I was reading, in the Times Literary Supplement of January 17, a review of a book titled The French Revolutionary Tradition in Russian and Soviet Politics, Political Thought, and Culture. The author of the book was one Jay Bergman, the writer of the review Daniel Beer, described as Reader in Modern European History at Royal Holloway, University of London. I came across the following sentences: “The Bolsheviks could never admit that Marxism was a failed ideology or that they had actually seized power in defiance of it. Their difficulties, they argued, were rather the work of enemies arrayed against the Party and traitors in their midst.”

This seemed to me an impossibly quaint way of describing the purges of Stalin’s Russia. Whom were these Bolsheviks trying to convince in their ‘arguments’, and where did they make them? Were they perhaps published on the Letters page of the Pravda Literary Supplement or as articles in The Moscow Review of Books? Or were they presented at conferences held at the elegant Romanov House, famed for its stately rooms and its careful rules of debate? I was so taken aback by the suggestion that the (unidentified) Bolsheviks had engaged in some kind of serious discussions on policy, as if they were an Eastern variant of the British Tory Party, working through items on the agenda at some seaside resort like Scarborough, and perhaps coming up with a resolution on the lines of tightening up on immigration, that I was minded to write a letter to the Editor. It was short, and ran as follows:

“So who were these Bolsheviks who argued that ‘their difficulties were rather the work of enemies arrayed against the Party and traitors in its midst’? Were they perhaps those ‘hardliners in the Politburo’ whom Roosevelt, Churchill and Eden imagined were exerting a malign influence on the genial Uncle Joe Stalin, but whose existence turned out to be illusory? Or were they such as Trotsky, Kirov, Radek, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Bukharin, etc. etc., most of whom Stalin had murdered simply because they were ‘old Bolsheviks’, and knew too much? I think we should be told.”

Now the Editor did not see fit to publish my offering. Perhaps he felt that, since he had used a letter of mine about the highly confused Professor Paul Collier in the December 2019 issue, my quota was up for the season. I can think of no other conceivable reason why my submission was considered of less interest than those which he did select.

Regular readers of coldspur will be familiar with my observations about the asymmetry of Allied relationships with the Soviet Union in World War II. See, for instance, https://coldspur.com/krivitsky-churchill-and-the-cold-war/, where I analysed such disequilibrium by the categories of Moral Equivalency, Pluralism vs. Totalitarianism, Espionage, Culture, and Warfare. The misunderstanding about the nature of Stalin’s autocracy can be viewed in two dimensions: the role of the Russian people, and that of Stalin himself.

During the war, much genuine and well-deserved sympathy was shown in Britain towards the long-suffering Russian people, but the cause was often distorted by Soviet propaganda, either directly from such as ambassador Maisky and his cronies, or by agents installed in institutions such as the Ministry of Information. The misconceptions arose from thinking that the Russians were really similar to British citizens, with some control over their lives, where they worked, the selection of those who governed them, what they could choose to read, how they were allowed to congregate and discuss politics, and the manner in which they thus influenced their leaders, but had unfortunately allowed themselves to sign a pact with the Nazis and then been treacherously invaded by them. Their bravery in defending their country against the assault, with losses in the millions, was much admired.

Yet the catastrophe of Barbarossa was entirely Stalin’s fault: as he once said to his Politburo, using a vulgar epithet, ‘we’ had screwed up everything that Lenin had founded and passed on. And he was ruthless in using the citizenry as cannon fodder, just as he had been ruthless in sending innocent victims to execution, famine, exile, or the Gulag. For example, in the Battle of Stalingrad, 10,000 Soviet soldiers were executed by Beria’s NKVD for desertion or cowardice in the face of battle. 10,000! It is difficult to imagine that number, but I think of the total number of pupils at my secondary school, just over 800, filling Big School, and multiplying it by 12. If anything along those lines had occurred with British forces, Churchill would have been thrown out in minutes. Yet morale was not universally sound with the Allies, either. Antony Beevor reports that in May 1944 ‘nearly 30,000 men had deserted or were absent without leave from British units in Italy’ – an astonishing statistic. The British Army had even had a mutiny on its hands at Salerno in 1943, but the few death sentences passed were quickly commuted. (Stalin’s opinions on such a lily-livered approach to discipline appear not to have been recorded.) As a reminder of the relative casualties, the total number of British deaths in the military (including POWs) in World War II was 326,000, with 62,000 civilians lost. The numbers for the Soviet Union were 13,600,000 and 7,000,000, respectively.

As my letter suggested, Western leaders were often perplexed by how Stalin’s occasionally genial personality, and his expressed desire for ‘co-operation’, were frequently darkened by influences that they could not discern. They spoke (as The Kremlin Letters reminds us) of Stalin’s need to listen to public opinion, or deal with the unions, or heed those hard-liners on the Politburo, who were all holding him back from making more peaceful overtures over Poland, or Italy, or the Baltic States. During negotiations, Molotov was frequently presented as the ‘hard man’, with Stalin then countering with a less demanding offer, thus causing the Western powers to think they had gained something. This was all nonsense, of course, but Stalin played along, and manipulated Churchill and Roosevelt, pretending that he was not the despot making all the decisions himself.

Thus Daniel Beer’s portrayal of those Bolsheviks ‘arguing’ about the subversive threat holds a tragi-comic aspect in my book. Because those selfsame Bolsheviks who had rallied under Lenin to forge the Revolution were the very same persons whom Stalin himself identified as a threat to him, and he had them shot, almost every one. The few that survived did so because they were absolutely loyal to Stalin, and not to the principles (if they can be called that) of the Bolshevik Revolution.

I was reminded of this distortion of history when reading Professor Sir Michael Howard’s memoir, Captain Professor. I had read Howard’s obituary in December 2019, and noted from it that he had apparently encountered Guy Burgess when at Oxford. The only work of Howard’s that I had read was his Volume 5 of the History of British Intelligence in the Second World War, where he covered Strategic Deception. (The publication of this book had been delayed by Margaret Thatcher, and its impact had thus been diminished by the time it was issued in 1999. I analysed it in my piece ‘Officially Unreliable’. It is a very competent but inevitably flawed analysis of some complex material.) With my interest in Burgess’s movements, and his possible involvement in setting up the ‘Oxford Ring’ of spies, I wanted to learn more about the timing of this meeting, and what Burgess was up to, so I acquired a copy of Howard’s memoir.

