For casual browsers, here is the short version of the book review, in the form of a clerihew:

Margaret Thatcher

Vigorously hounded ‘Spycatcher’.

For Wright’s attorney the clincher

Was her indulgence to Pincher.

For those of you who are fully paid-up subscribers to coldspur, and want to read the full version, start here:

Contents:

Introduction

Parallel Narratives

The MI5 Report

Jonathan Aitken

The Plot

The ‘Spycatcher’ Trial

The Epilogue

Miscellaneous

Conclusions

Appendices 1-9

**********************************************************************

Introduction

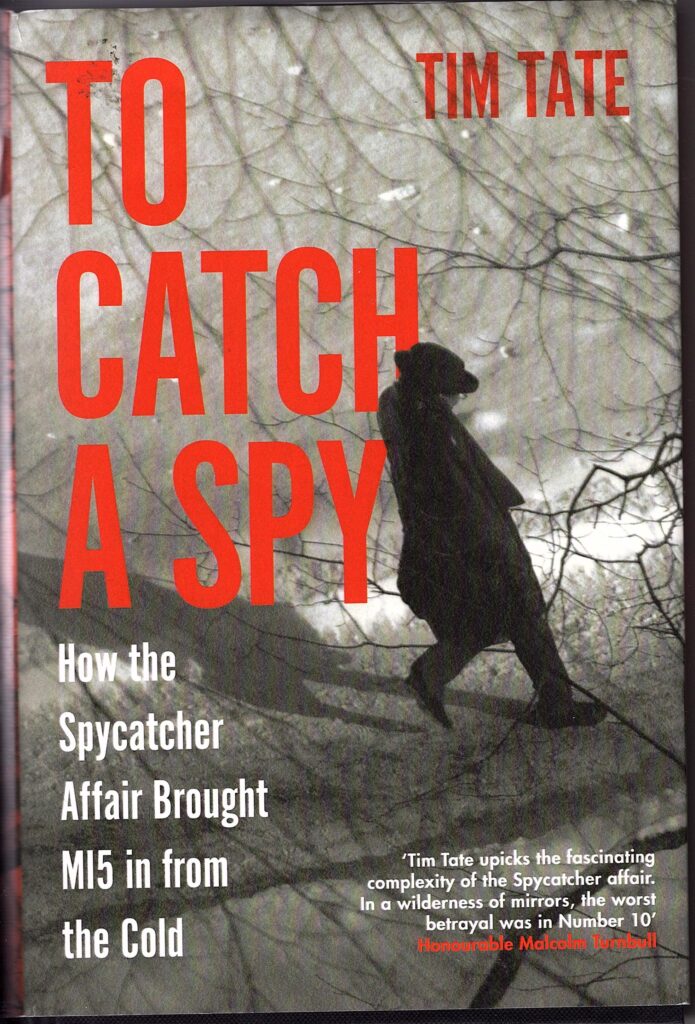

Someone (I do not recall who or where) recently pointed out that the one thing that Peter Wright, the author of Spycatcher, failed to do was to catch any spies. It seems that Tim Tate did not get the email, since he has titled his new book on the ‘Spycatcher’ affair To Catch A Spy. Since Wright was keen to boast that he was ‘the only senior officer in MI5 to have spent twenty years in counter-espionage’, either he was not a very capable sleuth, or else his energies were for some reason thwarted. It is the latter tale that Wright vigorously promoted, and it is the story that Tate has chosen to endorse. As an account of the catalogue of woe that Margaret Thatcher and her administration brought down on itself in trying to suppress Wright’s memoir, To Catch A Spy is, for the most part, excellent: on the other hand, as an investigation into the realities of Wright’s claims that MI5, and the UK government in general, were riddled with Soviet spies, it does not grab the nettle, makes some spectacularly wrong assertions, and is disappointingly bland and incurious. It fails to unravel the complexities of the establishment plots to control the narrative, and is far too accepting of what Wright and his accomplices claimed about the extent of Soviet penetration.

I approach volumes on intelligence like this one with three primary questions: What is the track-record of the author, and what credentials does he [or she] have? What fresh sources does he bring to the table that may cause a revised history of the events to be justified? What methodology does he apply in sifting the evidence, and dealing with the multiple obfuscations and dissimulations that inevitably bedevil the records and testimonies?

I had encountered Tate in two previous books: Hitler’s Secret Army, and Agent SNIPER (published in Britain as The Spy Left Out in the Cold), his biography of the Polish defector Michal Goleniewski. He describes himself as a documentary film-maker and investigative journalist. I gained much from both books, although I believe Tate exaggerated the Nazi threat in the first book, and Goleniewski, who rapidly entered the predictable world of fantasy when his intelligence ran out, hardly had enough substance to warrant a full book about him. Rating: B.

On sources, Tate has performed a phenomenal job in rooting out arcane material – especially in British Government archives, where critical information was released to select historians, but weeded from the files before they were released to the public – with many still withheld. He has also scoured the records of the ‘Spycatcher’ trial in New South Wales to deliver valuable new material from the transcripts and affidavits. He has secured several personal communications with prominent members of the controversy, from Nigel West through Jonathan Aitken and others, to Peter Wright’s offspring (although such confidences should not be automatically trusted). Rating: A-.

Sadly, Tate has not applied the methodology of a professional historian to his material. (The qualifications for adoption as a Fellow of the Historical Society must be low.) He is far too trusting of what Wright said in his book, and in his affidavits, when careful checks and third-party testimony lead one quickly to the conclusion that he was a consummate liar. His exaggerated respect for Wright is shown by the fact that a majority of the chapters in his book are introduced with a statement from him. All too often I looked up a reference in Tate’s Endnotes to find it simply cited a page from Spycatcher, and Tate shows no discrimination in deciding when Wright should be believed, and when he should not. That weakness extends to his coverage of other witnesses. Tate also quotes, far too often, Christopher Andrew and his unverifiable references to ‘Security Service Archives’ in Defending the Realm, and he never attempts to engage the authorized ‘historian’. He accepts all such information as gospel – except when it tends to contradict his main thesis. The unwillingness to challenge Wright’s lies is in contrast to his justified contempt for the prevarications and perjury of Sir Robert Armstrong. This failing undermines a dominant theme in his book – that dozens of Soviet spies remained unchallenged and unprosecuted in Britain’s offices of state. I was tempted to redeem Tate’s grade slightly in recognition of the industrious work he has performed in comparing declassified files with published texts, but found the process of unravelling his cross-references so laborious that I stayed with my more negative appraisal. Rating: C+.

To illustrate some of my points, I present some extracts from Tate’s Introduction, with commentary. It is not a good beginning.

P 1 “Peter Wright, a senior Security Service officer for more than twenty years, had been at the centre of many of the most damaging intelligence scandals of the 1950s and 1960s. He had been MI5’s chief counter-espionage officer, leading its efforts to catch Kim Philby, to uncover Soviet penetration of Britain’s twin intelligence agencies, MI5 and MI6, and to root out the long tentacles of Moscow’s infamous ‘Ring of Five’ spies, embedded in the heart of the British Establishment.”

Wright had not been a senior MI5 officer for twenty years. He had been recruited in 1955 as a scientific officer, and had been appointed head of research in D Branch in January 1964. By then, Guy Burgess was dead, Donald Maclean had been in Moscow for thirteen years, John Cairncross had been encouraged to resign in 1951 after owning up to espionage and had formally confessed in December 1963 after being named by Anthony Blunt, Kim Philby had absconded from Beirut in 1963, and Blunt had confessed to being a Soviet agent not in April 1964 but in late 1963 (as my original articles strongly hypothesized, at https://coldspur.com/the-hoax-of-the-blunt-confession-part-1/ and https://coldspur.com/the-hoax-of-the-blunt-confession-part-2/ , and which I reinforced last month, at https://coldspur.com/an-anxious-summer-for-rees-blunt/ ). Wright was never head of counter-espionage, although he did chair the combined MI5-MI6 FLUENCY Committee to investigate Soviet penetration, and before his retirement he was a special adviser to Michael Hanley, the Director General from 1972 to 1978. That the ‘Ring of Five’ had tentacles, and that the level of commitment to the Soviet cause dedicated by the persons supposedly representing them was high, is not questioned by Tate. He is intuitively sceptical of anything MI5 directors-general say, and (for instance) criticizes Antony Duff for carrying out a stringent internal inquiry in 1987 without reaching out to contact Wright himself!

P 2 “It [the government] had also allowed retired Director General Sir Percy Sillitoe and its in-house traitor Anthony Blunt to write their own memoirs . . . .”

Unlike Sillitoe’s book (which boasted a foreword by Clement Attlee), Blunt’s memoir was never published. In light of other indiscreet revelations provided by unnamed MI5 officers, coupling Sillitoe and Blunt is a bizarre choice. In PREM 19/1952, John Masterman’s The Double Cross System in the War of 1939-45 is listed alongside Sillitoe’s memoir as the only other book by an ex-MI5 officer that received authorization by the government – although that statement misrepresents what was in fact a very awkward process.

P 2 “Wright’s allegations of Soviet penetration of MI5, and of MI5’s habitual law-breaking, were simultaneously admitted as true for the purposes of the Australian trial but pronounced false in the House of Commons.”

