. The opportunity for heightening the emotional or intellectual impact is maximal. (I have to admit that this is a medium that has largely passed me by. I am not a frequent movie-goer: the last movie I watched at the time of release was The Imitation Game, and this is partly why writing this analysis has been such a revelatory experience for me.) Yet it seems that the line between historical fact and artistic license is rarely clearly drawn (a reason why The Imitation Game irritated me), and viewers taken in by the extravaganza may end up with an even more distorted view of the facts behind the story. Level 3 – distortion and melodrama.

Friendship and Betrayal

Apart from an earnest inquiry as to what sociological phenomena caused the Cambridge Five to become traitors, I seem to recall that a prominent theme in works based on their exploits was the matter of betrayal itself, and the conflict between betrayal of one’s country and betraying one’s friends. That idea was frequently accompanied by the hoary statement from E. M. Forster about having to choose between the two, and his hope of ‘having the guts’ to betray his country, as if that provided some excuse for the treacherous behaviour of the Cambridge Spies. I have always regarded that as one of the most fatuous pronouncements of the 1930s (made in 1939) – as I shall explain soon – but I decided I should go back first to ‘What I Believe’ in Two Cheers for Democracy to verify exactly what Forster was trying to say.

It is not a very impressive paragraph, and Forster is shown to be making ‘friendship’ equivalent to some sort of comradeship towards a cause, and the famous quotation above is introduced with the phrase: “I hate the idea of causes, but . . .” It is utterly illogical. He has pointed out that ‘personal relations are despised today’ – a vapid, passive claim that cries out for some identification of who the ‘despisers’ are. Yet friendship is not inevitably tied to shared political fervour, and one might enjoy only superficial intimacy with colleagues who are dedicated to the same political cause. Moreover, if Forster hated causes, why would his friends have been those who went to (presumably) fascist or communist gatherings, or whatever was the 1939 version of CND or Extinction Rebellion? Surely he would have been closer to persons who, like him, were ill-disposed to the earnest demonstration of ideological commitment?

Nevertheless, the idea caught on. My own reaction has always been that, in committing to betraying one’s country to communism, if the objective were reached, one of the first human faculties to be eroded would be sentiment. The movement was everything, and personal relationships were subordinate. Come the Revolution, any weak-willed hesitant ex-devotee would be the first to receive the bullet. In the Soviet Union, in the 1930s, you had to get your denunciation in first, before your friend denounced you. And that might apply to family members, too: for instance, Molotov denounced and divorced his Jewish wife after Stalin had her arrested for ‘treason’. If such persons showed any sign of anti-Soviet thinking, and you did not declare them to be an Enemy of the People, then you were as guilty as they, and off to the Gulag you stumbled. So much for not betraying one’s friends. In A Chapter of Accidents Goronwy Rees claimed that he protested to Blunt along these lines after the latter tried to talk him out of going to MI5 just after Burgess and Maclean disappeared. The same essential message – that when you betray your country to totalitarianism you risk fracturing the loose arrangements that foster long-standing friendships – can also be found in Noel Annan’s Foreword to Robert Cecil’s A Divided Life.

This idea of friendship hardly pertains to the Cambridge Five, however. Cairncross was an outlier, and hardly knew the other four. Maclean was something of a loner, and did not mix closely with the other three. Philby was inscrutable, and actually seduced the wives of his friends. Blunt and Burgess enjoyed a special kind of friendship, a homosexual relationship. Burgess, ‘The Spy Who Knew Everyone’ in the words of Hulbert and Purvis, may have been a sparkling conversationalist, but his predatory and louche behaviour alienated many acquaintances. Moreover, at one critical juncture, he wanted one of his special friends, Rees, murdered, lest he betray the group. That constituted a weird kind of loyalty, in which the cause dominates over friendship, and it undermines the whole notion, especially when Burgess is later shown to be applying emotional pressure to Rees.

As for the causes of the Cambridge Five’s betrayal of the nation to the communist movement, much nonsense has been written about the subject, from Andrew Boyle to Richard Davenport-Hines. It was a revolt against the Great Depression, it was their public-school upbringing that led them into deceit, it was a missing father (or perhaps a dominant father), it was disgust over the privileges of their class (or a dismay that those privileges were disappearing), it was the arrogance of Empire (or the loss of Empire), it was their homosexuality (or bisexuality, or frustrated heterosexuality), etc. etc. What is absurd about any such analysis is that hundreds, maybe thousands, of young men coming from a very similar background never felt the urge to endorse Stalin and become spies, but instead ended up perhaps as rather ineffectual servants of the Crown, or else straightforward citizens who got on with their lives, and maybe sacrificed those lives in World War II for a better cause.

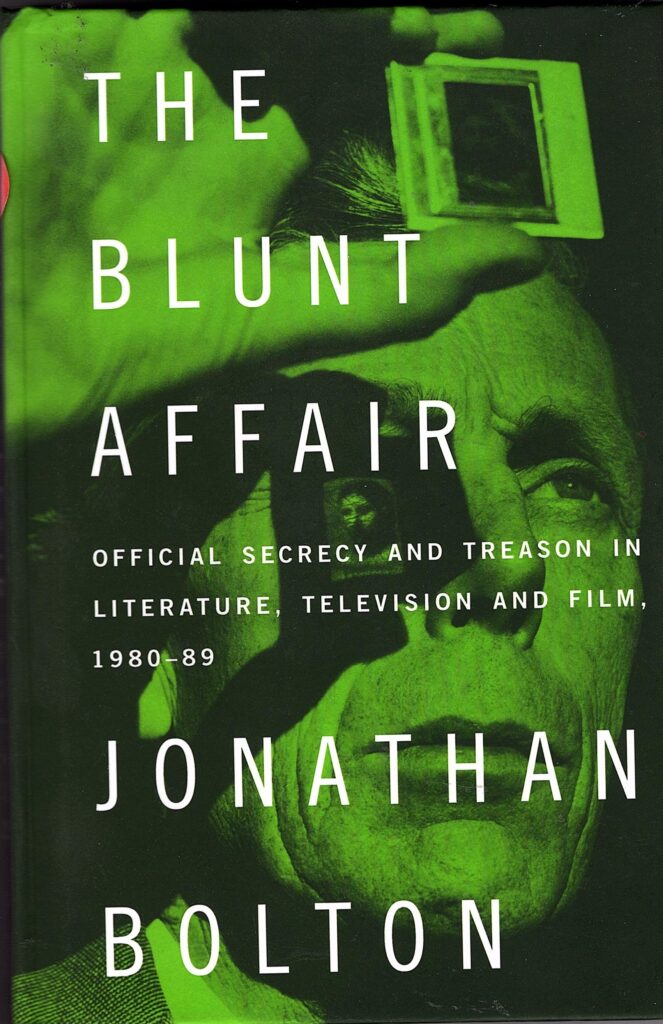

And then, just after I had viewed The Fourth Man for the first time, I discovered that someone had written about these matters. At great expense, I acquired The Blunt Affair, by Jonathan Bolton, published in 2020. It is subtitled ‘Official Secrecy and Treason in Literature, Television and Film, 1980-1989.’ Bolton is the Hollifield Professor of English Literature at Auburn University in Alabama.

‘The Blunt Affair’

The fact that it is the immunity granted to Blunt, and kept secret for sixteen years, that dominates Bolton’s thesis, is revealing. The author attempts to use it as anchor for his analysis of several works of drama, fiction and film, from Dennis Potter to the movie Scandal, but flails around trying to find a convincing theme of any substance. Moreover, his text is replete with such banalities, misunderstandings, non sequiturs, and sociological jargon that this reader strained to make sense of it all. The book has been atrociously edited: for example, Bolton writes ‘Education Rita’, and ‘Citizen Cane’, and introduces the biographer of Blunt as ‘Miranda Martin’, perhaps confusing her with the elegant TW3 chanteuse Millicent Carter. Practically every time he introduces a historical episode, he gets several facts wrong.

His unifying idea appears to be that those writers who studied the Blunt affair, and the shenanigans of the Cambridge Five, were essentially protesting about the evils of the Thatcher era – namely monetarism, inequality, greed, the rapacity of the free market, bigotry against homosexuals, government secrecy, abuse of privilege, military aggression (the Falklands), etc. etc., and that they were offering a necessary challenge to outdated notions of patriotism and privilege. Somehow, the subjects, primarily active in the 1930s and 1940s, ‘exemplified modes of anti-establishment thought and action during the late Cold War era.’ What the authors, whose works range from Tom Stoppard’s farcical The Dog It Was That Died to Joe Boyd’s and Michael Thomas’s 1989 movie about the Profumo Affair (Scandal) think (or would have thought) about such assertions is not clear. I do not believe that Dennis Potter was familiar with that entity known as ‘the LGBTQ+ community’.