The paragraph on Burgess was not very informative, but I obviously came to learn more about Howard, this acknowledged expert in the history of warfare. He has received several plaudits since his death. In the January issue of History Today, the editor Paul Lay wrote an encomium to him, which included a quotation from the historian’s essay ‘Military Experience in European Literature’. It ran as follows: “In European literature the military experience has, when it has been properly understood and interpreted, immeasurably enriched that understanding of mankind, of its powers and limitations, of its splendours and its miseries, and not least of its relationship to God, which must lie at the root of all societies that can lay any claim to civilization.”

Now what on earth does that mean? I was not impressed by such metaphysical waffle. If I had submitted a sentence like that in an undergraduate essay, I would not have been surprised to see it returned with a circle of red ink. Yet its tone echoed a remark by Howard, in Captain Professor, that I had included in my December 2019 Commonplace file: “I had written a little about this in a small book The Invention of Peace, a year earlier, where I tried to describe how the Enlightenment, and the secularization and industrialization it brought in its wake, had destroyed the beliefs and habits that had held European society together for a thousand years and evoked a backlash of tribal nationalism that had torn apart and reached climax with the two world wars.” (p 218) Hallo, Professor! ‘Beliefs and habits that had held European society together for a thousand years’? What about all those wars? Revolutions? Religious persecution? Specifically, what about the Inquisition and the Thirty Years War? What was this ‘European society’ that cohered so closely, and which the Professor held in such regard? I wondered whether the expression of these somewhat eccentric ideas was a reason why the sometime Regius Professor of History at Oxford University had not been invited to contribute to the Oxford Illustrated History of Modern War, or the Oxford Illustrated History of World War II.

Apparently, all this has to do with the concept of ‘War and Society’, with which Howard is associated. Another quote from Captain Professor: “The history of war, I came to realize, was more than the operational history of armed forces. It was the study of entire societies. Only by studying their cultures could one come to understand what it was they fought about and why they fought in the way they did. Further, the fact that they did so fight had a reciprocal impact on their social structure. I had to learn not only to think about war in a different way, but also to think about history itself in a different way. I would certainly not claim to have invented the concept of ‘War and Society’, but I think I did something to popularize it.” Note the contradiction that, if these ‘societies and cultures’ were fighting each other, they could hardly be said to have ‘held together for a thousand years’. I am also not sure that the Soviet soldiers in WII, conscripted and harassed by the NKVD, shot at the first blink of cowardice or retreat, thought much about how the way they fought had a reciprocal impact on Soviet culture (whatever that was), but maybe Howard was not thinking of the Red Army. In some sense I could see what he was getting at (e.g. the lowering of some social barriers after World War II in the United Kingdom, because of the absurd ‘officers’ and ‘men’ distinctions: no one told me at the time why the Officers’ Training Corps had morphed into the Combined Cadet Force). Nevertheless, it seemed a bizarre agenda.

And then I came on the following passage, describing Howard’s experiences in Italy: “In September 1944, believing that the end of the war was in sight, the Allied High Command had issued orders for the Italian partisans to unmask themselves and attack German communications throughout the north of Italy. They did so, including those on and around Monte Sole. The Germans reacted with predictable savagery. The Allied armies did not come to their help, and the partisan movement in North Italy was largely destroyed. It was still believed – and especially in Bologna, where the communists had governed the city ever since the war – that this had been deliberately planned by the Allies in order to weaken the communist movement, much as the Soviets had encouraged the people of Warsaw to rise and then sat by while the Germans exterminated them. When I protested to my hosts that this was an outrageous explanation and that there was nothing that we could have done, they smiled politely. But I was left wondering, as I wondered about poor Terry, was there really nothing that we could have done to help? Were there no risks that our huge cumbrous armies with their vast supply-lines might have taken if we knew what was going on? – and someone must have known what was going on. Probably not: but ever since then I have been sparing of criticism of the Soviet armies for their halt before Warsaw.”

My initial reaction was of astonishment, rather like Howard’s first expression of outrage, I imagine. How could the betrayal of the Poles by the halted Soviet forces on the banks of the Vistula, in the process of ‘liberating’ a country that they had raped in 1939, now an ally, be compared with the advance of the Allied Armies in Italy, trying to expel the Germans, while liberating a country that had been an enemy during the war? What had the one to do with the other? And why would it have been controversial for the Allies to have wanted to weaken the Communist movement? But perhaps I was missing something. What had caused Howard to change his mind? I needed to look into it.

The poignant aspect of this anecdote was that Howard had been wounded at Monte Sole, only in December 1944, some two months after the Monte Sole massacre. Howard had been commanding a platoon, and had been sent on a reconnaissance mission with ‘poor Terry’ (an alias). Returning from the front line, they had become disoriented, and stumbled into an ambush, where Terry was mortally wounded by a mine, and Howard, having been shot in the leg, managed to escape. He was mortified by the fact that he had chosen to leave Terry to die, and felt his Military Cross was not really deserved. He had fought courageously for the cause of ridding Italy of fascism, yet the fact that he had not known at the time of the Massacre of Monte Sole (sometimes known as the Marzobotto Massacre) was perplexing to me.