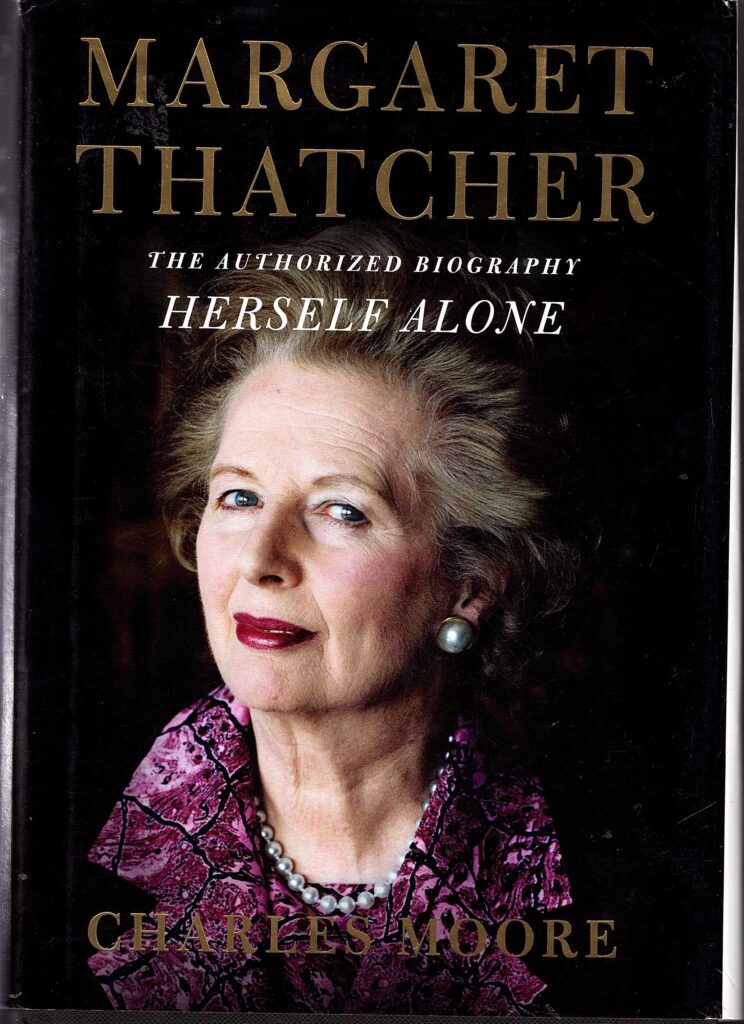

That statement constitutes a dubious representation of the truth. Tate echoes it on page 245, where he writes of the government’s ‘admission that – for the purposes of the trial – every word in Spycatcher was true’, and again on page 290, where he claims that Thatcher’s denials to the House of Commons about the Wilson plot were contradicted by the fact that the government had accepted during the Spycatcher trial that ‘all Wright’s allegations were true’. I cannot locate any passage in Tate’s book that supports this thesis: the whole point of the Government’s defence was that Wright’s claims could not be dissected at all because they were all confidential. I believe that these assertions may be a lazy paraphrasing of what Charles Moore wrote in Volume 3 of his biography of Margaret Thatcher, on page 239. The relevant text runs as follows: “It [the British government] agreed, for the purposes of the court case alone, to admit the truth of Wright’s allegations and information, disputing only the author’s right to publish them. This was a legal technicality, but of course it was not understood as such.”

This is an uncharacteristically sloppy passage by Moore, and his heavily annotated book provides no sources for these claims. With whom did the government ‘agree’? What was the implication of ‘for purposes of the court case alone’? How public was that statement? What are the implications of the words ‘legal technicality’? Who were the agents and figures who did not ‘understand it as such’? Moore predictably did not start to answer such questions, but, in my opinion, Tate should have taken it upon himself to analyze them further before promoting the underlying assertion as gospel.

P 4 “The Security Service was determined to cover up the truth about Soviet moles in its ranks, to conceal its habitual domestic law breaking and to prevent any democratic supervision of its actions. . . . . . At its behest, the Prime Minister and the Cabinet Secretary conspired to defuse the ticking time bomb of the investigation into Sir Roger Hollis by leaking top-secret information.”

While Tate appears, rather alarmingly, to have pre-judged that the existence of moles within MI5 was an inarguable fact, he provides no evidence of MI5’s determination to cover up such a ‘truth’ in the critical period under review. As he records, when Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister in 1979, the Security Service presented to her a detailed report that outlined the investigations into possible ‘moles’ in the service, and particularly that into Roger Hollis. Yet the Director General of MI5 at the time (1978-1981), Sir Howard Smith, does not even appear in the Index of To Catch A Spy, and it is moreover unlikely that Armstrong and Thatcher would have been persuaded to engage in such conspiracies by the arguments of such a weak character. The claim that it was MI5’s ‘behest’ that convinced Thatcher and Sir Robert Armstrong to initiate the leakage operation thus lacks any supportive evidence, and runs counter to the narrative as presented in Tate’s text. [In Volume 3 of his biography of Thatcher, Charles Moore attributes Smith’s supportive role in responding to Pincher to a conversation he had with Lord Armstrong, as he became, and the claim is thus not seriously verifiable. Moreover, in Volume 1, Moore had reported that the Director General had advised Thatcher not to make any announcement when the Blunt rumour first surfaced in ‘late’ 1979. Since Moore recorded the D-G as being Michael Hanley, who had retired the previous year, this unsourced item must therefore be treated as another vague observation. The whole section covering the Blunt revelation is very loose.] After Their Trade is Treachery began serialization in the Daily Mail, the newspaper reported that Thatcher had ordered Smith to provide an explanation, but that may have been a supposition inserted by Pincher.

P 4 “He, with official approval and the backing of Lord Victor Rothschild, himself a former spy, used this material to publish a book about the case in 1981. And Pincher’s secret co-author – as the British government knew – was Peter Wright.”

Lord Rothschild – who strongly protested when his name appeared in the form given by Tate, by the way – was never a ‘spy’ for British intelligence (though he had been an ‘agent of influence’ for the Soviets). [Tate, mimicking the unfortunate example of Tom Bower, who titled his biography of Dick White The Perfect English Spy, regularly classifies counter-espionage officers as ‘spies’, a practice that may have started with Isaiah Berlin’s career advice to Philip de Mowbray.] Tate also fails to draw clear lines in the conspiracies to exploit Wright’s findings via the media of Chapman Pincher. In his main text, he judges it a ‘coincidence’ that Armstrong and Thatcher were plotting to use Pincher at the same time that Rothschild and Wright were doing exactly the same thing. He fails to explain why the backing of Rothschild was significant if ‘official approval’ had already been registered.

As a parenthesis, I point out that I have added several Appendices to this report, the first and second consisting of a comprehensive guide to the National Archives files used by Tate – which would have been a useful component of his supportive material – and a summary of the information exceptionally provided to Charles Moore. The others constitute a record of the incumbents in critical positions during the period of these events (broadly 1945-1990). I compiled these partly for my own edification, as it is useful to be able to verify personalities when a record refers simply to the ‘Prime Minister’ or the ‘Director General’ of the time, but also to show the general lack of continuity among most political appointees or electees. MI5 and MI6 reported to the Home Office and the Foreign Office, respectively, so I include the Ministers responsible, many of whom must have been overwhelmed by the intelligence shenanigans they encountered, but did not remain long enough in office to have any influence. Amid all this was the relative permanence of the Cabinet Secretaries, solidly ensconced in the engine-room of the ship of state, with only four such civil servants holding the office between 1947 and 1987, thus confirming the importance of their interest and actions as the investigations into Soviet infiltration evolved. Robert Armstrong uniquely served only one Prime Minister – Margaret Thatcher.

Parallel Narratives

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Tate’s story is the manner in which his narrative and that of Christopher Andrew run on parallel but contradictory lines. Tate shows much ingenuity in expanding on Pincher’s account, explaining how in early 1980 the MP Jonathan Aitken approached Thatcher and Armstrong to warn them about the level of Soviet penetration in the intelligence services, augmenting what a report given by MI5 to Thatcher soon after her assuming office in May 1979 had declared about the FLUENCY investigation. That initiative led to a plot by Thatcher and her Cabinet Secretary to try to deliver the unsavoury news about Hollis through a supposedly friendly journalist, Chapman Pincher. As I pointed out above, Tate never mentions the current MI5 Director General, Howard Smith. Andrew, on the other hand, says nothing about Their Trade is Treachery until describing the occasion on which Thatcher was forced to make her statement in the House of Commons. He writes nothing about the MI5 report that educated her to the threats back in 1979. According to him, the ruse to employ Pincher was cooked up solely by Rothschild and Wright (although Andrew does confirm that Wright had been leaking information to Pincher for some years). On the other hand, Andrew has several things to say about the ineffectual Howard Smith, who had been brought by James Callaghan from the Embassy in Moscow to lead MI5 in 1978, but thereafter stayed in the background, was a weak leader, and did not concern himself with operational affairs.

It is perennially difficult to assess how reliable Andrew’s judgments are. We do not know (for instance) the extent of his access to MI5’s files. (He describes it as ‘virtually unrestricted’, but how does he know?) We do not know how many he himself inspected, or whether those cited were perhaps summarized or sanitized by his research team of ex-MI5 officers. We do not know whether relevant files from other government departments were placed before him: certainly he cites resources such as the FCO and the PREM categories, but his narrative would suggest that some vital files escaped his notice. The status of the files his team did inspect – whether still unclassified, or since released – is unknowable. It is a very sorry state of affairs that I – and other historians – have lamented.