One of the problems is that Bolton, in trying to harness these works to his theme, unwittingly displays a number of paradoxes and contradictions in his text. For example, he blames the Tory government for granting Blunt his immunity, but then has to accept that Douglas-Home and his successors were not told of the MI5 initiative, and that it was in fact Thatcher herself who brought the case into the open. He continually adopts the voguish meme of criticizing ‘late-stage capitalism’, but he then has to point out that that system helped bring about the fall of communism in 1989. He frequently draws attention to the existence of bigotry against homosexuals within the Establishment, but then reminds us that it was the clannishness of the Foreign Office and MI5 that ignored the sexual preferences of Burgess and Blunt. He praises the authors of the works for their reliance on biography and memoir [sic!] for their factual accounts, as opposed to the melodrama of the tabloid media and the unreliability of official statements, but then points out that The Fourth Man was heavily criticized for the liberties it took with the truth. National Service was an unjust penance, and an infringement of personal rights: but those who were exempted from it felt excluded. Etc. etc.

This is all shrouded in verbosity (‘heteronormativity’, ‘the reality of reality’) and repetitiveness. Several times he invokes, and re-quotes, the Forster statement, without inspecting it closely (although he does credit the speech given to Rees in One of Us that pulls it to pieces). And behind it all is the constant theorizing about what drove the spies to their treachery, displaying a complete lack of insight concerning social causes that I highlighted beforehand. One can find a few valuable comments about the art of composition and the representation of character in the works, but overall the book is a mishmash, and should never have been published, to my mind.

I offer an example of the Professor’s style, a passage that he presents when he tries to sum up his argument:

As Russian operatives continue to interfere with the liberties of Western democracies, as late-capitalism mutates into corporatocracy, oligarchy and kleptocracy, producing precisely the kinds of economic inequality that the Cambridge spies found repellent, as national ideologies demand patriotic fidelity in order to enforce territorial boundaries and preserve misguided notions of ethnic homogeneity, and as powerful forces of religious orthodoxy foster a bigotry that challenges equal rights in the LGBTQ community, many should find the texts considered in this study to retain the value and relevance that they held back in the 1980s, and also find that they reward thoughtful reading and viewing.

If you enjoy sentences like that, this is a book for you. But I think the Professor should have gone back to an undergraduate class.

‘The Fourth Man’: The Storyline

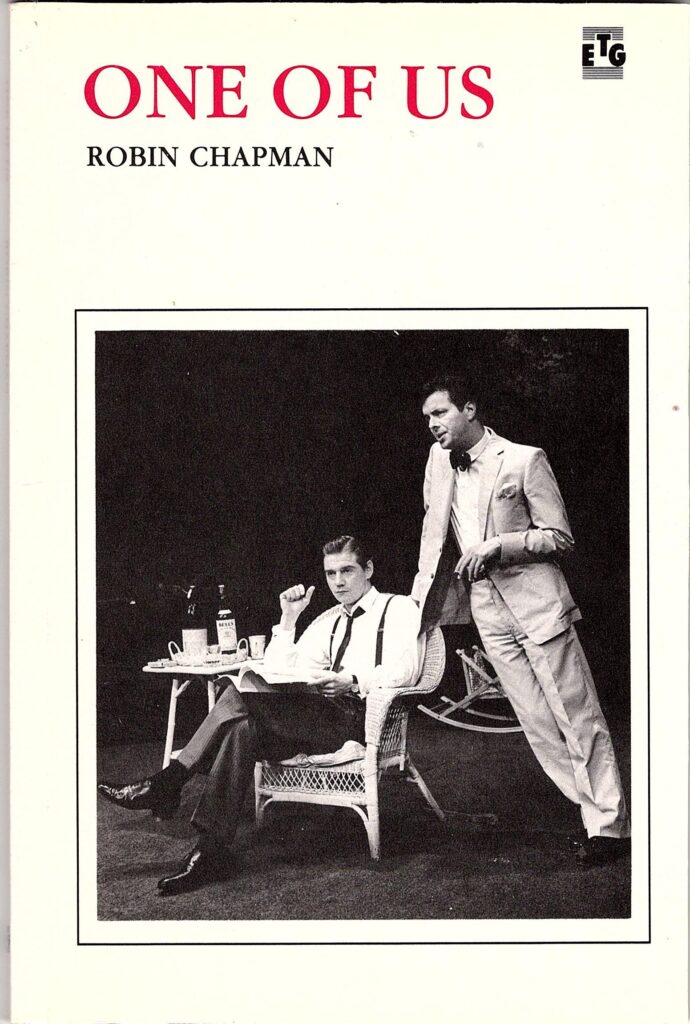

The movie’s screenwriter was Robin Chapman, and the script was based on his two-act play titled One of Us, which enjoyed its first performance at the Greenwich Theatre, London, on February 12, 1986. The action of that drama takes place at the home of Goronwy and Margaret Rees, the first act on May 6, when Guy Burgess visits them, fresh from his return from the USA, scene one of the second act at night on May 27, two days after Burgess and Maclean fled, and scene two the following morning, when Anthony Blunt comes to talk to Goronwy. The author describes the play as ‘a work of the imagination based on fact’, and describes the hypothesis from which the action evolves, namely that Blunt recalled Burgess from the United States, as his own ‘imaginative but reasonable assumption drawn from the historical facts as they are currently known’.

The essence of the plot of One of Us can be told quite simply: Burgess visits Rees to explain the imminent escape of Maclean to Moscow, and Blunt’s role in it, and he manages to persuade Rees to promise that he will not betray him and Blunt as they prepare for the departure. Three weeks later, after Burgess signals his imminent departure to Margie over the telephone, Rees admits to his wife his past involvement with the Comintern. Shocked, she tries to convince him to have nothing more to do with Blunt, who has been pestering her by trying to call her on the phone while her husband has been away. When Blunt arrives the next morning, he reminds Rees that, if he denounces Burgess, the spotlight will be placed on his own shady past, and he emphasizes to him the necessity of being loyal to his friends first. Rees vehemently complains that Blunt is distorting the famous statement that E. M. Forster made about the betrayal of friends and country, and ripostes that he has other friends and family dearer to him than utopian comrades. Rees sends Blunt packing, and he tells his wife that he will indeed contact MI5.

There are some clever exchanges in the dialogue, although it is not clear exactly why Burgess sought out Rees so eagerly, and the role of Blunt as super-fixer of the whole operation is undermined by how Blunt himself describes his contribution. Burgess is the most colourfully drawn character, and is given an outrageously camp flow of language that would seem offensive today. Rees is shown as weak, and his much younger wife appears as a strong and imaginative foil to her vacillating husband. The play ends with Rees apparently set on telling MI5 all he knows, although he expects that he may end up feeling like a traitor.

When One of Us was transformed to the screen, several changes were made. The main thrust is that the attention switches sharply to Blunt, and his machinations behind the scenes. The freer format of film allows some events hinted at in the stage play to be delivered directly, and some new action to be created that sometimes illuminates but frequently undermines the essence of the story. Moreover, whereas the play ends with Rees’s apparent determination to tell MI5 all, the screenplay adds a substantial twist to the plot.

The main action starts with Blunt meeting his Soviet contact, Vasily, in a Gentlemen’s Public Convenience in early May, where, after Blunt reminds Vasily that it was he himself who recommended Burgess’s recall, Vasily informs him that Burgess has just arrived. Blunt is very much in charge, and rebukes Vasily for arranging to meet in such an exposed and dangerous place. (In this scenario, of course, with Blunt taking the initiative, and engaging Philby’s help, he would really have been the ‘Third Man’, with Philby related to the ‘Fourth Man’, but history had taken its course by then!) The next scene shows Burgess arriving at Blunt’s apartment at the Courtauld, and, after a loving reunion, Burgess explains how the CIA had forced Kim Philby’s hand, whereupon Philby had confused the issue in order to give his comrades time to prepare. Burgess claims that his speeding offenses were designed to make the Embassy send him back to the UK on the first boat home. Blunt explains that Burgess’s role is simply to ‘nanny’ the very distraught Maclean and get him out of the country. Maclean’s distress is shown when he and Burgess call Blunt from a public telephone box.

Blunt is then shown at a meeting with Guy Liddell of MI5, where he receives an update from the Assistant-Director on narrowing down the list of ‘HOMER’ suspects to four, one of whom is Maclean. The date is May 16. Blunt informs Liddell that Guy ‘sends his love’, and he tells him that Burgess has just gone to Sonning to visit Goronwy Rees. The action shifts to Sonning, where Burgess is ingratiating himself with the Rees family, although there is obvious tension between him and Margaret Rees. Privately, Burgess updates Rees on the HOMER business, and on Maclean’s achievements in purloining valuable atomic secrets, all the time subtly suggesting that Rees is as much a conspirator as the others. While Goronwy is on the telephone, Margaret asks Guy about the man in the club who had accosted her husband the previous November, and who had accused him of ‘ratting’. (It was Donald Maclean, but Burgess does not have time to reply to her.) Guy and Goronwy then have another serious discussion á deux, where Guy informs Goronwy of the plan for him to accompany Donald for the first part of his escape. He again reminds Goronwy that he is ‘one of us’, and he is able to extract from him a promise not to tell anyone – even Margie – about the machinations and connections. Rees, biting his lip, agrees to remain silent, as a friend, in order to protect Blunt.