These two closely contemporaneous events – the Warsaw Uprising, and the Monte Sole Massacre – were linked in a way that Howard does not describe, as I shall show later. They could be summarised as follows:

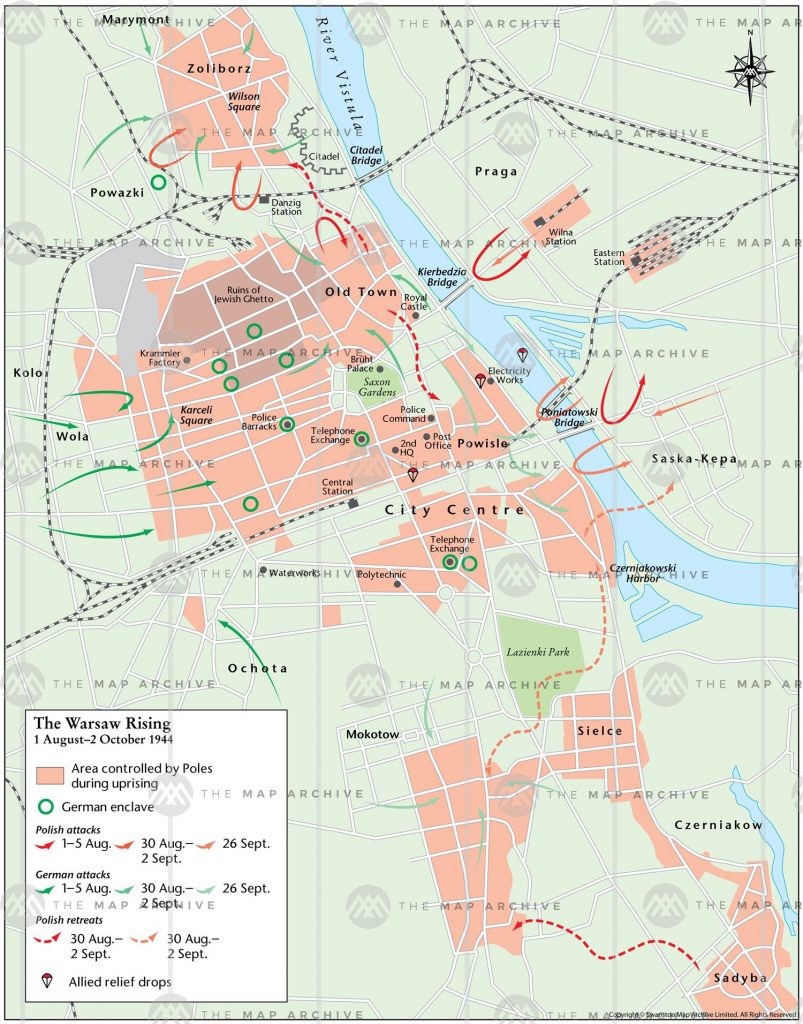

The Warsaw Uprising

As the Red Army approached Warsaw at the end of July of 1944, the Polish government-in-exile in London decided that it needed to install its own administration before the Communist Committee of National Liberation, established by the Soviets as the Lublin Committee on July 22, could take over leadership. Using its wireless communications, it encouraged the illegal Polish military government in Warsaw to call on the citizenry to build fortifications. On July 29, the London leader, Mikolajczyk, went to Moscow, whereupon Moscow Radio urged the Polish Resistance to rise up against the invader. A few days later, Stalin promised Mikołajczyk that he would assist the Warsaw Uprising with arms and ammunition. On August 1, Bor-Komorowski, the Warsaw leader, issued the proclamation for the uprising. In a few days, the Poles were in control of most of Warsaw, but the introduction of the ruthless SS, under the leadership of von dem Bach-Zelewski, crushed the rebellion with brutal force. Meanwhile, the Soviets waited on the other side of the Vistula. Stalin told Churchill that the uprising was a stupid adventure, and refused to allow British and American planes dropping supplies from as far away as Italy to land on Soviet territory to refuel. The resistance forces capitulated on October 2, with about 200,000 Polish dead.

The Monte Sole Massacre

In the summer of 1944, British and American forces were making slow progress against the ‘Gothic Line’, the German defensive wall that ran along the Apennines. Italy was at that time practically in a stage of civil war: Mussolini had been ousted in the summer of 1943, and Marshall Badoglio, having signed an armistice with the Allies, was appointed Prime Minister on September 3. Mussolini’s RSI (the Italian Social Republic) governed the North, as a puppet for the Germans, while Badoglio led the south. Apart from the general goal of pushing the Germans out of Italy, the strategic objective had been to keep enough Nazi troops held up to allow the D-Day invasion of Normandy to take place successfully. In late June, General Alexander appealed to the Italian partisans to intensify a policy of sabotage and murder against the German forces. The Germans already had a track-record of fierce reprisals, such as the Massacre at the Ardeatine Caves in Rome in March 1944, when 320 civilians had been killed following the murder of 32 German soldiers. The worst of these atrocities occurred at Monte Sole on September 29-30, where the SS killed 1830 local villagers at Marzabotto. Shortly after that, Alexander called upon the partisans to hold back their assaults because of the approach of winter.

Now, there are some obvious common threads woven into these narratives (‘partisans’, ‘reprisals’, ‘invasions’, ‘encouragement’, ‘SS brutality’, ‘betrayal’), but was there more than met the eye, and was Howard pointing at something more sinister on the part of the Western Allies, and something more pardonable in the actions of the Soviets? I needed some structure in which to shape my research, if I were to understand Howard’s weakly presented case. Thus I drew up five categories by which I could analyse the events:

- Military Operation: What was the nature of the overall military strategy, and how was it evolving across different fronts?

- Political Goals: What were the occupier’s (‘liberator’s’) goals for political infrastructure in the territories controlled, and by what means did they plan to achieve them?

- Make-up, role and goals of partisans: How were the partisan forces constituted, and what drove their activities? How did the respective Allied forces communicate with, and behave towards, the partisan forces?

- Offensive strategy: What was the offensive strategy of the armed forces in approaching their target? How successful was the local operation in contributing to overall military goals?

- The Aftermath, political outcomes and historical assessment: What was the long-term result of the operation on the country’s political architecture? How are the events assessed seventy-five years later?

The Red Army and Warsaw

- Military Operation:

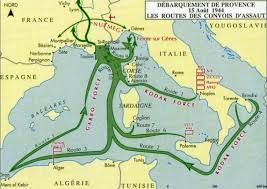

The most important resolution from the Tehran Conference, signed by Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin on December 1, 1943, was a co-ordinated approach to ensuring that the planned D-Day operation (‘Overlord’) would be complemented by assaults elsewhere. Such cooperation would prevent German forces being withdrawn to defend the Allies in eastern France. Thus an operation in the South of France (‘Anvil’) was to take place at the same time that Stalin would launch a major offensive in the East (‘Bagration’). At that time Overlord was planned to occur in late May; operational problems, and poor weather meant that it did not take place until June 6, 1944.