Andrew’s oversight in this particular domain is all the more remarkable since Pincher first referred to Aitken’s letter to Thatcher, dated January 31, 1980, in Their Trade Is Treachery (hereafter referred to as TTIT; 1981) and published its full text as an Appendix in his 1988 book A Web of Deception. Pincher, rather disingenuously, claimed that he had gained most of his material for TTIT from Aitken, who had, in turn, been indoctrinated by James Angleton of the CIA, and then further educated by Arthur Martin (at that time retired from the intelligence scene). Pincher then claimed that Thatcher and Armstrong had brushed off Aitken’s warning, assuredly after receiving guidance from MI5 to ignore it (though Pincher provided no evidence of such), and that Armstrong did not become alive to the imminent revelations about Hollis until he received an early copy of TTIT in January 1981. His thesis (as I explained in coldspur two months ago, at https://coldspur.com/the-still-elusive-victor-rothschild/ ) was to judge that the government had stumbled into allowing TTIT to be published out of a misguided concern for secrecy rather than from any devious plotting.

Tate’s coup has been to exploit archival material declassified in 2023 to blow a hole in both these stories, thus resolving the conflicts that puzzled me last month – why Thatcher and Armstrong would behave so passively over Pincher’s subversive book, and why Rothschild would risk so much in dealing with, and encouraging, Wright. Reproducing information from PREM 15/591, Tate shows that Thatcher and Armstrong considered, in June 1980, that allowing the leaked story to be communicated by a ‘sympathetic’ journalist, namely Pincher, would defuse the volatile Hollis situation and allow them to control the risks embodied by Wright. These revelations hold enormous significance for the encounters between Rothschild and Wright, and the ‘introduction’ of Pincher, in late summer 1980. But first, I want to step back and consider the implications of the 1979 MI5 report, and the incongruous entry of that popinjay and perjurer* Jonathan Aitken into the narrative.

[* Aitken was convicted of perjury in 1999, and served prison time for it.]

The MI5 Report

The May 1979 report, which consists of eight pages, in PREM 19/120, offers a broad summary of the (unidentified) FLUENCY Committee investigations. It is anonymous, but was probably compiled by the Deputy Director General, John Jones, who had been working for MI5 since 1955. It explains the disclosures by one defector (Gouzenko) and one would-be defector (Volkov) that had encouraged the inquisition, and Tate’s text briefly outlines the trail that led to Roger Hollis’s being considered the prime suspect. Yet it also provided an important qualification: “No information was discovered to confirm the supposition of espionage . . .”, which suggested that all the claims of ‘failures’ of counter-Soviet operations rested on shaky ground. My contention has always been that the first responsibility of MI5 and MI6 should have been to try to determine why such projects had misfired, and whether such failures could reasonably be attributed to leakage, rather than blundering around looking for scapegoats. For instance, in ‘Peter Wright’s Agents and Double-Agents’ (see https://coldspur.com/peter-wrights-agents-double-agents/ of May 2022), I debunked the notion of MI5’s having a hope of running ‘double-agents’ against the Soviets in London, and I expanded on this theme earlier this year in ‘Some Problems with Westy’ (see https://coldspur.com/some-problems-with-westy/ ).

Yet Tate disposes of this report in a very perfunctory manner. First of all, his introduction is inaccurate. On page 115, he states that Thatcher would not have been able to rely on Sir John Hunt for guidance, since she had replaced him with Sir Robert Armstrong in October. Hunt, however, had been supplying the Prime Minister with analysis, draft written responses should the crisis erupt, and supplementaries to possible parliamentary questions, from her accession on May 4 right up until October 10, five days before Armstrong officially took over. (Tate lists only Volume 3 of Moore’s biography of Margaret Thatcher in his ‘Selected Bibliography’.) In this communication, he showed how alive he was to the situation by pointing out that Blunt might a) initiate libel proceedings, b) make a public confession, or c) commit suicide. Armstrong’s first recorded memorandum is dated November 8th, after Climate of Treason had been published.

Furthermore, Tate misrepresents the essence of the MI5 report. He dedicates only a single paragraph to it, and summarizes it as referring to ‘the facts which had pointed at Hollis as the most likely traitor in its ranks’. Yet the report expressed no such opinion. It stated that there had been no evidence of penetration for twenty years. Over a hundred leads had been investigated (presumably including those that Wright identified), but they had been cut down to only five by 1973, and to a single case in 1976 – which was still being looked into. Tate’s immediate judgment is that MI5 ‘was determined to keep its political masters in the dark about the extent of the problem’ (p 110), but he offers no evidence for that conclusion, and appears not to consider that, since MI5 had opened up the project, the Security Service might have expected to receive further questions from their bosses about the process and the eliminations. Yet that apparently did not happen. Simply because MI5 was evasive and dilatory concerning the activities of some spies, it did not automatically mean that it was concealing information about a clutch of others.

In addition, nothing incriminating had been found against Graham Mitchell or Roger Hollis, and the judgment was that Volkov’s identification was much more likely to have been Philby rather than Hollis (even though the report characteristically misrepresented Hollis’s role during World War II). One of the most ridiculous suggestions is that, when Blunt resigned from MI5 in 1945, Moscow might have wanted a spy within the service to carry on the work, and thus they ‘activated’ either Mitchell or Hollis, or both – as if they had been waiting quietly in the wings for that day. Meanwhile, as Blunt admitted, he carried on supplying information to the Russians through the 1951 events (exploiting his excellent relationship with Liddell and White), and beyond – and was probably involved in the tip-off to Philby in 1963.

What is more astonishing is that in MI5’s report the original trigger for the investigation into possible infiltration was ascribed to an interview by MI5 of Philby’s wife Eleanor after the defection. She stated that her husband had become very nervous, and started drinking heavily (again) in 1962, and the Security Service assumed that one of the only five senior officers who knew about the renewal of the investigation into Philby must have leaked that information to him. That led to Mitchell and Hollis, but, later in the report, the author pointed out that Philby might well have become very anxious because of the news that the defector Golitsyn was starting to talk, and might be able to finger him – which indeed was the case. If Eleanor Philby’s claim truly was the prima facie cause for the whole inquiry, it rested on very shaky ground. Tate ignores that observation, preferring to trust the version that Wright offered.

Tate largely ignores the tenor and details of the MI5 report. I hoped, nevertheless, that he would apply some rigorous analyses of the failures claimed by Wright. Yet, in his critical Chapter 7, title ‘DRAT’ (the code-name for the investigation into Hollis), where he covers the allegations, he first refers to the August 1975 report submitted by Sir John Hunt, the Cabinet Secretary, to Prime Minister Harold Wilson, which mentioned in vague terms the possibility of espionage leads beyond proven spies, but then for his next seven sources relies almost exclusively on Wright’s testimony, from the Granada television program, from Spycatcher, and from his affidavit in Sydney. These are notoriously unreliable, as several commentators have pointed out. Tate later admits that Wright was accused by other MI5 officers of inventing evidence where none existed, but he largely ignores the consequences of such claims.

There have never been any documents released from the FLUENCY Committee, or the DRAT investigation, so Tate cites Christopher Andrew for two important anecdotes. In Defending the Realm, on page 511, Andrew wrote that Hollis and White, the respective chiefs of MI5 in 1965, had accepted the conclusions of the FLUENCY Committee that Soviet penetration of both services had endured, and that they authorized further investigations. The circumstances of these judgments are maddeningly elusive, as, again, Andrew is exploiting an unverifiable source. White’s reasoning, and the possibility that his protégé was influenced by him, must be one of the most important aspects of the whole case. And on page 517, Andrew describes a June 1970 report written by John Day titled ‘The Case Against DRAT’. (By then, both Hollis and White had retired, although White was active as Intelligence Co-ordinator for the Cabinet office until 1972.) Andrew was probably the only outsider who had read the report. In his Endnote, however, Tate writes: “The only account of its contents . . . . unsurprisingly denounces it as ‘threadbare’ and ‘shocking’.” Why would Tate characterize Andrew’s analysis in such a deprecatory manner? Does he think that Andrew was prejudiced? Why does he not trust Andrew’s assessment of the significance of its contents? Why did he not attempt to have a conversation with Andrew about it, as he did with other participants?

I should record that Andrew took a dim view of Wright and his fellow ‘conspiracy-theorists’. He wrote of Day’s paper: “It remains a shocking document – a classic example of a paper written to support a conclusion already arrived at which excludes important evidence to the contrary and turns on its head evidence which does not fit the preconceived conclusion”, and Andrew gives examples of Hollis’s positive track-record, and how misguided the characterization of Hollis’s roles was as presented in the report. Now, one could not expect Tate to argue on the merits of Day’s report, since he had not read it, but it seems to me utterly cavalier and irresponsible of him not to record Andrew’s judgment, and instead to imply that Andrew was party to a cover-up. I encourage readers to re-inspect these pages 517-521: Andrew also cites at length a 1988 report issued by K10R/1 that catalogues Wright’s dishonesty and fabrications, and points to the lack of intellectual rigour on the part of many of the investigators. Sadly, it is another of those anonymous items footnoted solely as ‘Security Service Archives’. Yet Tate should have at least recognized its existence.