Blunt is then seen entering Clifford Chambers, where Burgess has his flat. Finding Guy in bed with his friend picked up on the Queen Mary, he urgently extracts him, since he has learned that Maclean’s interrogation is planned for May 28. Blunt gives Guy instructions for the escape, handing him travel tickets, a visa (for Maclean), and cash. The plan is for Guy to accompany Donald as far as Paris, with instructions for Maclean to move on to Prague, while Guy will return home, all innocent, explaining that his friend gave him the slip. Guy will rent a car and pick Donald up at Tatsfield for the journey to Southampton, and then St. Malo. Burgess reminds Blunt that Kim’s last words to him were: “Don’t you go, too!”. Anthony and Guy plan to meet up again on Tuesday May 29. Burgess looks very thoughtful, as if considering the enormity of what is about to happen.

Guy is then shown calling the Reeses very ostentatiously from the Reform Club, finding Margie in (he knows Goronwy is in Oxford that weekend). He informs her in a drunken and incoherent state that he is about to do something astonishing, and will be away for a while, and reminds her that her husband must ‘do the right thing’. Blunt is then shown meeting Vasily at the more sensible Treffpunkt of Kew Gardens, where he again shows who is boss. He tells Vasily of the plans, and he instructs him that his bosses must take over when Maclean arrives in Paris.

The date is now Friday May 25. Maclean is tailed to Charing Cross station, at which point his watchers sign off for the day. Driving down to Tatsfield in a cheerful frame of mind, Burgess posts a letter to Blunt, confident, after he engages with the collector in banter, that it will be picked up that evening. The next morning, Blunt receives the letter, on Reform Club notepaper, which contains the simple message: ‘What’s Become of Waring?’. He looks up the text of the Browning poem, and quickly concludes that it is a coded message informing him that Guy is not planning to return. He thus hurries to Burgess’s flat (where Guy’s boyfriend Hewit is fortunately not at home), raids Guy’s private boxes and drawers to retrieve incriminating letters, film, photographs and documents, and takes them in bags to the furnace at the Courtauld Institute, where he incinerates them. One last item visible is Guy’s 1951 Communist Party membership card.

A short scene then shows Blunt trying to call the Reeses on the phone, with Blunt hanging up when Margie picks up. (Goronwy is still in Oxford.) Rees arrives home, and Margie tells him of Guy’s incoherent call, and then of the repeated hang-ups. She wants to know what is going on, and she is not convinced by Rees’s feeble attempt to explain that Guy was talking about his new job. Margie is suspicious – and maybe jealous – of her husband’s close friendship with Guy, and challenges him by saying that Guy perhaps means more to him than do his wife and children. Goronwy is torn between his promise, and what he owes his wife, and tries to explain it away by saying that Guy was a spy for the Comintern, and that he had tried to enroll him in it as well. That leads Margie to suggest that Rees had also been a spy, and she asks whether Maclean’s outburst at the Gargoyle Club was related to Goronwy’s previous affiliation. He struggles to explain: Margie cannot understand why Rees would not go to the authorities when he learned that Guy was still spying, and Goronwy resorts to the theme of not betraying one’s friend.

After a brief telephone call that Margie picks up, the caller (Blunt) simply identifying himself as ‘a friend’, Blunt tells Rees that he needs to see him urgently the next day (Monday). On hearing this, Margie asks whether Blunt is a spy too, as she recalls the flat in Mayfair where Rees, Blunt and Burgess met during the war. It is here that Rees shares his belief that Burgess has gone to Moscow: he does not know what to do, as he admits to Margie his low self-esteem. They argue: Margie does not want her husband to meet with Blunt, but he convinces her that he may be making too hasty a judgment about the flight to Moscow, and ought to listen to what Blunt will tell him. Reluctantly, she tells him that he must do what he thinks best.

Blunt visits Rees in Sonning: neither is in a good mood. Rees tells Blunt all he knows, somewhat to Blunt’s surprise. Rees admits that he told his wife the whole story, which shocks Anthony. Blunt then astounds Rees by telling him that he knows that Rees contacted David Footman of MI6 the previous evening, a nugget he had acquired from his friend Guy Liddell. He admits to making the anonymous phone calls that Margie picked up. While admitting that his fate is essentially in the hands of Goronwy and Margie, Blunt strenuously reminds Rees of his necessary loyalty to his friend, citing Forster again, and points out that the authorities will be very suspicious of Rees’s testimony, anxious to know why he had taken so long to inform them of his friends’ treachery. There is a hint that Rees’s absence in Oxford during the weekend of the escape was not purely coincidental. For the first time, Rees responds with appropriate passion, and stresses to Blunt that he has made up his mind to tell MI5 all. “On your own head be it!”, responds Blunt, and leaves.

Liddell has invited Rees to his club for luncheon, so that they might there discuss Rees’s concerns. Rees is surprised at the venue, and its lack of privacy. He is even more astonished when Blunt turns up as the second guest. It must be June 1, as Goronwy states that the Burgess phone call happened six days beforehand. Rees is set back considerably by the fact that Liddell and Blunt appear to be in complete sympathy as they encourage him to speak up. Liddell explains what little they know so far about the abscondment of the pair, but he does not appear to be greatly alarmed. Rees is stunned into silence by the conspiratorial nature of the spy and the counter-espionage officer.

A brief scene shows Blunt and Vasily meeting again. Blunt declines an order to escape to Moscow himself, reminding Vasily of his prominent position and reputation, indicating he is untouchable. It is the day that the ‘Missing Diplomats’ story broke – June 6. Lastly, Rees has a meeting in Liddell’s office, with Dick White in attendance. Again, Liddell does not appear concerned. Rees asks him when he is going to haul in Blunt for questioning, but Liddell indicates that he will mull on it, and keep a close eye on the former MI5 officer. And at that point the movie ends.

Neither One of Us nor The Fourth Man could be said to be didactic, but the lesson has changed in the transfer from the stage to the screen. In One of Us, Rees appears to come to a belated conclusion that the loyalty that he owes his wife and his country is more important than a promise he has made to his friends (and conspirators) that he will not betray their secret, and he prepares to undergo what may turn out to be a difficult conversation with MI5 with a degree of confidence that he will be able to overcome their suspicions, and explain away his tardiness. The Forster assertion gets its come-uppance.

The situation has become much more nuanced by the time that The Fourth Man is delivered. The same demands of personal friendship are emphasized by Burgess and Blunt, and Rees’s weaknesses are again exposed, but the denouement presents a shocking climax for Rees. The fact that Blunt has insinuated himself into Liddell’s confidence, and has succeeded in lining him up as an ally against Rees, presents Goronwy with a more alarming fact – that a personal and institutional loyalty between Liddell and Blunt has perverted the cause of justice, and made the question of betrayal of country or friend almost irrelevant. The fact that Rees’s prolonged silence is shown to be held against him reinforces the point that Rees has betrayed himself, by not coming to grips with reality early enough, by not facing up to the conflict in loyalties when it first occurred, and by not understanding what the bonds of love and marital faithfulness should mean in practice. Yet the relationship between Blunt and Liddell is left enigmatic: is it just a misreading of collegiality, or is there something more sinister afoot?

The Sources

What was available to Chapman when he wrote his works? Chapman had written about ‘the historical facts as they are currently known’, but he had a welter of ‘facts’ to select from. The published material available in 1987 consisted of a mixture of evasive official statements, unconfirmed press reports and rumours, leaked propaganda from ministerial offices, exculpatory tales from friends and family, mendacious memoirs designed to protect reputations, some probably accurate insights from intelligence insiders disgruntled about the cover-up, and misleading stories from participants planted to lay a false trail. Amid all this lay a host of contradictions that any person who was trying to transform the events into a dramatic work would have to pick from very selectively. One might assume that Chapman read all – or most of – the relevant literature: in any case, he encountered that pitfall of selection.

The first work to appear was Cyril Connolly’s The Missing Diplomats (1952), who exploited the fact that he had met Maclean socially in the two weeks before the escape to inform his readers that Burgess had bought the tickets on Wednesday 26 May, that Maclean was calm at lunchtime on the Friday he left, and that Burgess had his last drink in London that day at 7 o’clock. He also stated that the details of the journey from Rennes to Paris had been established.