Stalin’s goal was to reach Berlin, and conquer as much territory as he could before the Western Allies reached it. Ever since his strategy of creating ‘buffer states’ in the shape of eastern Poland, the Baltic States, and western Ukraine after the Nazi-Soviet pact of August 1939 had been shown to be an embarrassing calamity (although not recognized by Churchill at the time), he realised that more vigorously extending the Soviet Empire was a necessity for spreading the cause of Bolshevism, and protecting the Soviet Union against another assault from Germany. When a strong defensive border (the ‘Stalin Line’) had been partially dismantled to create a weaker set of fortifications along the new borders with Nazi Germany’s extended territories (the ‘Molotov Line’), it had fearfully exposed the weaknesses of the Soviet armed forces, and Hitler had invaded with appalling loss of life and material for the Soviet Union.

In 1944, therefore, the imperative was to move forward ruthlessly, capturing the key capital cities that Hitler prized so highly, and pile in a seemingly inexhaustible supply of troops. When the Red Army encountered German forces, it almost always outnumbered them, but the quality of its leadership and personnel were inferior, with conscripts often picked up from the territories gained, poorly trained, but used as cannon fodder. Casualties as a percentage of personnel were considerably higher than that which the Germans underwent. The Soviet Union had produced superior tanks, but repair facilities, communications, and supply lines were constantly being stretched too far.

On June 22, Operation ‘Bagration’ began. Rokossovsky’s First Belorussian Front crossed the River Bug, which was significantly on the Polish side of the ‘Curzon Line’, the border defined (and then modified by Lewis Namier) in 1919, but well inside the expanded territories of Poland that the latter had occupied and owned between the two World Wars. On July 7, Soviet troops entered Vilna to the north, a highly symbolic city in Poland’s history. On July 27, they entered Bialystok and Lvov. By July 31, they had approached within twenty-five miles of the Vistula, the river that runs through Warsaw, and four days later, had actually crossed the waterway 120 miles south of Warsaw. At this stage, exhausted and depleted, they met fiercer opposition from German forces. Exactly what happened thereafter is a little murky.

- Political Goals:

The Soviets’ message was one of ‘liberation’, although exactly from what the strife-worn populations of the countries being ‘liberated’ were escaping from was controversial. The Baltic States (Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia) had suffered, particularly, from the Soviet annexation of 1940, which meant persecution and murder of intellectuals and professionals, through the invasion by Nazi forces in the summer of 1941, which meant persecution and murder of Jews and Communists, to the re-invasion of the Soviets in 1944, which meant persecution and murder of anyone suspected of fascist tendencies or sympathies. Yet the British Foreign Office had practically written off the Baltic States as a lost cause: Poland was of far greater concern, since it was on her behalf that Great Britain had declared war on Germany in September 1939.

The institution favoured by the British government to lead Poland after the war was the government-in-exile, led, after the death in a plane crash of General Sikorski in June 1943, by Stanisław Mikałojczyk. It maintained wireless communications with underground forces in Poland, but retained somewhat unreasonable goals for the reconstitution of Poland after the war, attaching high importance to the original pre-war boundaries, and especially to the cities of Vilna and Lvov. The London Poles had been infuriated by Stalin’s cover-up of the Katyn massacres, and by Churchill’s apparent compliance, the British prime Minster harbouring a desire to maintain harmonious relations with Stalin. Mikałojczyk continuously applied pressure on Winston Churchill to represent the interests of a free and independent Poland to Stalin, who, like Roosevelt, had outwardly accepted the principles of the Atlantic Charter that gave the right of self-determination to ‘peoples’. Mikałojczyk was adamant on two matters: the recognition of its traditional eastern borders, and its right to form a non-communist government. Stalin was equally obdurate on countering both initiatives, and his language on a ‘free and independent Poland’ started taking on clauses that contained a requirement that any Polish government would have to be ‘friendly’ towards the Soviet Union.

On July 23, the city of Lublin was liberated by the Russians, and Stalin announced that a Polish Committee of National Liberation (the PCNL, a communist puppet) had been set up in Chelm the day before. Churchill was in a bind: he realised which way the wind was blowing, and how Soviet might would determine the outcomes in Poland. He desperately did not want to let down Mikałojczyk, and preferred, foolishly, to trust in Stalin’s benevolence and reasonableness. Churchill had been pressing for Mikałojczyk to meet with Stalin, as he was beginning to become frustrated by the Poles’ insistence and romantic demands. Stalin told Churchill that Mikałojczyk should confer with the PCNL.

When Stalin made an ominously worded declaration on July 28, where he ‘welcomed unification of Poles friendly disposed to all three Allies’ (which made even Anthony Eden recoil in horror), Churchill convinced Mikałojczyk to visit Moscow, where Stalin agreed to see him. On July 29, Moscow Radio urged the workers of the Polish Resistance to rise up against the German invader. Had Mikałojczyk perhaps been successful in negotiating with Stalin?

- The Partisans:

On July 31, the Polish underground, encouraged by messages from the Polish Home Army in London, ordered a general uprising in Warsaw. It had also succeeded in letting a delegate escape to the USA and convince the US administration that it could ally with Soviet forces in freeing Warsaw. (It is a possibility that this person, Tatar, was a Soviet agent: something hinted at, but not explicitly claimed, by Norman Davies.) It was, however, not as if there was much to unite the partisans, outside a hatred of the Fascist occupying forces. The Home Army (AK) was threatened by various splinter groups, namely the People’s Army (AL), which professed vague left-wing political opinions (i.e. a removal of the landowning class, and more property rights for small farmers and peasants), the PAL, which was communist-dominated, and thus highly sympathetic to the Soviet advance, and the Nationalist Armed Forces (NSZ), which Alan Clark described as ‘an extreme right-wing force, against any compromise with Russian power’. Like any partisan group in Europe at the time, it was thus driven by a mixture of motivations.