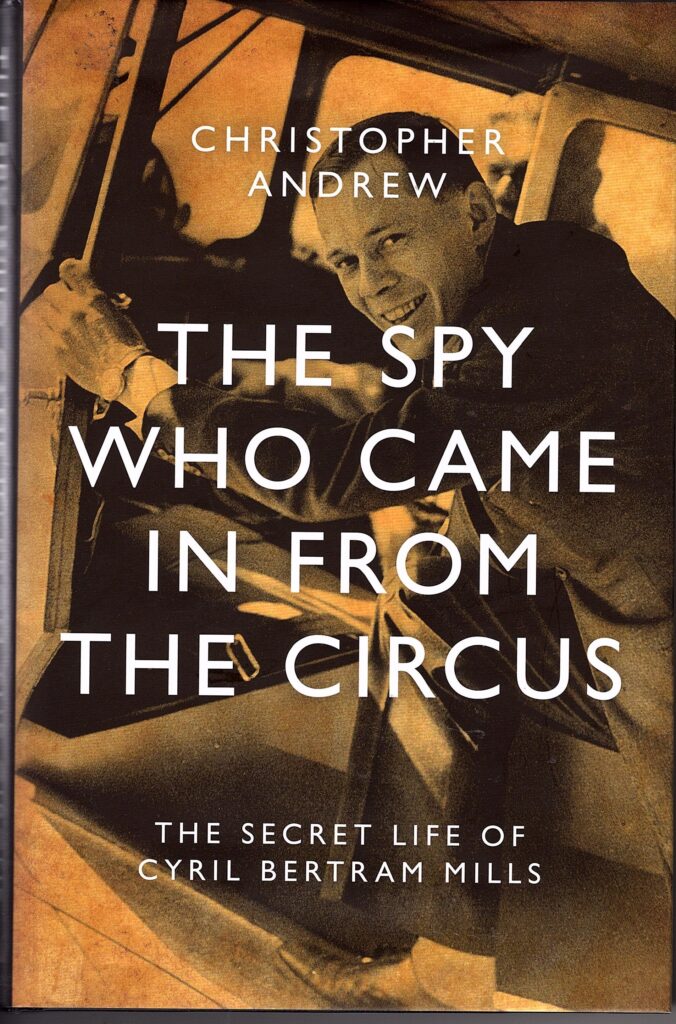

Andrew has recently added further testimony to support one of his claims – that Wright had created false evidence to incriminate Hollis. In his 2024 biography of the MI5 officer Cyril Mills, The Spy Who Came in from the Circus, he reinforces his argument by quoting Mills’s disparaging view of how Wright, in Spycatcher, completely misrepresented Mills’s contributions in surveilling the Soviet Embassy. When Wright’s book was published, Mills – who had up until then been a stickler about confidentiality, and honouring his commitments – told his family that the real traitor was not Hollis, but Wright himself. The distortions by Wright that Mills documented for his bosses were later confirmed through an internal MI5 inquiry.

Tate makes no mention of another distinguished critic of Peter Wright – Hugh Trevor-Roper. In a withering review of Spycatcher in the Spectator of October 10, 1987 (republished in The Secret World of 2014), Trevor Roper lambasted Wright’s ‘advocacy coloured by personal prejudice’, noted some further errors to those that had already been listed, and characterized his approach as ‘somewhat paranoid’. Trevor-Roper was also the first to refer to the complaints made by Cyril Mills, as echoed by Andrew. He vented at the hypocrisy displayed by Wright, who claimed that he was on his crusade for the public good when he had already admitted that MI5 was ‘mole-free’ by the time the book was published.

That intellectual flabbiness was evident at the top is, nevertheless, undeniable. Andrew cites another unverifiable archival item in which Furnival-Jones (the Director-General between 1965 and 1972), ‘despite his own scepticism about “The Case against DRAT”’, informed the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Home Office (Sir Philip Allen) and the Cabinet Secretary (Sir Burke Trend) of the investigation of Hollis, but for some reason failed to tell either the Home Secretary (Reginald Maudling) or the Prime Minister (Edward Heath), who had replaced Wilson after the June 1970 election. One might have expected a disciplined leader of MI5 to have carried out his own rigorous assaying of his subordinates’ extravagant claims before sharing with his political masters the facts of the internal divisions, but Tate characterizes Furnival-Jones as amiable and unenterprising.

Thus Tate allows Wright’s presentation of the ‘twenty-eight solid cases’ to hold sway. I shall not here analyze in depth such episodes, but merely record some of the obvious errors made in Wright’s presentation of the interrogation of Hollis in 1970, as recorded by Tate, since I have written about these beforehand. The first is Volkov’s claim about ‘the acting head of a section of the British counter-intelligence directorate’. Tate echoes the assertion that that must point to Hollis, the ‘acting head’ of F Branch during WWII. Yet B Branch was responsible for counter-intelligence; the mission of F Branch was controlling subversion, and Hollis was its permanent head after June 1941. Philby in MI6 was the obvious candidate. The second is a complete misrepresentation of Gouzenko, and the ‘ELLI’ accusations. The third is the outlandish suggestion that both Hollis and Mitchell owned the combination of length of service and access to information that would have allowed them to tip off Philby before his defection. To this, Tate notes without comment Wright’s claim that the evidence against Hollis was ‘far greater than any of the other people’. It is quite absurd. If Tate sincerely believed that the MI5 report was a stitch-up, and that Wright’s case was strong, he should at least have examined the evidence more carefully, and not have misrepresented the conclusions of the report.

Jonathan Aitken

Aitken’s insertion of himself into the controversy is quite extraordinary. Aitken had become a Conservative Member of Parliament in 1974. He was a colourful showman of solid ‘pedigree’, with a varied and stimulating background career. He had been introduced to James Angleton at the Army and Navy Club in December 1979, whereafter events took an alarming shape. Angleton expressed his suspicions about the security of Britain’s intelligence services, introduced him to Arthur Martin (now employed as a clerk in the House of Commons), and Aitken was excited enough about what he was told by Martin and his wife (who had been Guy Liddell’s secretary) to join the bandwagon.

On January 31, 1980, Aitken thus wrote a long letter to Margaret Thatcher, attempting to bypass normal Civil Service channels, outlining his concerns, and recommending action. (Tate refers to it as an exhibit of the Supreme Court of News South Wales: as I mentioned earlier, the full text appears as Appendix A in Pincher’s A Web of Deception, and it has recently been published in PREM 19/951.) It comprises an astonishingly arrogant set of largely unsubstantiated claims, laying out a supposed case against Hollis, and asserting that ‘Hollis and Mitchell between them recruited other unidentified Soviet Agents into the Security Service’, and that it followed from that the Security Services [sic] ‘may still be severely penetrated today’. In summary, he recommended a full independent inquiry, an interrogation of Mitchell (Hollis was dead), statements to be made to the House of Commons, and a reform of the Security Service with a view to amalgamating MI5 and MI6. He signed off by expressing his hope to the Iron Lady that his suggestions would be ‘helpful’.

An even more melodramatic dimension to this outburst is the background. When Aitken met Angleton, he was apparently on his honeymoon, having just wedded Lolicia Azucki. Yet he had for some time before been dating Thatcher’s daughter, Carol, and had jilted her just after the election in May 1979, an event that apparently provoked almost as much grief to the Prime Minister as it did to her daughter, and caused her to overlook him for a ministerial post. (As a woman of traditional customs, Mrs. Thatcher may well have wanted to ask Aitken if his intentions towards her daughter had been honourable. Charles Moore wrote that she ‘deliberately overlooked his talents’ after he dumped Carol.) Thus the bold approach could be interpreted in different ways: as a cold-blooded gesture to remind his boss of his independence and imaginative ways; as an innocent and sincere initiative, since he might have supposed that romance was inevitably a messy business, but outside the realm of politics; or as a means of trying to ingratiate himself with her by genuinely alerting her to a real and present exposure. In any event, one might have expected Thatcher to have responded to his unsolicited advice with disdain.

Indeed, some years later, when confronted by Aitken again on the need for parliamentary oversight of MI5, she replied (as Tate records, citing Aitken’s biography of Thatcher): “What rot! That would mean people like you poking their noses into security matters they know nothing about!” It is a shame that she did not respond that way back in February 1980, although, with her rather two-dimensional view of the world, she was as much a novice in the world of intelligence as Aitken himself was. Outwardly, that was what happened. The letter nevertheless found its way to Sir Robert Armstrong (as Tate reports), who advised her to ignore Aitken’s recommendations, and a few weeks later Aitken received a curt response, indicating that Thatcher knew about the allegations.

The Plot

Yet Martin continued to leak. Aitken later told Tate that he was not concerned about the Official Secrets Act. Jonathan Penrose and Chapman Pincher were reported to be working on new embarrassing stories. It was probably Pincher’s approach to the Attorney-General Sir Peter Rawlinson, indicating that he was writing a book about Hollis, and was looking for some government help, that provoked the fateful decision by Armstrong and Thatcher. On June 10, 1980, Armstrong wrote to Thatcher, suggesting that Pincher, as a friendly right-wing journalist, might be relied upon to defuse the coming Hollis scandal by declaring that he had been found innocent, by the original investigation as well as by Sir Burke Trend’s lengthy analysis. Thatcher soon agreed to the scheme, although the cut-out of the Attorney-General was used to provide deniability about an official government leak. As Tate writes, the move was not only probably illegal, but also naive. “Armstrong grossly underestimated Pincher’s willingness to cause mischief and his genuinely extensive contacts among the group of dissident molehunters who fervently believed in Hollis’s guilt.”