A couple of years later, Geoffrey Hoare offered his insights, in The Missing Macleans (1954). Hoare was married to the notable journalist Clare Hollingsworth, and was on close terms with Donald’s mother-in-law, who had married Charles Dunbar after gaining a divorce from Melinda Marling’s father. Hoare wrote that Donald had told Melinda on May 24 that ‘Roger Styles’ would be coming to dinner the following evening, although he asserted that Burgess did not book the two berths until the day of departure. Nevertheless, Hoare discounted the theory that a sudden warning precipitated the flight, and he suggested that Maclean had dropped broad hints to Melinda that he would be leaving. He expressed the opinion that neither Burgess nor Maclean believed that he would never return to Britain, but indicated that Moscow decided that it would be too risky to allow Burgess to return from accompanying Maclean to Paris, and ordered his flight, too. Hoare mentioned the very flamboyant way in which the pair drew attention to the details of their flight.

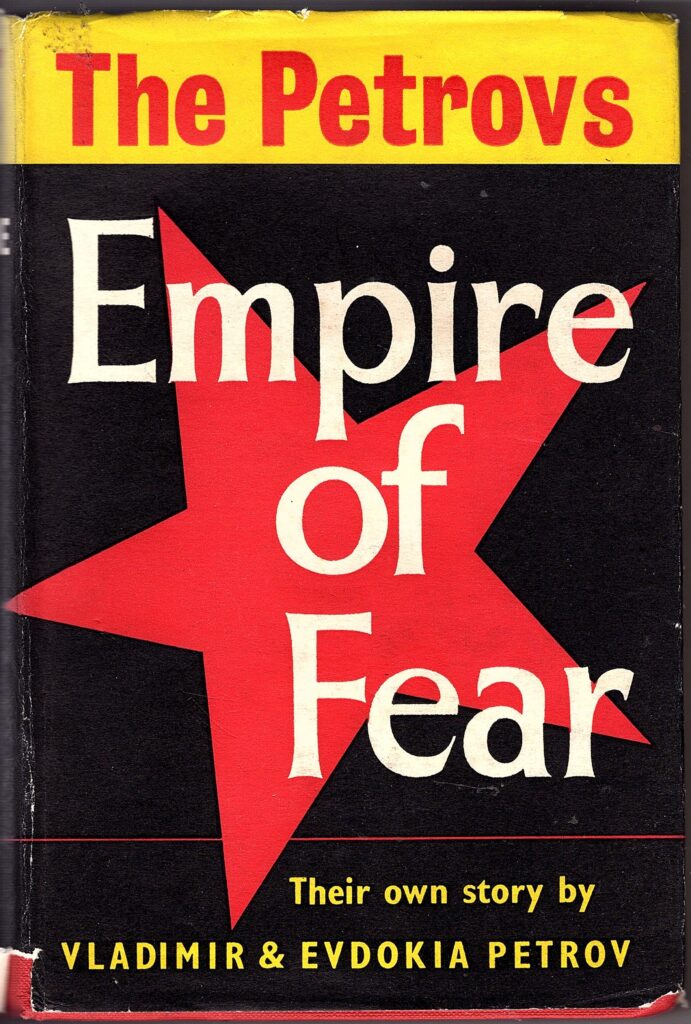

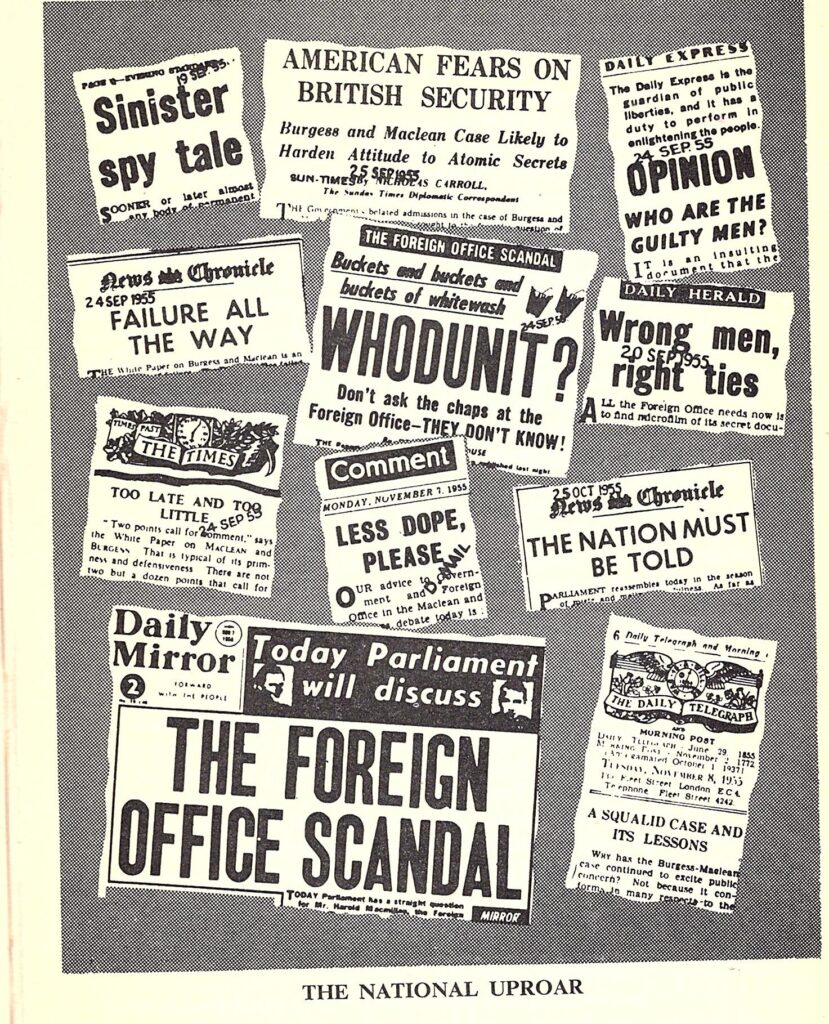

Input from an unexpected quarter arrived when Empire of Fear, the ghost-written memoir of the defectors in Australia, Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov, was published in 1954. This was of importance, because Petrov’s MVD boss in Australia had been Kislitsyn, who had helped plan and direct the escape of Burgess and Maclean. (Kislitsyn had been in London between 1945 and 1948.) He stated that the plan was initiated because both of the spies were under investigation, and that they had reported the surveillance with some alarm to their Soviet handlers. Many plans were apparently put forward (and rejected – suggesting that the process took several weeks) before the final project involving an eventual air flight to Prague was approved. Petrov did not know how the couple reached Paris, but he was confident that Donald confided in Melinda before he left. [Melinda eventually escaped to Moscow, with her three children, in 1953.] Kislitsyn intriguingly suggested that Burgess and Maclean did not know each other as agents before the emergency. Robert Manne expanded slightly on this account in his 1987 book The Petrov Affair (which probably arrived too late for Chapman), in which he confirmed that Kislitsyn aided the escape working under Raina and Gorsky (the wartime minder of the London-based spies), adding that Petrov did not know the identity of the ‘Third Man’, but thereby confirming the role of an abettor. He opined that some London newspapers gained their stories from disgruntled MI5 officers disillusioned with their institution’s incompetence over the affair. He refers to a Times editorial ‘Too Little, Too Late’ from September 24, 1955, that I have not been able to locate.

An official statement, given under much pressure, was released on September 23, 1955. Titled ‘Home Office Report on Missing Diplomats’, it was compiled by the MI5 officer Graham Mitchell under the guidance of Dick White. Analysts such as Nigel West have criticized it for its many errors, but the report contained a few salient observations. It set out by claiming that Foreign Secretary Morrison had on May 25 indeed approved the proposal to interrogate Maclean, but that the interview had been delayed until mid-June (i.e. after Melinda’s confinement). [West lists this as an untruth, but in this case West was certainly wrong.] Thereafter, what Mitchell had to offer was bland: he indicated that Maclean knew he was under investigation (excluding Burgess implicitly), and then he related some of the details of the passage, and Melinda’s reporting her husband’s absence to the Foreign Office on the afternoon of Monday 28 May. He refers to the telegrams – both fake and real – that arrived from the two spies and, rather lamely, reproduces the evidence that the Petrovs had presented. It is not a very convincing or illuminating report, but it does contain some reckless language that embarrassed the government later. In Section 11, it states that Maclean ‘may have been warned’, and in Section 26 affirms that suspicion: “In the event he was alerted and fled the country together with Burgess.” Those statements would dramatically introduce the ‘Third Man’ controversy.