Yet for a few short weeks they unified in working on fortifications and attacking the Nazis. They mostly took their orders from London, but for a short while it seemed that Moscow was supporting them. According to Alexander Werth (who was in Warsaw at the time), there was talk in Moscow that Rokossovsky would shortly be capturing Warsaw, and Churchill was even spurred to remind the House of Commons on August 2 of the pledge to Polish independence. On August 3, Stalin was reported by Mikałojczyk to have promised to assist the Uprising by providing arms and ammunition – although the transcripts of their discussions do not really indicate this. By August 6, the Poles were said (by Alan Clark) to be in control of most of Warsaw.

The Home Army was also considerably assisted by Britain’s Special Operations Executive, which had succeeded in landing hundreds of agents in Warsaw and surrounding districts, with RAF flights bringing food, medical supplies and wireless equipment. This was an exercise that had started in February 1941, with flights originating both from Britain and, latterly, from southern Italy. By the summer of 1944, a majority of the military and civilian leadership in Warsaw had been brought in by SOE. Colonel Gubbins, who had been appointed SOE chief in September 1943, was an eager champion of the Polish cause, but the group’s energies may have pointed to a difference in policy between SOE’s sabotage programme, and Britain’s diplomatic initiatives, a subject that has probably not received the attention it merits.

Yet the Rising all very quickly turned sour. The Nazis, recognizing the symbolic value of losing an important capital city like Warsaw, responded with power. The Hermann Goering division was rushed from Italy to Warsaw on August 3. Five days later the SS, led by von dem Bach-Zelewski, was introduced to bring in a campaign of terror against the citizenry. After a desperate appeal for help by the beleaguered Poles to the Allies, thirteen British aircraft were despatched from southern Italy to drop supplies: five failed to return. The Chiefs of Staff called off the missions, but a few Polish planes carried on the effort. Further desperate calls for help arrived, and on August 14 Stalin was asked to allow British and American planes, based in the UK, to refuel behind the Soviet lines to allow them more time to focus on airdrops. He refused.

By now, however, Stalin was openly dismissing the foolish adventurism of the Warsaw Uprising, lecturing Churchill so on August 16, and, despite Churchill’s continuing implorations, upgraded his accusations, on August 23, to a claim that the partisans were ‘criminals’. On August 19, the NKVD had shot several dozen members of the Home Army near the Byelorussian border, carrying out an order from Stalin that they should be killed if they did not cooperate. Antony Beevor states that the Warsaw Poles heard about that outrage, but, in any case, by now the Poles in London were incensed to the degree that they considered Mikałojczyk not ‘anti-Soviet’ enough. Roosevelt began to tire of Churchill’s persistence, since he was much more interested in building the new world order with Uncle Joe than he was in sorting out irritating rebel movements. By September 5, the Germans were in total control of Warsaw again, and several thousand Poles were shot. On September 9, the War Cabinet had reluctantly concluded that any further airdrops could not be justified. The Uprising was essentially over: more than 300,000 Poles lost their lives.

- Offensive Strategy:

Accounts differ as to how close the Soviet forces were to Warsaw, and how much they were repulsed by fresh German attacks. Alexander Werth interviewed General Rokossovsky on August 26, 1944, the latter claiming that his forces were driven back after August 1 by about 65 miles. Stalin told Churchill in October, when they met in Moscow, of Rokossovsky’s tribulations with fresh German attacks. Yet that does not appear to tally with Moscow’s expectations for the capture of Warsaw, and it was a surprising acknowledgement of weakness on Rokossovsky’s part if it were true. Soviet histories inform us that the thrust was exhausted by August 1, but, in fact, the First Belorussian Front was close to the suburb of Praga by then, approaching from the south-east. (The Vistula was narrower than the Thames in London. I was about to draw an analogy of the geography when I discovered that Norman Davies had beaten me to it, using almost the exact wording that I had thought suitable: “Londoners would have grasped what was happening if told that everyone was being systematically deported from districts north of the Thames, whilst across the river to Battersea, Lambeth, and Southwark nothing moved, no one intervened,” from Rising ’44, page 433). Rokossovsky told Werth that the Rising was a bad mistake, and that it should have waited until the Soviets were close. On the other hand, the Polish General Anders, very familiar with Stalin’s ways, and then operating under Alexander in Italy, thought the Uprising was a dangerous mistake.

Yet all that really misses the point. It was far easier for Stalin to have the Germans exterminate the opposition, even if it contained some communist sympathisers. (Norman Davies hypothesizes that the radio message inciting the partisans to rebel may have been directed at the Communists only, but it is hard to see how an AL-only uprising would have been able to succeed: such a claim sounds like retrospective disinformation.) Stalin’s forces would eventually have taken over Warsaw, and he would have conducted any purge he felt was suitable. He had shamelessly manipulated Home Army partisans when capturing Polish cities to the east of Warsaw (such as Lvov), and disposed of them when they had delivered for him. Thus sitting back and waiting was a cynical, but reasonable, strategy for Stalin, who by now was confident enough of his ability to execute – and was also being informed by his spies of the strategies of his democratic Allies in their plans for Europe. Donald Maclean’s first despatch from the Washington Embassy, betraying communications between Churchill and Roosevelt, was dated August 2/3, as revealed in the VENONA decrypts.

One last aspect of the Soviet attack concerns the role of the Poles in the Red Army. When the captured Polish officers who avoided the Katyn massacres were freed in 1942, they had a choice: to join Allied forces overseas, or to join the Red Army. General Zygmunt Berling had agreed to cooperate after his release from prison, and had recommended the creation of a Polish People’s Army in May 1943. He became commander of the first unit, and eventually was promoted to General of the Polish Army under Rokossovsky. But it was not until August 14 that he was entrusted to support the Warsaw Uprising, crossing the Vistula and entering Praga the following day – which suggests that the river was not quite the natural barrier others have made it out to be. He was repulsed, however, and had to withdraw eight days later. The failed attempt, with many casualties, resulted in his dismissal soon afterwards. Perhaps Stalin felt that Polish communists, because they were Poles, could be sacrificed: Berling may not have received approval for his venture.