Thus the conspiracy to try to exploit Pincher as a way of muffling Martin – and Wright – has to be seen in a new light. Tate presents the parallel negotiations between Wright and Rothschild as completely unrelated to the Armstrong/Thatcher dealings with Pincher. “By a remarkable coincidence,” he writes, “Rothschild’s plan for publishing Peter Wright’s dossier involved the same intelligence muckraker.” Yet Rothschild had been in contact with Wright for some years, he had been keeping MI5 informed of Wright’s grievances and plans, he had been feeding Pincher with juicy tales from MI5 for some time, he had been in regular contact with Dick White on intelligence matters, he had his own ambitions for playing a dominant role in the Intelligence Services *, and he was on close terms with Armstrong. Furthermore, he had experienced that visit when in hospital (almost certainly by White: see https://coldspur.com/the-still-elusive-victor-rothschild/ ) where he had been encouraged in the plan to dismantle the Wright detonator by transferring the authorship elsewhere. He later requested cover when Wright planned to reveal his role at the trial, and warned Armstrong that he would disclose the names of other conspirators, prominently Maurice Oldfield #, if the Law continued to harass him. He was the ideal candidate to be the medium for the Armstrong-Thatcher plot.

[* Tate reports, using Moore’s biography of Thatcher, that Rothschild had in June 1979 recommended himself to the Prime Minister for the post of overseer of both Intelligence Agencies.

# Later in this report I debunk the notion that Oldfield would have been involved.]

Dick White is noticeably absent from Tate’s account of this period. Indeed, he has fewer entries in Tate’s Index than does Nigel West. Yet it is difficult not to see him as the ghost in the machine. As I wrote in my August posting, a few years later White told his biographer that he had warned Rothschild not to get involved too deeply with Wright. But Rothschild was dead then, and it was a typical example of self-serving mendaciousness from the man who for decades had been pulling the strings behind the scenes to protect his own reputation. I am confident that White and Rothschild were as involved with the plot as deeply as were Armstrong and Thatcher.

Before long, however, things began to turn sour. Pincher turned out not to be the compliant and sympathetic supporter Armstrong had judged him to be. For some reason, Rothschild was sluggish with his payments to Wright, who became impatient. When the first reactions to TTIT were somewhat quashed by Thatcher’s denials, Pincher wrote to Wright requesting new stories. Wright believed that he should be receiving royalties from the serialization of TTIT in the Daily Mail. Wright was angered by the way that Thatcher had evaded the challenges in her public statement, and wanted to renew the battle. He started to seek new outlets and fresh collaborators. Meanwhile, Armstrong and Thatcher had constructed a huge future hole for themselves by not taking any action to censor TTIT. The file PREM 15/591 shows the level of confusion reached, as memoranda are exchanged offering reminders that they were not officially supposed to have seen TTIT yet, and disingenuous questions being lobbed around as to who Pincher’s informant could possibly have been. And that error would turn out to be the vital factor that made the ‘Spycatcher’ trial such a disaster for Her Majesty’s Government.

One of the triggers that prompted Wright’s ire was the statement that Thatcher made to the House of Commons on March 26, 1981. Tate categorizes all three of her major points as ‘substantially false’, but I think he is being a bit shallow. Thatcher was careful to state that the leads gained by MI5 suggested that there ‘had been a Russian intelligence agent at a relatively senior level in British counter-intelligence in the last years of the war’, and she reduced the pressure on Hollis by stating that the leads could have pointed to Philby or Blunt. Wright, on the other hand, recalling the conclusions of the Fluency Committee, in his later affidavit asserted that the evidence of penetration had occurred ‘throughout the fifties and early sixties’, which would probably exclude Blunt *, and, since the betrayed operations were carried out by MI5, would presumably take a by now much less influential Philby out of the picture. His point on timing was no doubt correct, but no one who was hearing these statements for the first time knew exactly what Fluency had reported. On the other hand, Thatcher was essentially correct in the way she described how Burke Trend had examined the evidence in the files, and how he had offered a corrective to the shaky accusations made by Wright and his team. When Tate writes: “Her account of Trend’s verdict was the clearest evidence of her willingness to lie to parliament”, I believe he picks the wrong target.

[* I should point out that, in PREM 16/2230, John Hunt reports that Blunt had admitted providing information to the Soviets up until 1956. Of course, Blunt may have been lying, and he was probably involved with Philby’s escape in 1963.]

The ‘Spycatcher’ Trial

The account of the trial is where Tate really gets into his stride. Readers may be familiar with the broad outlines from Andrew’s history, from Malcolm Turnbull’s The Spycatcher Trial, and Richard Hall’s A Spy’s Revenge. They can cheerfully skip Chapman Pincher’s mendacious account in The Spycatcher Affair: A Web of Deception (although Tate lists it in his ‘Selected Bibliography’.) The trial in which Thatcher sent out Armstrong on a fool’s errand is the prime focus of Tate’s attention, and drives his story of how MI5 was placed into a proper statutory position (’Brought in from the Cold’) after the experience. The vital – and winning – point in the argument of the defence was that the government had taken no suppressive action in the cases of TTIT and Nigel West’s MI5: A Matter of Trust, even though both works had shown clear evidence of the leaking of secrets by intelligence insiders. What makes Tate’s narrative outstanding is the fact that he has carefully exploited files that have been declassified in the last few years, and, what is more, has identified several critical passages derived from secret archival material that was made available to Charles Moore, the authorized biographer of Thatcher (in particular Volume 3, 2019), and to Ian Beesley, who wrote a monumental Official History of the Cabinet Secretaries (2017), but which were removed from the files before they were released for public inspection (if the relevant file has not been permanently ‘closed’).

The government was in a bind in trying to ban the publication of Wright’s book. It had not seen the full text, of course, but it had to claim that the complete story was too confidential to be dissected and discussed, in order that it not be required to disclose secret documents in court. Otherwise it would have had to resort to discussing individual passages, which would have been embarrassing. Broadly, the contents would have fallen into five categories: 1) items that were known to be true, and dangerous, such as the accounts of ‘bugging and burgling’ across London; 2) items that were known to be true, but harmless, such as Wright’s description of his early career; 3) items that were known to be untrue, but dangerous, such as Wright’s more outlandish claims about Soviet penetration; 4) items that were untrue, but harmless, such as his account of explaining Blunt’s confession to Tess Rothschild; and 5) items that the authorities were really in the dark about, such as the accusations against Hollis, and MI5’s campaign against Harold Wilson – suspicions of whom, as Wright later admitted, had been harboured only by himself and one other colleague.

The trouble was that Robert Armstrong was ill-equipped to understand the context of any of these issues, and, while his resorting to the ‘too confidential to be discussed’ argument enabled him to conceal his ignorance, the reluctance of the government to enter into any challenges to Wright’s text contributed to the propaganda fall-out. The more energetically that the government tried to ban the book, the more Peter Wright was believed. The fact that the defence had to imply, for legal reasons, that Wright’s allegations were essentially valid, and did not offer any discrimination of them, gave even more power to the ‘Hollis is guilty’ chant.

The most significant item uncovered by Tate is clearly the idea expressed by Armstrong in June 1980 that the government should use Pincher as a way of controlling the narrative. While Charles Moore was allowed to see that memorandum, it was not released until December 2023, as part of PREM 19/591. Moreover, it was of course not divulged to Wright’s legal team, so that Armstrong was able to perjure himself quite shamelessly in the witness-box, claiming that Turnbull’s claims of complicity were just an ‘ingenious conspiracy theory’. Tate covers all this deception in his Epilogue [see below], where he justifiably lambasts the repeat of the policy of selectively releasing sensitive information to certain ‘approved’ writers, and then enforcing some level of control over what they are allowed to say.

It is worth recording some of the most important ‘bootlegged’ findings that, if they had been known at the time of the trial, would have had a very dramatic effect. They include Rothschild’s bid to become intelligence czar, and his discussions with Thatcher on the subject (p 116); the recognition by the Cabinet Office in the summer of 1980 that Rothschild and Wright were already acquainted (p 141); Armstrong’s warnings to Thatcher about being indulgent in allowing former intelligence officers to be indiscreet (p 151); and Thatcher’s subsequent deep concern, in June 1983, about the disclosures. Immediately after the trial, Armstrong started voicing deep concerns that MI5 should be brought under statutory control, and the debates and arguments that followed were heated (pp 275-278). One noticeable exception is the revelation that Armstrong recommended to Thatcher, in June 1980, that Chapman Pincher could be used to defuse the situation: the memorandum was included as part of PREM 19/591, although that file was not declassified until December 2023, which is why the item is such hot news now. Another important item (in PREM 19/1592), which I think Tate overlooks, is the statement made by Sir Anthony Kershaw, the head of the House of Commons Select Committee, in a letter dated November 29, 1986, that the government knew that Wright was the source of information for Pincher’s book. He wrote that two MI5 officers had read the text, and had come to that inescapable conclusion. He thus undermined the case that the government was making about not prosecuting the publishers of TTIT because it appeared not be reliant on an insider source.