A compilation of mainly press reports, augmented by interviews with insiders, appeared as The Great Spy Scandal, which was published in 1955, with Donald Seaman and John S. Mather as the authors. It is for that reason not a very coherent account, but it does introduce several telling items. One of the first is the information that Burgess told his live-in boyfriend, Jackie Hewit, soon after he arrived back in Britain that he had a ‘friend in trouble’ whom he needed to help – surely a very incautious move. The authors add that Hewit and Miller (Burgess’s alleged pick-up from the Queen Mary) did not report that Guy was missing until Monday May 28. Hewit then called Blunt to let him know (on the authors’ assumption that Blunt knew nothing), and Blunt then contacted the authorities. As for Maclean, he apparently told his Hungarian contact (Ludwik Frejka, who was hanged in 1952) that he had taken Melinda into his confidence, and the story echoes the claim made elsewhere that both Burgess and Maclean noted that they were under surveillance. It may have been Hoskins of the Daily Express who aired the rumour that there was a ‘Third Man’ who alerted Burgess and Maclean of the imminent danger. Hoskins (perhaps receiving a dubious tip from inside the Foreign Office) had claimed that the warning might have arrived from Washington or London. A last, rather mysterious, anecdote describes how Hewit reported that Burgess had received a troubling phone call from Maclean at 5:30 pm on May 25, and that Burgess seemed upset by it. Burgess of the News Chronicle asserted that MI5 knew about this warning. [The variously attributed movements of the evening of May 25 merit a complete separate analysis, since they take on an Agatha Christie-like complexity. The accounts given here, and by Fisher, and later by Cecil, are in such blatant contradiction that a detailed inspection of train timetables and the geography of north-east Surrey is essential.]

Guy Burgess also made a contribution when Tom Driberg visited him in Moscow. Guy Burgess: A Portrait, written by Driberg, and published in 1956, is predictably misleading. Burgess claimed that Maclean was the second person with whom he got in touch after arriving in England (after Blunt? Rees?). They met at the Reform Club, and Maclean told him that he was being tailed, possibly because of his pro-Soviet remarks, and let Guy know that he wanted to clear out and go to Moscow, seeking his friend’s help in getting tickets. A few days before they left, Burgess decided he wanted to accompany him, too – how far is not clear: he also told his interlocutor that Petrov’s account that the Russians planned it was ‘pure rubbish’. Burgess then contradicts himself: he says that he did not know that he was going the whole way to Moscow with Maclean until he got to Tatsfield. He added that Maclean acquired his Czech visa at the Czech Embassy in Berne, that Burgess reached Prague with Maclean, and that he ‘decided’ to accompany him to Moscow when the story broke. What happened with Burgess’s visa requirements was not stated, and how the two managed their negotiations with the Czech Embassy without Soviet help is not explained. It is difficult to take Burgess’ account seriously.

[In July 1963, Edward Heath, Lord Privy Seal, acknowledged to the House of Commons that Philby had indeed been the ‘Third Man’ who ‘had warned Maclean through Burgess that the security services were about to take action against him.’]

The famed author and journalist Rebecca West picked up the story in her New Meaning of Treason (1964). While she brought little fresh insight to the mechanics of the escape (and indeed misrepresented many aspects), her independence of mind and her sceptical intellectual analysis highlighted many of the paradoxes of the events. Her account of the circumstances of the escape is unfortunately riddled with vague and unattributed rumours. For instance, she declared that Maclean fled with Burgess when he had just been informed ‘probably by several persons, including another person in the employment of the Foreign Office named Philby, that he had been detected and was under surveillance by security’. She provocatively asserted (without providing a source) that Maclean had been identified as the principal suspect as early as 1949. She bizarrely deemed it probable that Philby told Burgess that Maclean was about to escape to the Soviet Union, and instructed Burgess that he must therefore accompany him.

West is stronger in describing the inexplicable poor performance of the security authorities in failing to prevent the defections, or manage the fallout: the absurd way in which the disreputable behaviour of Maclean and Burgess was rewarded with further employment; the clumsiness of the surveillance; the questionable role of Roger Makins in watching Maclean at work; the ridiculous suggestions that Burgess and Maclean made a decision to leave on learning of Herbert Morrison’s approval of the interrogation; the unnecessary alerting of the Sûreté; the behaviour of Melinda Maclean; the amateurish explanations that followed. She also drew attention to the flamboyant way that Burgess went about his preparations, including the very obvious (and unnecessary) hiring of a car to enable the escape, and the reckless dash to Southampton, the failure of which would really have set the cat among the pigeons.

For some reason, Dame Rebecca – perhaps because she was considered an outsider meddling in matters she did not understand – did not receive the recognition she deserved from other journalists. Her conclusion, however, when she assessed Philby’s quoted admission that he had warned Maclean through Burgess that the security services were to take action against him, summarized the general way in which the notion of the ‘Third Man’ has been allowed to be distorted: “It [the statement] does not explain why a Soviet agent in England, certainly in touch with local agents, could be warned that he was being watched by English security agents only by another Soviet agent in America who sent a third all the way to England to tell him so. Soviet intelligence has better communications than that. This cannot be the story.”

Indeed. In these sentences, however, West revealed her own confusion as well as hinting at the generic fog that the British government managed to spread over the whole business, a miasma that has never properly been dispelled.

Kim Philby put his oar in, in My Silent War (1968). Predictably, it moves Philby himself to the centre stage, suggesting that he despatched Burgess to London in order to brief his Soviet control on what was happening – a scenario highly improbable for many reasons. Burgess was then to follow Philby’s instructions and contact Maclean to put him in the picture: there is no mention of Blunt, of course. At the same time, Philby reported how concerned he was at the lack of urgency with which the case was progressing, and he informed his Soviet contact of his worries.

Philby’s influence is also visible in The Philby Conspiracy (1968), also released as The Spy Who Betrayed A Generation (1969), by Bruce Page, David Leitch, and Phillip Knightley. Again, it is Kim who is instrumental in using Guy to send the alarm to London, and to warn Donald. Yet the authors remark on Burgess’s very leisurely return to the UK. The next movements between Burgess and Maclean mirror Burgess’s account of the story, with Guy agreeing to join Maclean when the latter asks him to. They diverge on the matter of the Soviets’ planning the whole affair, however, claiming that the Russians wanted to organize an escape-route in order to motivate other spies, should the occasion require it. And here is the first major push for the theory of the ‘last-minute alert’ – the notion that the interrogation was scheduled to begin on May 28, and that only on the Friday, when that decision was made, did an insider manage to get the news to the pair, so that their escape could be accelerated. They claim that Burgess received that fateful message as early as 10:00 am on May 25, whereupon Burgess made the final arrangements, told Miller that their trip was probably off, ordered the rental car, said goodbye to Hewit, and went to pick up Maclean in Tatsfield. In this wild and woolly scenario (‘a mixture of careful planning and last-minute improvisation’) the authors speculate that Philby could have received a cable in Washington on the Thursday night, and that he could thereby have notified the Russians! It is all very fanciful and absurd.

Also in 1968 a work with a significant title, The Third Man, by E. H. Cookridge, appeared. Cookridge was the anglicized name of Edward Spiro, who had known Philby in Vienna in 1934. Rather oddly, he does not introduce the concept of the ‘third man’ until he describes Philby’s interrogations after June 1951, when he records that Philby knew that there was nothing to connect him with ‘the missing diplomats’ or to brand him as ‘the third man’. It is not until Cookridge covers the defector Petrov’s deposition, published by the Australian Royal Commission on September 18, 1955, that the theme becomes clear. Here (according to Cookridge) appeared the statement that Kislitysn (who worked for Petrov in Canberra) had told him that a ‘third man’ in Washington had informed Colonel Raina that Maclean was under investigation,. This ‘third man’ had (so Cookridge claimed) also warned Maclean by sending a friend to London, but Kislitsyn did not know the names of either the emissary or the ‘third man’ in Washington. This essence of this reference had apparently been picked up by Marcus Lipton, M.P., on October 25, 1955, when he asked a question about the ‘third man’ in the House of Commons. Yet Lipton failed to join the dots properly, or else had misunderstood the information given to him. Foreign Secretary Harold Macmillan acknowledged the possibility of a tip-off, and even reported that Philby had been first secretary at the British Embassy, but he did not explicitly endorse the concept of a ‘third man’. This was potentially an extremely important disclosure by Cookridge, but he was in one significant way quite wrong. (I shall pick up this story in March.)

Cookridge had obviously had access to some insider information, and displayed a fresh account of Maclean’s last known movements, but he erred over a few other aspects of the story. Very provocatively, he argued that Philby quickly concluded that both Burgess and Maclean had become liabilities, and that they both ‘had to disappear quickly’. He even postulated that, had Philby been as ruthless as his masters, he might have arranged the liquidation of his two accomplices. This scenario, where Philby feels safer with both taken out of the picture, is clearly in contradiction of the favoured alternative, in which Burgess’s disappearance would lead to Philby’s unmasking, as well. It obviously casts doubt on the famed but questionable claim that Philby’s last words to Burgess were ‘Don’t you go, too!”