- The Aftermath:

With Warsaw untaken, the National Council of Poland declared Lublin as the national capital, on August 18, and on September 9, a formal agreement was signed between the Polish communists and the Kremlin. In Warsaw, Bach-Zelewski, perhaps now concluding that war crimes trials might be hanging over him, relented the pressure somewhat, and even parleyed with the survivors. He tried to convince them that the threat from Bolshevism was far more dangerous than the continuance of Fascism, even suggesting that the menace from the East ‘‘might very well bring about the downfall of Western culture’ (Clark). It was not certain what aspects of Western culture he believed the Nazi regime had enhanced. (Maybe Professor Howard could have provided some insights.)

The Lublin administration had to wait a while as the ‘government-in-waiting’, as Warsaw was not captured by the Red Army until January 17, 1945. By that time, imaginative voices in the Foreign Office had begun to point out the ruthlessness and menace of the tide of Soviet communism in eastern Europe, and Churchill’s – and even more, Roosevelt’s – beliefs that they could cooperate with the man in the Kremlin were looking very weary. By the time of the Yalta conference in February 1945, any hopes that a democratically elected government would take power in Poland had been abandoned. Stalin had masterfully manipulated his allies, and claimed, through the blood spent by the millions who pushed back the Nazi forces, that he merited control of the territories that became part of the Soviet Empire. There was nothing that Churchill (or then Attlee), or Roosevelt, rapidly fading (and then Truman) could do.

The historical assessment is one of a Great Betrayal – which it surely was, in the sense that the Poles were misled by the promises of Churchill and Roosevelt, and in the self-delusion that the two leaders had that, because Stalin was fighting Hitler alongside them, he was actually one of the team, a man they could cooperate with, and someone who had tamed his oppressive and murderous instincts that were so evident from before the war. But whether the ‘Soviet armies’ deserved sympathy for their halt on the Vistula is quite another question. It was probable that most of the Ivans in the Soviet armed forces were heartily sick of Communism, and the havoc it had brought to their homes and families, but were instead conscripted and forced to fight out of fear for what might happen if they resisted. By then, fighting for Mother Russia, and out of hatred for the Germans because of the devastation the latter had wrought on their homeland, they were brought to a halt before Warsaw to avoid a clash that may have been premature. But they were Communists by identification, not by conviction. Stalin was the sole man in charge. He was ruthless: he was going to eliminate the Home Army anyway: why not let the Germans do the job?

Alan Clark’s summing-up ran as follows: “The story of the Warsaw uprising illustrates many features of the later history of World War II. The alternating perfidy and impotence of the western Allies; the alternating brutality and sail-trimming of the SS; the constancy of Soviet power and ambition. Above all, perhaps, it shows the quality of the people for whom nominally, and originally, the war had been fought and how the two dictatorships could still find common ground in the need to suppress them.”

The Allies in Italy

- Military Operations

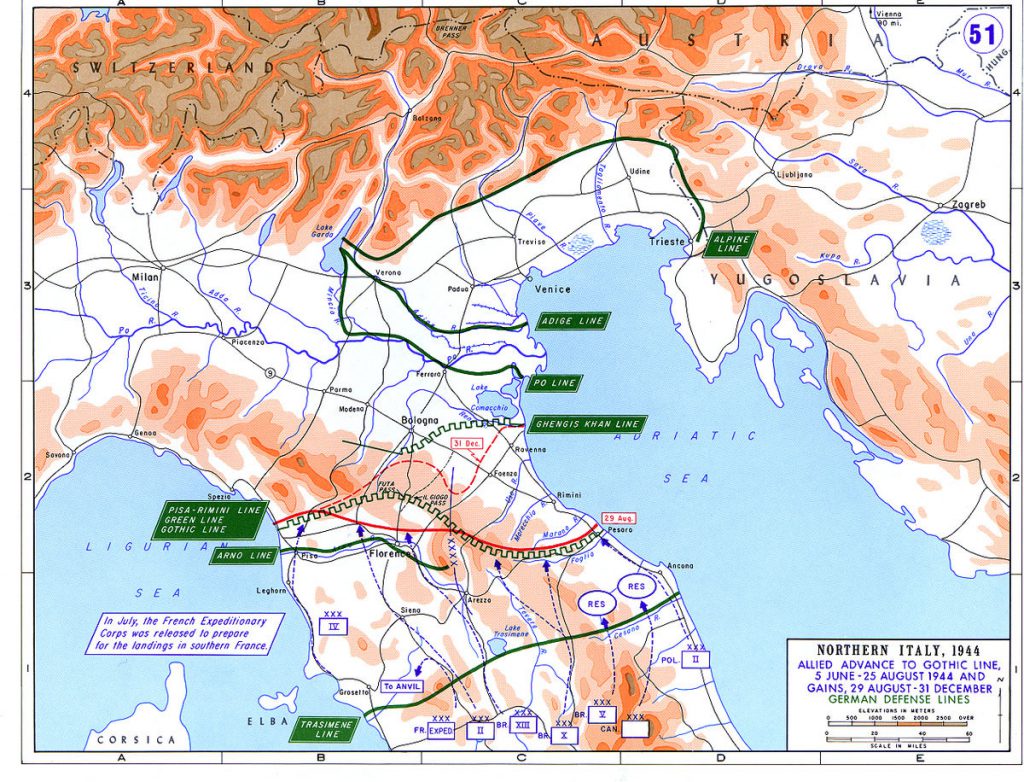

The invasion of Italy (starting with Operation ‘Husky’, the invasion of Sicily) had always been Churchill’s favoured project, since he regarded it as an easier way to repel the Germans and occupy central Europe before Stalin reached it. It was the western Allies’ first foray into Axis-controlled territory, and had been endorsed by Churchill and Roosevelt at Casablanca in January 1943. Under General Alexander, British and American troops had landed in Sicily in July 1943, and on the mainland, at Salerno, two months later. Yet it was always something of a maverick operation: the Teheran Agreement made no mention of it as a diversionary initiative, and thereafter the assault was regularly liable to having troops withdrawn for the more official invasion of Southern France (Operation Anvil, modified to Dragoon). This strategy rebounded in a perhaps predictable way: Hitler maintained troops in Italy to ward off the offensive, thus contributing to Overlord’s success, but the resistance that Alexander’s Army encountered meant that the progress in liberating Italy occurred much more slowly than its architects had forecast.