The Epilogue

I believe the most significant chapter in the whole book is Tate’s Epilogue, where he describes the scandalous way in which archival material on the ‘Spycatcher’ case has been withheld – but very selectively released to a couple of writers. As stated above, the beneficiaries were Beesley, and Moore, whose Volume 3 of the authorized biography of Margaret Thatcher is the more important. Both writers describe, without any apparent sense of shame or unease, how they were allowed access to papers which had not yet been released to the public, or in fact would never be released at all (or which, individually, were removed from files before they were packaged for declassification, and, in some cases, digitization). What is outrageous, as Tate unequivocally spells out, is that this egregious behaviour is a carbon-copy of the original Thatcher-Armstrong plot. Civil servants have been making judgments about how to propagandize history, and try to ensure that the correct spin is put on events, without any apparent understanding that their highly improper actions would eventually come out in the wash.

Tate uses both Beesley and Moore, although in a rather chaotic and uneven manner. Despite being an ‘Official History’, Beesley’s work has been very poorly edited, with multiple typographical mistakes and a chaotic set of indexes. Beesley is a bit out of his depth in intelligence matters, makes several mistakes in his nomenclature, and fails to gain insights into the intrigues going on. As an example, in his chapter on John Hunt, he fails to make any mention of the coming crisis over Blunt in the late 1970s, where Hunt was intimately involved, an astonishing oversight given the evidence shown in PREM 16/2230. Yet he offers a wide range of items – primarily from ‘Cabinet Office Archives’ (or ‘papers’: the distinction is not clear) and from ‘Prime Minister’s Papers’ – hardly any of which boast an official file identifier, and are referenced solely by date. It is somewhat surprising that Beesley was not able to provide any file numbers, unlike Moore, since their research was roughly contemporaneous. Tate quotes thirty of these items, and they cover an assortment of Armstrong’s and Thatcher’s communications on how to handle the impending crisis, including evidence that Armstrong clearly spoke perjuriously in the witness-box in Australia.

As for Moore, Tate invokes him more cautiously, offering only about a dozen references. Moore, however, does supply file numbers in his supporting Endnotes, and Tate has thus been able to inspect the files that have subsequently been declassified, primarily PREM 19/2506, which was released in December 2023. He claims that he has been able to determine that all the important documents that he cites from Moore have been removed from the relevant file. He is thus dependent upon Moore’s interpretation for what he read, and investigative historians like me cannot verify the sources. (Moore’s Endnotes are dotted with the rubric ‘DCCO’, namely ‘Document Consulted in the Cabinet Office’.) In Moore’s Chapter 8 of Volume 3 (‘Spycatcher: Wright and Wrong’) appear several documents described in this way [see Appendix 2], although it would take another extensive project to discover which of the items in Moore that are not specifically annotated by Tate, but catalogued with a file name (such as PREM 19/591, which was also declassified in December 2023), have been promulgated, and which had been removed beforehand. One very significant item that Moore was allowed to browse – and which he quotes from – is PREM/2500, which covers discussions about the Official Secrets Act, but it is still firmly closed.

I do not believe that all of Tate’s assessments are accurate: for instance, the document described in Note 92 of Chapter 8 in Moore’s book, which is among those that Tate says were removed, appears to exist on page 10 of the digitized version of PREM 19/2006. He makes a reference to Moore’s use of PREM 19/2500 on page 251 of the Thatcher biography, but that file is not listed in the relevant Endnotes. He attributes the reference to Rothschild’s ambitions to lord it over both intelligence services to Moore (p 234), but fails to mention that Moore’s Endnotes indicate that the two items cited came from PREM/2843. The descriptor of that file at TNA indicates that it covers meetings with the heads of the three intelligence services, as well as correspondence with Rothschild. Moore was able to ‘consult’ it, but it has been ‘closed and retained by the Cabinet Office’. This must be one of the most significant partially ‘bootlegged’ files. I thus do not have complete confidence in his process. A rigorous re-evaluation of Moore’s sources needs to be made.

Moore has written a much more engaging book than Beesley’s, and has a sharper nose for the political nuances. Unfortunately, he has also been susceptible to the interview with participants, and Lord Armstrong – as he was when interviewed – was probably as notoriously deceptive in speaking to Moore as he was when appearing in New South Wales. Why should one expect otherwise? And he is also very indulgent with Wright’s character, describing him (in a footnote on page 237) in the following flattering terms: “ . . . his knowledge of the facts was strong, his experience at a senior level in MI5 lengthy and his record of zeal in pursuing treachery unblemished.” In one respect, however, Moore sheds greater light on the machinations behind the dealings with Pincher, when he describes Rothschild’s role. Yet, for some reason, Tate ignores Moore’s very detailed coverage of Rothschild (pp 241-246), where the author, having set up the rather ingenuous statement made by Armstrong to Thatcher in March 1981 that ‘Pincher is known to be acquainted with Lord Rothschild’ (an item acknowledged by Tate), goes on to explore Rothschild’s movements behind the scenes, and his desires to be publicly exonerated.

Moore grasps at Rothschild’s close involvement with the protagonists, but, possibly because of Armstrong’s input, fails to connect the dots. He justifiably raises the important rhetorical question: “If such a person as Lord Rothschild, so close to the world of secrets, had been orchestrating Pincher and Wright to disclose things illegally, why were he and Pincher not being chased by the authorities?”, and goes on to mention the probable conclusion with the government that Christopher Mallaby in the Cabinet Office had pointed out. Yet he fails to drive the point home, leaving the question unanswered, since his primary focus is Thatcher, not the wannabe Spycatcher.

Tate’s studied overlooking of these crucial passages is bizarre, however – almost as if he did not want to undermine his prominent claim that the Wright-Rothschild-Pincher arrangements were coincidental to what Armstrong and Thatcher were plotting. Readers will recall that I recorded two months ago how, according to Bower, both Armstrong and White were convinced that the sick-room adviser to Rothschild had been Maurice Oldfield. Yet the evidence from Moore (including an exchange that the author had with Armstrong) indicates that Rothschild’s introduction of Oldfield into the saga was the first and only time his name had been mentioned. Armstrong apparently did not believe Rothschild’s claim. I suspect, again, that Armstrong was covering up for White. The undeniable fact remains: Armstrong and Thatcher were planning to use Pincher in June 1980, just as the Rothschild-Wright negotiations were about to heat up.

Miscellaneous

I do not like the way that the supportive collateral information has been packaged. I have referred earlier to the arduous exercise of tracing Tate’s connections. It starts with his Endnotes, which lack clear associations with the pages to which they refer. Unlike, say, Andrew’s ‘History’, or Volumes 2 & 3 of Moore’s biography of Thatcher, the Endnotes lack any page header information concerning the pages or chapter to which they refer. I had to inscribe the relevant series of pages at the top of each Endnote page, in order to keep track. When Tate makes a cross-reference to either Beesley or Moore, instead of providing a link to the page number and relevant Endnote number, he simply enters a page number and a date of the minute or letter. Thus I had to turn to the relevant text, take note of the range of Endnote numbers on that page, and check Moore’s and Beesley’s Endnotes to identify the item of interest by its date. All too often, an item for that date could not be found on the page. It seems that the entries were not made by a dedicated professional. All this represents some unnecessary clutter that could have been prevented by the attentions of a qualified Editor.

The ‘Selected Biography’ is very sparse, and while excluding several books mentioned in the Endnotes, does list four volumes written by the notorious fabulist Chapman Pincher. The Endnotes themselves are messy. Apart from the regrettable practice of not providing page numbers above them to guide the reader, the notes themselves are very cluttered, with much repeated information. Each time Beesley’s or Moore’s book appears, for instance, the whole title and publication details appear within the Endnote itself. It is as if the Notes had been prepared by a well-intentioned intern who has not been guided in the correct use of ‘op. cits.’ and ‘ibids.’ The space saved could have been diverted to a structured list of archival sources and descriptions. I created such an inventory myself, finding over forty individual files, or sets of files, that Tate refers to, and which are described on the website of the National Archives. They range from KV (MI5) through HO (Home Office) and FCO (Foreign and Colonial Office) to CAB (Cabinet Office) and PREM (Prime Ministerial) items. A brief description of each would have been invaluable for the occasional researcher: I attach this list as Appendix 1.

Tate’s judgments are sometimes suspect. As I explained in my analysis of his Introduction, I am very critical of his consistent faith in what Wright wrote in his book and in his testimonies. He is in my opinion a bit too trusting of his conversational sources – rather as Moore was with Armstrong – thanking in his ‘Acknowledgements’ Lord Neil Kinnock, Jonathan Aitken and Nigel West, who were all ’refreshingly frank’ about their experiences. He makes an odd judgment that the surveillance of the union leader Jack Jones (who had been in Moscow’s pay, and was later recognized as one of its agents) ‘demonstrated that MI5 had abandoned any pretence of political neutrality’. MI5 did indeed engage in some dubious decisions about perceived threats, but it seems to me that the notion of ‘political neutrality’ should not extend to rejecting surveillance of confirmed subversives intent on overthrowing the constitution. (Jones turned out to be in the pay of the KGB.) He echoes unquestioningly legends such as that of ‘Gibby’s Spy’ (see https://coldspur.com/gibbys-spy/ ), which shows that a reading of coldspur archives might have benefitted him.