The timeline for the journey to Southampton is even more hectic in Cookridge’s narrative. He has Burgess driving to his club in Pall Mall at 6:30 pm, where he made several phone calls, before returning to his flat to collect his suitcase, and then driving to Tatsfield, which he surely could not have reached before 8:30. He and Maclean did not leave until 10:15, Burgess having to travel for nearly ninety miles in less than an hour and a half. With the state of the roads, and several towns to cross, it simply does not compute. Cookridge acknowledges Maclean’s rather unorthodox request to have the Saturday off, but he has nothing to say about the planned interrogation. He does indicate that Melinda called the Foreign Office, in some despair, on the Monday morning, and again, specifically to Carey-Foster, in the afternoon.

Richard Deacon made only a brief comment on the business in his History of British Seret Service (1969, revised and updated in 1980), but managed to mangle the story completely. His account reads as follows: “Gradually the counter-espionage service built up their case against Maclean, yet even when convinced reluctantly that Maclean must be interrogated on the subject of leakages of information to the Russians, a dilatory Foreign Office decided he need not be questioned until the weekend was over. Thus was Philby able to warn Burgess and Burgess to persuade Maclean to escape with him via Southampton and Le Havre on a secret route which took both behind the Iron Curtain.” How Deacon came to those absurd conclusions is unfathomable: it cannot be attributable to mere laziness, as his book elsewhere shows some diligence.

Goronwy Rees’s A Chapter of Accidents was published in 1972, and it has obviously exerted a powerful influence on many authors, especially Chapman. For details of Rees’s account, I draw readers’ attention to my analysis of his mendacious memoir in my coldspur bulletin of last September (see https://coldspur.com/an-anxious-summer-for-rees-blunt/ ). Of course, the archival material that shows up Rees’s deceitful account was not available in 1987, so perhaps some researchers and authors could be forgiven for believing that this eminent person would be providing them with an accurate story of the events of May and June 1951.

John Fisher was Chief Diplomatic Correspondent at the Times, and presumably well connected. His 1977 account, Burgess and Maclean, shows signs of being fed apparently useful nuggets, but Fisher should perhaps have cast a little more suspicion on what he was told. His account is remarkable for referring to Anthony Blunt several times – at a time, of course, when Andrew Boyle was being fed rumours about him. He offers some revealing details about the movements of May 25, including the potentially useful information that Maclean was normally driven from Woldingham Station to his home in Tatsfield – not from Oxted Station, which is farther down the line, a journey that Melinda Maclean claimed her husband regularly took. (I know that latter route well: it would involve a steep and eminently avoidable drive home up Titsey Hill. Yet Oxted has the advantage of a fast train from Victoria, which Maclean could pick up at East Croydon if he left from Charing Cross.) His description of the plans made is a bit of a muddle: he points out that Burgess’s journey home was not executed in a hurry, since Guy took a holiday in New York along the way. It is Fisher who reveals the essence of the VENONA program that led to HOMER’s unveiling, and he makes the alarming comment that Philby had ‘all along’ been a double agent. Fisher was apparently convinced by someone that catching spies and then turning them into double agents was a reputable and successful practice. (See my recent commentary on that phenomenon at https://coldspur.com/2024-year-end-roundup/ .) As for Burgess’s actions, he asserts that Guy went to Rees’s house first, after landing, that the plans had been made by the Russians in New York, and that Burgess booked the cabin on the Falaise on May 23 (the Wednesday).

It is not clear where Fisher is simply regurgitating stories that had appeared before. He credits Burgess with some skillful bluff over communicating plans for dining with Blunt on May 28, believing that Burgess knew that he was not returning, and that he set out to save his own skin at the expense of Blunt – and maybe Philby, who accused Burgess of doing just that. Miller has been taken in by the story that Burgess may have been alerted by Philby that Maclean was about to be interrogated, but he does not explain how that happened. With wild speculation, he suggests that Philby ‘might have slipped a message to Burgess on Friday afternoon’. He also identifies a call that Burgess made to the USA on May 25, for which Hewit paid the bill. As for Hewit’s activities, Miller has him calling Rees and Blunt over the weekend, and he echoes the statement that Culme-Seymour (Maclean’s luncheon partner on Friday) made that Melinda had known for a long time that she would end up in Moscow. All in all, it is another less than rigorous analysis.

The rather excitable and impressionable Richard Deacon (Donald McCormick) re-appeared, offering some commentary in his controversial book The British Connection (1979), which was recalled for pulping because of the Peierls errors, accusations made by Deacon in the belief that Peierls was deceased. Deacon had been told that Philby was tipped off to defect in 1963 because the CIA was about to kill him. He also claims that an anonymous letter was sent to the US Embassy as late as May 24, in which the writer asserted that Maclean had expressed to him sympathy for patriots who chose voluntary exile (such as the journalist John Peet, whom Maclean admired). The document was not made available until 1977, through the US Freedom of Information Act. Why it was concealed, or whether it was some sort of forgery, is difficult to determine. Deacon also makes anonymous remarks about Blunt, and the boasts that the latter made about his aiding the USSR during the war, which are interesting as further clues, but published just before the official disclosures about Blunt’s career.

And then came Andrew Boyle’s Climate of Treason (1979), which led to the unmasking of Blunt. [The revised edition of 1980 named Blunt explicitly.] Boyle states that Burgess visited Rees the day after he arrived, namely on May 8. He adds that Burgess and Maclean met several times between May 10 and May 20, sometimes at the Foreign Office itself – a factoid that would encourage the dual surveillance story. Maclean seemed to have accepted that the game was up, and he awaited the roll-out of the escape plan, which Blunt, in his ‘confession’ to MI5, had said had been worked out by him and his Soviet control. Boyle’s description of the fateful day is like that of many others a bit frenetic. Morrison had authorized the interrogation for May 28 (an item of misinformation supplied by Carey-Foster, the FO Security officer), and it was a closely guarded secret, but some form of warning from Philby arrived on May 23 or May 24 (i.e. before the decision had been made.) Boyle names Blunt as the source who told Burgess of the May 28 interrogation: Burgess knew of the escape plan, but he had no intentions of going further than Southampton until he undertook the drive to Tatsfield, when he decided on the spur of the movement to join Maclean across the channel. Yet Boyle next concedes that the Russians had decided that Burgess should abscond, too, as they could not trust him to keep the secret if he returned. Boyle echoes the main parts of Rees’s story, saying, however, that the critical meeting between Liddell, Blunt and Rees did not take place until June 7. He also inserts the idea that Burgess and Blunt had been farsighted enough to spring-clean Burgess’s flat, but he does not indicate when that happened.

In 1963, Donald Sutherland had co-authored with Anthony Purdy a work titled Burgess and Maclean. Sutherland updated it in 1980, under the title The Fourth Man. Sutherland rejects a lot of the common Philby-inspired story of his own role, namely that Maclean made up his mind to leave, and that Philby agreed with his Soviet control that Burgess should be entrusted with arranging Maclean’s escape. Sutherland’s judgment is that the RIS (Russian Intelligence Service) was in charge, but that it was a botched job, ‘badly arranged by a man on his own and in a panic’. Nevertheless, Sutherland has also been taken in by the story that Philby was able to cable Burgess on the morning of May 25, with the text being relayed by telephone. Somehow, it was a pre-arranged message that Maclean would be interrogated on May 28. (He even claims that MI5 later found the cable in the flat – an extraordinary achievement if the text had actually been read out to Burgess.) Sutherland then simply echoes the conventional story about Burgess’s partly rushed exit from London, without attempting to disentangle the paradoxical timings. He echoes the thought that Burgess intended to return, but that the Russians thought otherwise. Sutherland’s final flourish? “Alarm bells should have rung on the morning of the interrogation”, showing how he had been successfully deluded.

Chapman Pincher’s Their Trade is Treachery (1981) also takes a predictable path. He attributes no urgency to Burgess’s return to the UK, but that it was at Guy’s request that Blunt met him at Southampton. Burgess then described the purpose of his voyage, and that it was he who knew how to get in touch with Modin, the MGB controller. The Soviets decided to use Burgess as an intermediary to Maclean, who agreed to go to Moscow only if Burgess accompanied him. Thereafter, Pincher gets sucked into the last-minute warning syndrome, except rather than Philby being the agent, it was more probably a penetration agent in MI5 – namely Roger Hollis! Pincher’s bête noire somehow had taken part in, or heard about, the Morrison meeting, and had managed to contact Burgess between 10 and 11 on the morning of May 25 to let him know about the Monday interrogation. According to Pincher, when Modin heard the news, his bosses decided to move immediately. As my sometime doctoral supervisor, Professor Glees, informed me once, Pincher admitted that he invented things from time to time, and this anecdote would appear to emanate from that same fertile imagination. Pincher does add that Modin ordered Blunt to defect as well, but the art expert declined. That was something Pincher probably got right.