Enthusiasm for the Italian venture had initially been shared by the Americans and the British, and was confirmed at the TRIDENT conference in Washington in May 1943. At this stage, the British Chiefs of Staff hoped to conclude the war in a year’s time, believing that a march up Italy would be achieved practically unopposed, with the goal of reaching the ‘Ljubljana Gap’ (which was probably a more durable obstacle than the ‘Watford’, or even the ‘Cumberland’ Gap) and striking at the southern portions of Hitler’s Empire before the Soviets arrived there. Yet, as plans advanced, the British brio was tempered by American scepticism. After the Sicilian campaign, the Allied forces were thwarted by issues of terrain, a surprising German resurgence, and a lack of coordination of American and British divisions. In essence, clear strategic goals had not been set, nor processes by which they might be achieved.

Matters were complicated in September 1943 by the ouster of Mussolini, the escape of King Emanuel and General Badoglio to Brindisi, to lead a non-fascist government in the south, and the rescue of Mussolini by Nazi paratroopers so that he could be installed as head of a puppet government in Salò in the North. An armistice between the southern Italians and the Allies was announced (September 3) the day before troops landed at Salerno. The invading forces were now faced with an uncertain ally in the south, not fully trusted because of its past associations with Mussolini’s government, and a revitalized foe in the north. Hitler was determined to defend the territory, had moved sixteen divisions into Italy, and started a reign of terror against both the civilian population and the remnants of the Italian army, thousands of whom were extracted to Germany to work as slaves or be incarcerated.

The period between the armistice and D-Day was thus a perpetual struggle. As the demands for landing-craft and troops to support Overlord increased, morale in Alexander’s Army declined, and progress was tortuously slow, as evidenced by the highly controversial capture of Monte Cassino between January and May 1944, where the Polish Army sustained 6,000 casualties. The British Chiefs of Staff continually challenged the agreement made in Quebec that the Anvil attack was of the highest priority (and even received support from Eisenhower for a while). Moreover, the Allies did not handle the civilian populace very shrewdly, with widescale bombing undermining the suggestion that they had arrived as ’liberators’. With a valiant push, Rome was captured on June 4, by American forces, but a rivalry between the vain and glory-seeking General Clark and the sometimes timid General Alexander meant that the advantage was not hammered home. The dispute over Anvil had to be settled by Roosevelt himself in June. In the summer of 1944, the Allies faced another major defensive obstacle, the Gothic Line, which ran along the Apennines from Spezia to Pesari. Bologna, the city at the center of this discussion, lay about forty miles north of this redoubt. And there the Allied forces stalled.

- Political Goals

The Allies were unanimous that they wanted to install a democratic, non-fascist government in Italy at the conclusion of the war, but did not really define what shape it should take, or understand who among the various factions claiming ideological leadership might contribute. Certainly, the British feared an infusion of Communism into the mix. ‘Anti-fascism’ had a durable odour of ‘communism’ about it, and there was no doubt that strong communist organisations existed both in the industrial towns and in the resistance groups that had escaped to the mountains or the countryside. (After the armistice, a multi-party political committee had been formed with the name of the ‘Committee of National Liberation’, a name that was exactly echoed a few months later by the Soviets’ puppets in Chelm, Poland.) Moreover, while the Foreign Office, epitomised by the vain and ineffectual Anthony Eden, who still harboured a grudge with Mussolini over the Ethiopian wars, expressed a general disdain about the Italians, the Americans were less interested in the fate of individual European nations. Roosevelt’s main focus was on ‘getting his boys home’, and then concentrating on building World Peace with Stalin through the United Nations. The OSS, however, modelled on Britain’s SOE, had more overt communist sympathies.

Yet there existed also rivalry between the USA and Great Britain about post-war goals. The British were looking to control the Mediterranean to protect its colonial routes: the Americans generally tried to undermine such imperial pretensions, and were looking out for their own commercial advantages when hostilities ceased. At this time, Roosevelt and Churchill were starting to disagree more about tactics, and the fate of individual nations, as the debate over Poland, and Roosevelt’s secret parleys with Stalin, showed. Churchill was much more suspicious of Soviet intrigues at this time, although it did not stop him groveling to Stalin, or singing his praises in more sentimental moments.

The result was a high degree of mutual distrust between the Allies and its new partners, the southern Italians, and those resisting Nazi oppression in the north. As Caroline Moorehead aptly puts it, in her very recent House in the Mountains: “Now the cold wariness of the British liberating troops puzzled them. It was, noted Harold Macmillan, ‘one vast headache, with all give and no take’. How much money would have to be spent in order to prevent ‘disease and unrest’? How much aid was going to be necessary to make the Italians militarily useful in the campaign for liberation? And what was the right approach to take towards a country which was at once a defeated enemy and a co-belligerent which expected to be treated as an ally?”

- The Partisans

The partisans in northern Italy, like almost all such groups in occupied Europe, were of very mixed origins, holding multitudinous objectives. But here they were especially motley, containing absconders from the domestic Italian Army, resisting deportation by the Nazis, escaped prisoners-of-war, trying to find a way back to Allied lines, non-Germans conscripted by the Wehrmacht, who had escaped but were uncertain where to turn next, refugees from armies that had fought in the east, earnest civilians distraught over missing loved ones, Jews suddenly threatened by Mussolini’s support of Hitler’s anti-Semitic persecution, the ideologically dedicated, as well as young adventurists, bandits, thieves and terrorists. As a report from Alexander’s staff said: “Bands exist of every degree, down to gangs of thugs who don a partisan cloak of respectability to conceal the nakedness of their brigandage, and bands who bury their arms in their back gardens and only dig them up and festoon themselves in comic opera uniforms when the first Allied troops arrive.” It was thus challenging to find a way to deal consistently with such groups, scattered broadly around the mountainous terrain.