The author is rather cavalier about dates. Several times, when I wanted to pinpoint the timing of a statement or event, I turned to his Endnotes only to find that none was offered, and it would require access to Beesley or Moore to discover exactly when the episode occurred. That is a luxury that should not be demanded of curious readers. His style tends to be journalistic and clichéd (especially at the beginning of the book), a characteristic that is shown by the rather melodramatic presentation of personalities involved in the background to this story.

I also believe that he could have exploited to a greater extent recently declassified files. From my initial inspection, they are quite rich, and show the extraordinary lengths to which Armstrong, Thatcher and their minions went to conceal the deceptions, and to spin their messages for outlets such as the House of Commons. Certainly, the PREM 1951-1953 series offers more than appears from Tate’s references, and I judge he could have raided them more deeply instead of relying so heavily on Beesley and Moore. PREM 19/1634, on the Security Commission, and especially the instructions given, in April 1981 – shortly after her statement about the inquiry into Roger Hollis – to Lord Diplock and his team to ‘review security procedures and practices’ is also a very revealing file. Given that the report ascribed the impulse for the inquiry as being the revelations displayed in TTIT by Pincher, and that the Commission had no idea that Thatcher and Armstrong had facilitated that publication, the irony is heavy. Perhaps it was no surprise that the Cabinet Office and the Prime Minister could well have been hoist with their own petard, and did walk into a minefield.

One of the troubling outcomes was another secret story that had been carefully protected. At the time the Security Commission issued its report in December 1981, Robert Armstrong, with some alarm, informed the Prime Minister that, because of the written evidence that Chapman Pincher had given the Commission, it was probable that a person identified as ‘FOLIO’ would soon be exposed. Pincher had claimed to know FOLIO well, and that he had visited him shortly before he died. Armstrong’s hint was that FOLIO was a spy, but Thatcher must have known to whom the Cabinet Secretary was referring. It was certainly Maurice Oldfield, an admitted homosexual who had died in March of that year. (She had been shocked and disbelieving when she learned the truth.) A faint handwritten inscription on Armstrong’s note confirms my conclusion by indicating that the memorandum should be copied to the ‘Oldfield’ file.

Yet the anecdote would reinforce the fact that it would have been very unlikely that Oldfield was the mystery person who had advised Rothschild in hospital, since he had lost his security clearance by then. Tate continues to assert that the ‘former MI6 chief’ was Oldfield, not White. If Tate had inspected Moore’s biography more closely, he would have discovered that another file, PREM 19/2483, also ‘closed’, but to which Moore had access, would show that Oldfield’s homosexual activities had been reported to Thatcher as early as November 1979, and that Thatcher wanted him out of his job by June 1980. By then, Oldfield was already dying from cancer. He would hardly have been in a position to advise Rothschild what action to take on the emerging Wright problem. Furthermore, his reputation would scarcely have been harmed by Rothschild’s naive threat to Armstrong, in January 1987, that he would expose ‘Oldfield’ for conspiratorial work on the Hollis case. He was conveniently dead, and could thus be maligned. On April 23, 1987, Thatcher informed the House of Commons that Oldfield’s security clearance had been cancelled in March 1980 because he had admitted to homosexual activities.

The reason that this possible exposure was embarrassing was the fact that the Commission’s Report had strongly made the point that homosexuals should not be recruited to sensitive government posts because of the risk of blackmail, and the outing of Oldfield would have been a difficult case to explain. (The report had also stressed that, during Positive Vetting, two of the characteristics that should disqualify a candidate were that the subject i) ‘has grossly infringed security regulations’, and ii) ‘has shown himself by act of speech to be unreliable, dishonest, untrustworthy or indiscreet’. Ironically, those exclusions would well apply to Armstrong’s own behaviour through the whole Pincher-Wright-Spycatcher business.) Armstrong also expressed the fear that Pincher might reveal the identity of Oldfield in the coming paperback version of TTIT, showing that he recognized what an unreliable medium the journalist had become. In fact, in the re-issue of TTIT, Pincher was guarded in his references to Oldfield. He did state that, on being posted to Washington, Oldfield had agreed to undertake a CIA polygraph test to confirm that, though a bachelor, he was not a homosexual, and, in his fresh Postscript, Pincher remarked that after Oldfield’s death, MI6 officers had carefully combed his living quarters to look for dangerous evidence. It would have taken a very sharp observer to put two and two together.

The initial leak, as Moore reports, actually came via the editor of the Daily Express, John Junor, who had himself been told by the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir David McNee. It was McNee who had earlier advised the Home Secretary, William Whitelaw, of the evidence found at Oldfield’s flat. Somehow, the actions that MI5 took in confronting Oldfield discouraged Junor from printing anything about the scandal, his rivals did not get wind of it, and Oldfield’s rapidly failing health may have induced a measure of sympathy. Thus the story lay buried for a few years. Whether Rothschild was responsible for the fresh rumours in the press that provoked Thatcher’s statement is another open question. The timing is very provocative, but what Rothschild had to gain from it is obscure, unless it was another collusion between him and Armstrong to distract attention from his role in the Wright business.

I noticed a number of errors that the author might want to correct should the book be considered for a re-print. It should be ‘Richard V. Hall’ (p 371). Auberon Waugh’s article (‘Lord Rothschild is Innocent’) appeared in the Spectator, not in Private Eye (p 354). The biographer of Harold Wilson was Philip ‘Ziegler’, not ‘Zeigler’ (p 347). The reference in Note 19 on p 345 should be to PREM 19/120, not to PREM 19/12. It is ‘Anthony’, not ‘Antony’ Blunt (p 352). On the other hand, it should be ‘Sir Antony Duff’, not ‘Sir Anthony’ (p 380). Victor Rothschild was not recruited by MI5 in the autumn of 1939, and his second wife was an ‘alumna’, not an ‘alumnus’, of Cambridge University (p 61). Tate means ‘orally’, not ‘verbally’ (p 175). The Oxford college should be identified as ‘Christ Church’, not ‘Christ Church college’ (p 213). ‘Peter Wright’s’ appears as ‘Peter Wight’s’ on page 145. In his review of the book in the Times Literary Supplement of September 16 (which I read after completing the first draft of this bulletin) Richard Davenport-Hines points out that Stanley Baldwin was never a member of the Cambridge Apostles (p 46), that David Footman did not study at Oxford in the 1930s (p 63), and that it was Macmillan’s Conservative administration of 1962-63, not Wilson’s Labour government in 1964, which appointed Stuart Hampshire to review the operations of GCHQ (p 62).

Conclusions

The primary message behind Tate’s book, with its subtitle ‘How the Spycatcher Affair Brought M5 in from the Cold’ would appear to suggest that the embarrassing events in Australia were a critical trigger in putting MI5 on a proper statutory footing. Yet that is hardly news: Christopher Andrew’s chapter ‘The Origins of the Security Service Act’ (Section E, Chapter 11) covers the events very logically, and attributes the courtroom debacles as being a strong provocation for such legislation, with Armstrong quickly getting behind the move, and Thatcher eventually being persuaded. Yet, in the promotional description within the covers of the book, this aspect is ignored. The text instead focuses on Peter Wright: “This is the story of Peter Wright’s ruthless and often lawless obsession to uncover Russian spies, both real and imagined, his belated determination to reveal the truth [is there a missing comma here?] and the lengths to which the British government would go to silence him.”

Tate does not deliver on that mission, in my opinion. I see so much tension in the proximity of ‘obsession’, ‘real and imagined’, and ‘reveal the truth’ that cries out for some more profound examination. Until the FLUENCY Committee reports are released, I imagine that a close inspection of the claims of Soviet infiltration will be difficult to assess, but it should be possible to examine more critically the assertions as they are outlined in Spycatcher. I have started that exercise in my analysis of Wright’s double-agents, and of the ELLI controversy, in my debunking of ‘Gibby’s Spy’, and in my comments about the Lonsdale/Cohen case, and I hope some day to pick up the remaining pieces. While Tate has delivered strong and impressive new evidence about the conspiracies and cover-ups within the Cabinet Office, he has carefully avoided tackling the intriguing topic with which his flyleaf entices his readers. He characterizes Wright’s behaviour as ‘obsessive’, but spectacularly fails to analyze how that mania may have affected the accuracy of his accusations.

Another important comment concerns the role of conspiracy theories in intelligence historiography. Christopher Andrew has been quick to deride those unsatisfied by official explanations of puzzling events as ‘conspiracy theorists’ who live in a world unrooted in reality. This saga proves, however, that, when inexplicable events suggest a conspiracy at work, a theory should perhaps be developed for them. That is what Malcom Turnbull did, and challenged Robert Armstrong in court over it. Under oath, Armstrong told Turnbull that his theory was ‘totally untrue’. Baron Armstrong died in 2020: Moore’s devastating description of the deceit appeared in 2019. I wonder whether Armstrong read it, and whether a mischievous civil servant had judged that it was only proper that the secret be leaked before he died . . .

I should also record an important impression. To Catch a Spy led me to reading all three volumes of Moore’s biography, and that exercise clarified for me what enormous pressures Margaret Thatcher was under at the time the ‘Spycatcher’ business required her attention. In her struggles to make her economic policies concerning inflation and the reduction of the annual deficit work, she underwent strong resistance within her own cabinet. She had to deal with militant unions and growing unemployment. There was severe unrest in Northern Ireland, and she faced the ongoing challenge of defining a nuclear defence capability to deter the Soviet Union. It was an enormously onerous time for a new Prime Minister: while she had good instincts, and a solid eye/ear for loose or sloppy thinking, she was not a strategic thinker or a good delegator. Thus I think Robert Armstrong was very foolish to have encouraged her to enter picaresque games with Chapman Pincher. He should have been wise enough to steer her away from such intrigues rather than putting such ideas in her head.