In A Matter of Trust (1982), Nigel West adds to the confusion. He is of the school that asserts that the interrogation of Maclean was indeed scheduled for May 28, to the extent of claiming that MI5 lied to the FBI in stating that the interrogation had been delayed a fortnight. West also claims that Liddell was ‘aghast’ when Carey-Foster informed him of Maclean’s disappearance that day. (Since Carey-Foster had learned of Maclean’s absence from Melinda only that afternoon, the surprised reaction does not ring true if Maclean was due to have been called in that morning.) West also states that Burgess had never come under suspicion as being a Soviet spy. He does, however, offer the intelligence that Liddell turned to Blunt for help, and that Blunt accompanied a couple of watchers from B2a to Burgess’s flat, where Blunt was able to sweep up some letters before the MI5 team found them. That episode was of course after the escape.

An important contribution was made by the Foreign Office insider Robert Cecil in his contributing essay to The Missing Dimension, edited by Christopher Andrew and David Dilks (1984). It was titled The Cambridge Comintern, and represents an interesting segue from what was largely gossip up to this time to the more formal and academic histories that followed in the next two decades. Cecil had known Maclean well, and he was appointed to replace him after the defection. His essay is an excellent tour d’horizon of the careers of the prime Cambridge Four, but it also reveals how susceptible the most expert witness can be to the attempts of those he respects to mislead. He is also a little imprecise in his chronology.

Cecil appears to trust what Goronwy Rees rote about his separation from Burgess and Blunt, although he claims that Rees gave an undertaking not to betray either of them back in 1939, which goes against the grain of how Rees represented his view of Blunt’s allegiance. He accepts Philby’s highly improbable divorce from Litzi without question. He implies that Maclean was still in touch with his control right up to the time of his surveillance, but he offers no evidence for that assertion. He rightly does not believe that the incidents of Burgess’s speeding in Virginia were part of any ruse to gain Burgess’s departure: instead he judges that Phiby exploited his expulsion in an ‘unprofitable’ venture to use him as a go-between. Yet Cecil was taken in by the claims of his Foreign Office colleagues that Maclean was going to be brought in on May 28, and that there was some kind of ‘Third Man’ who tipped the pair off. He even criticizes MI6 for not accepting that Philby was the ‘Third Man’, but does not explain whether, by this, he means the officer who raised the alarm in Washington, or the man who passed on the (false) secret about the imminent interrogation. He presents the American student Miller as Burgess’s ‘boyfriend’, which he clearly was not: he declares, without evidence, that Burgess was not under surveillance, which probably reflects what another inside told him. Finally, in what became a more controversial item, he criticizes Roger Makins (the Deputy Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office) for not passing on to Carey-Foster, its Security Officer, the fact that Maclean had asked for leave of absence for the morning of Saturday, May 26.

Chapman Pincher followed up his earlier work with his mammoth Too Secret Too Long (1984). He dedicated a chapter to the defections, which is replete with much earnest speculation, a lot of imprecise dating, and multiple insights granted to him confidentially, all of which he implicitly trusts. What truths he may have gathered in his investigations are swamped by the numerous hypothetical events he posits. Thus he confidently assumes that Philby accepted that, when Oldfield told him in September 1949 about the leakage from the British Embassy, the culprit was Maclean. Thereafter, Pincher relies too much on what the FBI agent Robert Lamphere told him, for instance that the FBI was not even told that Maclean was a suspect until after he and Burgess had absconded. He also cites Blunt’s various ‘confessions’, sometimes as ‘confidential information’, such as the claim Blunt made that Philby had managed to warn Maclean when he was in Cairo, and thus contributed to Maclean’s breakdown before he was recalled in May 1950. This might be a very important insight, but it is hardly verifiable.

Another confidence entrusted to Pincher was the claim that Burgess was under similar suspicion before he went to Washington in August 1950 and that, ‘organized by MI5 or MI6’, an army officer was sent out to keep an eye on him. He carries on in this vein, with stories about Maclean possibly having have met his Soviet controllers around Tatsfield just before he absconded, since he was not being surveilled in the country. Without giving any dates, Pincher declares that the KGB plotted Maclean’s escape in Moscow, and selected Burgess to warn him. Despite characterizing Burgess as being in addicted to drugs and alcohol at this time, the KGB also believed that Burgess was a suitable companion to prevent Maclean from getting drunk and distracted in France during the escape. Yet elsewhere he echoes Blunt’s claim that the Soviets had decided some time before that Burgess had to be part of the package. He mysteriously treats Burgess’s booking of the berths on the Falaise as a ‘coincidence’. With Pincher, all roads lead to Roger Hollis, of course, and so, while correctly rubbishing the theory that Philby could have had the time to warn his colleagues of the imminent interrogation, he assures his readers that it was Hollis who, as Security Officer for MI5, managed to get a message to Burgess on May 25 to accelerate the departure. Hollis’s role was, naturally, covered up. Enough said: it is a typical Pincherian muddle and bluster, all delivered with the confidence of the insider with connections.

The penultimate relevant work, which may have arrived too late for Chapman’s consideration, but is worth including for the record, is Conspiracy of Silence (1986-87), by Barrie Penrose and Simon Freeman. It is, like so many of the other accounts, much of a muddle, but it does shed fresh light on the supposed actions of Jackie Hewit and Goronwy Rees. Their narrative follows closely the notion of Philby’s propulsion of the plan, even to the extent of Kim’s ability to alert the duo to the need to escape at the last moment, despite his remoteness in Washington. The timetable indicates that Burgess was met by Blunt at Southampton, and proceeded to Sonning the next day, suggesting that Rees in some respect had an important role to play. The authors even make the provocative claim that Hewit had declared that Rees was ‘up to his neck’ in the whole business, was panicking, and that Burgess went to Sonning to re-assure him. That would shed a completely fresh light on the relationship between Blunt and Rees, if true, but would seem to fail the test of a realistic chronology. How would Burgess have known, from the USA, that Rees was already panicking?

Thereafter, their account follows the line that Maclean, in a state of nervous collapse, asked Guy for help in getting to the Soviet Union, Hewit offering the opinion that he would not go unless Burgess accompanied him. As for the circumstances of the fateful weekend, Penrose and Freeman indicate that Rees called both Footman and Blunt on the Sunday night, and that Hewit also called Rees and Blunt because of Burgess’s extended absence. They roughly follow Rees’s version of events, but they claim that Rees was so frightened by his own entanglement that he created a cover-story to implicate Blunt. They echo the story of the searching of the flat (on May 29), claiming that Rosamund Lehmann told them that Rees had helped Blunt on that project. Lehmann also believed that Rees knew a lot more about what was going on than he admitted.

I include here as the last book to be analyzed Nigel West’s Molehunt (1987), since, even though it was also too late to have been considered by Chapman, it seems to me to belong to the more novelistic approaches of the 1980s. West endows his description of the events with some flourishes probably intended to apply verisimilitude, but which serve only to undermine his authority. Thus his Introduction describes Maclean as ‘a well-dressed young man’ (it was his thirty-eighth birthday) ‘driving through the country lanes of rural Kent’ (both Oxted and Tatsfield are in Surrey), after which he ‘swung through the gates of a modest, two-story home’ (it was hardly modest, containing four bedrooms, but, if it had been, it would probably not have had gates). He goes on to write that Maclean had ‘caught his usual commuter train, the 5:19 from Charing Cross to Sevenoaks’ (it was the regular 6:10 from Victoria to Oxted). Without specifying any times, he then writes that ‘Roger Styles’ (Burgess) arrived about half an hour later (6:30 pm?), and that the Macleans and Burgess sat down to a meal at 7, after which Burgess and Maclean drove away in Burgess’s cream Austin A40 at about nine o’clock. How, if the escape had been a ‘last-minute affair’, arrangements were set up in France for them to proceed to Moscow, is not investigated by the author.

West’s tale then becomes a bit more interesting, yet still problematical. Melinda and Donald apparently maintained a pretense that she had never met Burgess, the purpose of whose visit was ‘to enable him to escape abroad’. Since Burgess had just been tipped off that the Foreign Secretary had that same morning consented that Maclean should be interrogated the following Monday, Burgess’s task that evening was to ‘persuade Maclean to flee, while taking precautions to being identified as a fellow-conspirator’. That was, to say the least, leaving the appeal a little late. Yet Donald and Melinda knew that their house had been bugged, and that all their conversations were being recorded even when the headset was not in use. MI5’s case officers had no idea that their project had been compromised. The play-acting in which the trio indulged was ‘just one of the countermeasures devised by Burgess to throw MI5 off the scent’. (Whether MI5 had picked up anything useful before Burgess’s arrival is not considered by West.) West observes that it was not until the afternoon of May 28 that Melinda telephoned the Foreign Office to report that her husband had disappeared. Presumably the interrogation team was sitting at Leconfield House just twiddling their thumbs waiting for the Foreign Office to bring in their victim . . .

It is all a sorry affair.