Finally, what about the still unreleased files? In his Epilogue, Tate produced a stirring statement of outrage about the failure of the Cabinet Office to declassify so many important items – including the thirty-two files on the Peter Wright/Spycatcher case. Even Armstrong’s successor, Robin Butler – who declared that he knew what they contained – believes that they should be released. It is difficult to judge how anybody could in this decade be harmed by what they might divulge. Malcolm Turnbull already knows that he was cruelly deceived. The withholding of these important items represents a shocking evasion of responsibility, and a great insult to the intelligence of the public. Someone should make a fresh FOI request for all those items that were exceptionally shown to Charles Moore.

Appendix 1:

Kew Archives referred to by Tate:

Legend: ! = closed; # = declassified; * = digitized

BT 11/2835 # Sale of jet aircraft to Russia

CAB 21/3761 # Publication of Sillitoe’s biography

CAB 21/4971 # Minelaying in the Gulf of Bothnia

CAB 63/192-193 * Hankey’s investigation into Security Service

CAB 164/1870-1901 ! Peter Wright: ‘Spycatcher’ case

CAB 301/30-31 # MI5 Postwar Organizational Issues

CAB 301/270 * John Cairncross

CAB 301/855 # Prime Minister’s 1974 visit to Paris

CAB 301/861 * Allegations about possible coup in 1968

CAB 301/927-2 * Notes on Philby (1967-68)

FCO 30/7004 # European Parliament & ‘Spycatcher’ extracts

FCO 40/2343 # Publication of ‘Spycatcher’ in Hong Kong

FCO 158/28 * Philby (PEACH) File 2

HO 287/145 # Police Pensions

J 157/76 # Attorney-General vs. Newspaper Publishing PLC

KV 2/1420-1428 * Gouzenko

KV 2/4607-4608 * Goronwy Rees

KV 2/4393-4397 # Flouds

KV 2/1543-1544 # Clarks

KV 2/1555 * Cockburn

KV 2/1636-1646 * Marshall

KV 2/3030-3031 * Zuckerman

KV 2/3221-3222 * Bernstein

KV 2/3444- 3448 * Petrovs

KV 2/3993-3995 # Dewick

KV 2/4531-4534 * Rothschilds

KV 2/4601 * Rudolf Katz

KV 4/88 # Petrie’s 1941 Report on MI5

KV 4/466-467 * Liddell’s Diaries

PREM 11/2800 # 1959 leak on space research

PREM 16/2230 # PM briefings on Blunt

PREM 16/2230-1 ! Notes to briefings on Blunt

PREM 19/120 # Blunt and Security

PREM 19/120-1 ! Notes to Blunt and Security [open 2032]

PREM 19/591 * ‘Their Trade is Treachery’

PREM 19/918 ! Activities of Leo Long

PREM 19/1621 ! Publication of book by Bloch and Fitzgerald

PREM 19/1634 # Review by Security Commission

PREM 19/1951-1953 * ‘Their Trade is Treachery’ & Hollis

PREM 19/2500 ! Reform of Official Secrets Act

PREM 19/2504-2511 * ‘Their Trade is Treachery’ & Wright

PREM 19/3942 * Blunt & Home Affairs Select Committee

Appendix 2:

Moore’s DCCO Sources in ‘Spycatcher: Wright or wrong’

Additional Legend: % cited material removed before release (acc. Tate)

PREM 19/591 *%

PREM 19/1951 *%

PREM 19/1952 *

PREM 19/1953 *

PREM 19/1954 *% John Bettaney

PREM 19/2074 ! Defence: Zircon satellite Project Part 1

PREM 19/2483 ! Security: Sir Maurice Oldfield

PREM 19/2500 ! OSA [cited erroneously by Tate]

PREM 19/2505 *

PREM 19/2506 *%

PREM 19/2507 *

PREM 19/2508 *

PREM 19/2509 *

PREM 19/2510 *

PREM 19/2843 ! Security: Prime Minister’s Briefing

PREM 19/3530 ! Reform of OSA: Part 3

Appendix 3:

Directors General of MI5

1941-1946 David Petrie

1946-1953 Percy Sillitoe

1953-1956 Dick White

1956-1965 Roger Hollis

1965-1972 Martin Furnival-Jones

1972-1978 Michael Hanley

1978-1981 Howard Smith

1981-1985 John Jones

1985-1988 Antony Duff

1988-1992 Patrick Walker

Appendix 4:

Prime Ministers

1945-1951 Clement Attlee

1951-1955 Winston Churchill

1955-1957 Anthony Eden

1957-1963 Harold Macmillan

1963-1964 Alec Douglas-Home

1964-1970 Harold Wilson

1970-1974 Edward Heath

1974-1976 Harold Wilson

1976-1979 James Callaghan

1979-1990 Margaret Thatcher

Appendix 5:

Cabinet Secretaries

1947-1962 Norman Brook

1963-1973 Burke Trend

1973-1979 John Hunt

1979-1987 Robert Armstrong

1987-1997 Robin Butler

Appendix 6:

Chiefs of MI6

1939-1952 Stewart Menzies

1953-1956 John Sinclair

1956-1968 Dick White

1968-1973 John Rennie

1973-1978 Maurice Oldfield

1979-1982 Arthur (‘Dicky’) Frank

1982-1985 Colin Figures

1985-1989 Chris Curwen

Appendix 7:

Attorneys General

1945-1951 Hartley Shawcross

1951-1951 Frank Soskice

1951-1954 Lionel Heald

1954-1962 Reginald Manningham-Buller

1962-1964 John Hobson

1964-1970 Elwyn Jones

1970-1974 Peter Rawlinson

1974-1979 Samuel Silkin

1979-1987 Michael Havers

1987-1992 Patrick Mayhew

Appendix 8:

Home Secretaries

1940-1945 Herbert Morrison

1945-1945 Donald Sorrell

1945-1951 James Chuter Ede

1951-1954 David Maxwell Fyfe

1954-1957 Gwilym Lloyd George

1957-1962 Rab Butler

1962-1964 Henry Brooke

1964-1965 Frank Soskice

1965-1967 Roy Jenkins

1967-1970 James Callaghan

1970-1972 Reginald Maudling

1972-1974 Robert Carr

1974-1976 Roy Jenkins

1976-1979 Merlyn Rees

1979-1983 William Whitelaw

1983-1965 Leon Brittan

1985-1989 Douglas Hurd

1989-1990 David Waddington

Appendix 9:

Foreign Secretaries

1940-1945 Anthony Eden

1945-1951 Ernest Bevin

1951-1951 Herbert Morrison

1951-1955 Anthony Eden

1955-1955 Harold Macmillan

1955-1960 Selwyn Lloyd

1960-1963 Alec Douglas-Home

1963-1964 Rab Butler

1964-1965 Patrick Gordon Walker

1965-1966 Michael Stewart

1966-1968 George Brown

1968-1970 Michael Stewart

1970-1974 Alec Douglas-Home

1974-1976 James Callaghan

1976-1977 Anthony Crosland

1977-1979 David Owen

1979-1982 Peter Carrington

1982-1983 Francis Pym

1983-1989 Geoffrey Howe

1989-1989 John Major

1989-1995 Douglas Hurd

(Latest Commonplace entries can be seen here.)

I rather suspected Tony with your deep knowledge of these matters you would find flaws aplenty among the wheat that has been cultivated by Tim Tate. The idea that Peter Wright himself was suspect ie the Fifth Man (or whatever) I only recall reading in print once, and this was in the autobiography of the theatre and film director Richard Eyre who among other works made the controversial film Tumbledown. He reported dining with a senior Tory Party fixer who was allied to Thatcher and had connections to the Security Services (sorry I forget the name which rather spoils the flow here) and who died some years ago – I recall the obituary of the man in a national newspaper. Anyway this chap said to Eyre the Spycatcher case all makes sense when you realise Wright was the Fifth Man. I don’t think Eyre knew what to make of this assertion. I’ve not ever believed there’s much of a case that Wright was dodgy but in that world who knows. One wonders alternatively if this was actually a disinformation exercise to try to undermine Wright. Rumour mongering was/is obviously a stock in trade for the security deep state – I rather suspect my adoptive father in the course of his work with the UKAEA may have had cause to practice these darks arts. As for John Junor I wish I could recall the TV program where he was interviewed and made a joke a bit of the notion that the papers published the truth. I’m wondering if it was in connection with the Kray case where the core truth was buried that they were providing rent boys to Tory establishment figures like Lord Boothby. But it may have been something else. Left you in no doubt Junor knew many secrets…..

Ha! (Thanks, David.) Wright could have hardly been the ‘Fifth Man’ if Cairncross already had claims to the post, and I am sure he was never recruited by the KGB as one of what Andrew tastelessly describes as the ‘Magnificent Five’, but what Eyre’s friend said closely matches what Cyril Mills claimed – that Wright was the real traitor. What Wright, Martin, de Mowbray and White did in undermining morale in MI5 was more harmful than anything the KGB achieved, in my opinion.

Tony.