Chapman’s HOMER

One could be forgiven for concluding that Chapman would have had an impossible task in making sense of this mélange of assertions. It was perhaps ingenuous of him to refer to the ‘known facts’ of the case without having to define what he thought they were. I could suggest, on the other hand, that, while the preceding analysis might be nugatory for assessing the decisions that the playwright made, it does offer some other advantages. The above accounts must overall be of great value for anyone trying to establish exactly what did happen in those few weeks in May 1951 – if only because the obvious contradictions have to be inspected and resolved. It is true that, before the end of the century, some fresh perspectives from overseas commentators (such as Newton in the USA, and Modin and Mitrokhin in the USSR) did enter the arena to add new dimensions to the story, and offered further ‘facts’ to be checked. There was, however, not much new independent analysis during the next decade or so. The authorized history of MI5 then followed, but it was particularly feeble (as I shall explain next month). Its appearance as the implied ‘last word’ may however have discouraged any new analysis for a while. It was not until the National Archives, during the 2010s decade, threw up a variety of information on Philby, Burgess and Maclean, as well as the very revealing Personal Files on the Reeses, that inquisitive biographers tried to pick up the challenge.

It seems to me that Chapman, perhaps overwhelmed by the conflicting stories published, stuck with his attachment to Rees’s memoir, believing in the authority of such artifacts, but enhanced it to try to take advantage of the very topical information about Blunt’s unmasking, and his subsequent ‘confession’. If Chapman had constrained himself in this area, he might have avoided much unnecessary complexity, but he latched on to the fact that Blunt had played a role in arranging the escape, and then amplified it to a degree that presented him with some plot challenges. His decision created several fresh clashes with the chronology and geography of the events as described by various of the other chroniclers.

In my opinion, Blunt, for reasons of temperament, ability, and circumstances, could not have been a decisive leader of the project. Yet Chapman presents him as essentially bossing Vasily (Modin), issuing the orders, and instructing what the NKVD/MGB should do. (In that way, he endorses Burgess’s’ view of things in defiance of what Petrov reported.) Blunt would have struggled to acquire travel tickets and visas for the itinerary across Europe without drawing undue attention to himself. Moreover, if he seriously believed that he could send Burgess over for part of the way, and then have him return home, with Maclean reputedly having ‘given him the slip’, Blunt seriously underestimated the problems that Burgess, under surveillance himself, would have encountered with the authorities, having accompanied the known suspect in such an underhand manner, and abetted his escape.

Moreover, Chapman then had to deal with the vital and central episode in his story, Blunt’s searching for and incinerating incriminating papers that he found in Burgess’s flat. Recall – in Chapman’s scenario, that took place on the morning of May 26, the Saturday, because Burgess was able to get a breakfast message to Blunt that vaguely hinted at the danger represented by the contents of Burgess’s flat. The impression is that Burgess was somehow suddenly alerted to the fact that he had to accompany Maclean all the way to Moscow. First, Chapman had to create a McGuffin – the ‘What’s Become of Waring’ letter, which Burgess had written on Reform Club notepaper, but had placed with a postal collector in the countryside early on the Friday evening. (The ‘What’s Become of Waring’ idea is taken from Rees’s memoir, where he retrospectively reflects on Burgess’s character, but Chapman’s deployment of it is simply a highly imaginative addition to the screenplay.) Burgess may not have wanted to face his lover with the news by speaking to him on the telephone, but why did he not mail the letter from his Club, which action would probably have guaranteed the chance of delivery the next morning? And would Blunt interpret the message accurately?

And what had prompted Burgess’s sudden decision? Chapman does refer to the late decision to interrogate Maclean, and he shares the misapprehension that he was going to be hauled in on Monday 28. On the other hand, he never indicates that Burgess learned of that resolution. One clue that Chapman does offer, however, is an extended view of a very pensive, even, distraught, Burgess, immediately after Blunt has divulged the secrets of the plan to him, as if he then realized the enormity of what was about to happen, and resolved to defect as well. But why did he not discuss that outcome, and its implications, with Blunt, or take the time to clear out his flat at leisure? In addition, Burgess is shown to be in a very jaunty mood as he drives down to Tatsfield, which would be surprising given that he has probably seen his intimate friend Blunt for the last time, that there is a possibility that Blunt will not be able to clean up his possessions in time before MI5 gets there, and that he is facing a probably bleak residence in Moscow that he had not even imagined a few days before. (Rees wrote how much Burgess loved life in England.) It is psychologically very unconvincing.

The spotlight turns on Burgess’s relationship with Rees. Blunt is shown to inform Guy Liddell, gratuitously, that Rees has just gone down to Sonning, in a brief scene that is clearly dated as May 16, since Liddell’s desk calendar boldly informs us of the timing. (It serves as an intro to the next scene, in Sonning.) Yet that is a sharp departure from what happened in One of Us, where the stage directions state that the visit occurred on May 6. (This is itself a clumsy variation from Rees’s memoir, where he states that Guy arrived on Monday, May 8. We know that Burgess arrived in Southampton on May 7.) It might have seemed to Chapman that it would be dramatically more sensible for Burgess to contact Rees, in order to ensure that he would stay silent, when the plot had been hatched, and thus a mid-May visit would make sense. Yet in the stage version, Burgess tells Rees that Maclean is already in danger, and that Blunt is organizing a plot for his exfiltration. That would have been the day after Burgess disembarked at Southampton, when he did not yet know where Maclean lived, even. The description of the advanced state of the project is simply absurd.

And why would Burgess, who has reputedly not seen Rees for some time, want to inform him about the plot? Would it not have been better for him and Blunt to ignore Rees, carry out the procedure for exfiltrating Maclean (no matter to what extent Burgess was to accompany him), and leave Rees in the dark, so that he would not make any impetuous approach to MI5? Stirring up a hornet’s nest with Goronwy – as well as Margie, who had witnessed the ‘ratting’ episode at the Gargoyle Club the previous November – would appear to introduce some unnecessary risk to the equation. Why was the extraction of the promise from Rees not to divulge anything considered so important, especially when it was bound to cause tension between husband and wife? Moreover, Chapman inserted one or two provocative incidents in the story: he has Burgess noting early on that Rees will be away at All Souls on May 24, and the exchange between Margie and Goronwy indicates that she had had no luck in getting through on the telephone to Rees while he was in Oxford – not how her husband described it in his memoir.

The problem is that the account in A Chapter of Accidents is utterly unbelievable, as Burgess would not set up the self-invitation from the USA, and then rush to Sonning, simply to discuss his imminent expulsion from the Foreign Office and his probable job with The Daily Telegraph. Yet Chapman’s interpretation (which is not supported by anything Rees wrote) is likewise ridiculous, in that Burgess would not be describing the planned exfiltration of Maclean just after he had disembarked, when he had not even talked to Maclean. There must be another agenda behind the visit (which is hinted at by Chapman and other authors), one to which I shall have to return soon.

Lastly, The Fourth Man makes several glaring errors. It refers to the Soviet organization as the KGB, but the KGB was not created until 1954, after Stalin’s death. (This error appears in many of the books described above, as a kind of shorthand for the various guises the Soviet Security Service took on since the days of the Cheka.) Rees and Burgess discuss Maclean’s fate in terms of a probable death sentence hanging over him, as if that intensified his despair, but that punishment, as part of the Treachery Act, applied only to treasonable activities carried out to help a country with which Great Britain was at war. Chapman presents Bernard Miller, Burgess’s supposed ‘pick-up’ from the Queen Mary, as being in bed with him in mid-May. But Miller was not homosexual, he disembarked from the Queen Mary in Cherbourg, and he did not arrive in London until May 23. Chapman indicates that the shortlist for HOMER was reduced to Maclean as late as May 16, when it had happened over two weeks before. When Blunt incinerates Burges’s possessions, the last item visible is Guy Burgess’s Communist Party card for 1951. He may have been a member of the Party in the early 1930s, but he was certainly not so in 1951.

Other touches are simply clumsy. Just before his assignation with Modin in adjacent stalls in the Gentlemen’s Public Lavatory, Blunt, in prim office garb, with rolled-up umbrella, checks his watch before marching to the rendezvous, where a policeman is present. It is absolutely incongruous and absurd. In another scene, Burgess and Maclean, supposed to be under surveillance, crowd into a public telephone-box in broad daylight to await a call from Blunt. That is similarly ridiculous.

Conclusions

Did The Fourth Man succeed as an artistic venture with political overtones? As a reliable record of what events led to the escape of Burgess and Maclean, it is feeble and misleading, but one could not expect any viewer to know enough about the evidence behind the action to be able to challenge the apparent facts. Even today, because of the successful job that intelligence officers and civil servants such as George Carey-Foster, Patrick Reilly, Roger Makins, and Dick White executed in planting false trails, the mendacious memoir of Rees, the prevarications of Melinda Maclean, the unreliable testimony from Jackie Hewit, the boastfulness of Yuri Modin, etc. etc., even the ‘experts’, such as Nigel West, have a difficult time tracing an accurate and convincing sequence of events for those heady days in May 1951.