The British generally disapproved of irregular armies, and preferred the partisans to continue the important work of helping POWs escape to Switzerland, where they were able to pass on valuable information to the SIS and OSS offices there. As Richard Lamb wrote: “However, the Allies wanted the partisan activities to be confined to sabotage, facilitating the escape of POWs, and gathering intelligence about the Germans.” Sabotage was encouraged, because its perpetrators could not easily be identified, and it helped the war effort, while direct attacks on German forces could result in fearful reprisals – a phenomenon that took on increasing significance. Hitler had given instructions to the highly experienced General Kesselring that any such assaults should be responded to with ruthless killing of hostages.

Yet the political agitators in the partisans were dominated by communists – who continuously quarreled with the non-communists. The British did not want a repeat of what had happened in Yugoslavia and Greece, where irredentists had established separate control. The CLN had set up a Northern Italian section (the CLNAI) in January 1944, and had made overt claims for political control of some remote areas, seeing itself as the third leg of government. Thus the British were suspicious, and held off infiltrating SOE liaison officers, and parachuting in weapons and supplies, with the first delivery not occurring until December 1943. This encouraged the partisans to think that the Allies were not interested in widespread resistance, and were fearful of communism – which was largely (but not absolutely) true. Tellingly, on July 27, 1944, in the light of Soviet’s expansive colonial intentions, Chief of the Imperial General Staff Alan Brooke first voiced the opinion that Britain might need to view Germany as a future ally against the Soviets.

Churchill expressed outwardly hostile opinions on the partisans in a speech to the House of Commons on February 22, 1944, and his support for Badoglio (and, indirectly, the monarchy) laid him open to the same criticisms of anti-democratic spirit that would bedevil his attitude towards Greece. Ironically, it was the arrival of the Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti from Moscow in March 1944, and his subsequent decision to join Badoglio’s government, that helped to repair some of the discord. In May, many more OSS and SOE officers were flown in, and acts of sabotage increased. This interrupted the German war effort considerably, as Kesselring admitted a few years later. Thus, as summer drew on, the partisans had expectations of a big push to defeat and expel the Germans. By June, all Italian partisan forces were co-ordinated into a collective command structure. They were told by their SOE liaison officers that a break through the Gothic Line would take place in September.

Meanwhile, the confusion in the British camp had become intense. Churchill dithered with his Chiefs of Staff about the competing demands of Italy and France. General Maitland Wilson, who had replaced Eisenhower as the Supreme Commander in the Mediterranean in January 1944, was in June forecasting the entry into Trieste and Ljubljana by September, apparently unaware of the Anvil plans. He was brought back to earth by Eisenhower. At the beginning of August 1944, Alexander’s forces were reduced from 250,000 to 153,000 men, because of the needs in France. Yet Churchill continued to place demands on Alexander, and privately railed over the Anvil decision. Badoglio was replaced by Bonomi, to Churchill’s disappointment. Alexander said his troops were demoralized. There was discord between SOE and the OSS, as well as between SOE and the Foreign Office. It was at this juncture that the controversy started.

- Offensive Strategy

On June 7, Alexander had made a radio appeal to the partisans, encouraging sabotage. As Iris Origo reported it in, in War in Val D’orcia (written soon after the events, in 1947): “General Alexander issues a broadcast to the Italian patriots, telling them that the hour of their rising has come at last. They are to cut the German Army communications wherever possible, by destroying roads, bridges, railways, telegraph-wires. They are to form ambushes and cut off retreating Germans – and to give shelter to Volksdeutsche who have deserted from the German Army. Workmen are urged to sabotage, soldiers and police to desert, ‘collaborators of fascism’ to take this last chance of showing their patriotism and helping the cause of their country’s deliverance. United, we shall attain victory.”

This was an enormously significant proclamation, given what Alexander must have known about the proposed reduction in forces, and what his intelligence sources must have told him about Nazi reprisals. They were surely not words Alexander had crafted himself. One can conclude that it was perhaps part of the general propaganda campaign, current with the D-Day landings, to focus the attention of Nazi forces around Europe on the local threats. Indeed the Political Warfare Executive made a proposal to Eisenhower intended to ‘stimulate . . . strikes, guerilla action and armed uprisings behind the enemy lines’. Historians have accepted that such an initiative would have endangered many civilian lives. The exact follow-up to this recommendation, and how it was manifested in BBC broadcasts in different languages, is outside my current scope, but Origo’s diary entry shows how eagerly the broadcasts from London were followed.

What is highly significant is that General Alexander, in the summer of 1944, was involved in an auxiliary deception operation codenamed ‘Otrington’, which was designed to lead the Germans to think that an attack was going to take place on the Nazi flanks in Genoa and Rimini, as opposed to the south of France, and also as a feint for Alexander’s planned attack through the central Apennines north of Florence. (This was all part of the grander ‘Bodyguard’ deception plan for Overlord.) Yet in August 1944, such plans were changed when General Sir Oliver Leese, now commanding the Eighth Army, persuaded Alexander to move his forces away from the central Apennines over to the Adriatic sector, for an attack on August 25. The Germans were misled to the extent that they had moved forces to the Adriatic, thus confusing Leese’s initiative. Moreover, the historian on whom we rely for this exposition was Professor Sir Michael Howard himself – in his Chapter 7 of Volume 5 of the British Intelligence history. Yet the author makes no reference here to Alexander’s communications to the partisans, or how such signals related to the deception exercise, merely laconically noting: “The attack, after its initial success, was gradually brought to a halt [by Kesselring], and Allied operations in Italy bogged down for another winter.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the message provoked even further animosity from the Germans when Alexander made three separate broadcasts through the BBC, on June 19, 20 and 27, where he encouraged Italian partisans to ‘shoot Germans in the back’. The response from Kesselring, who of course heard the open declaration, was instantaneous. He issued an order on June 20 that read, partially, as follows: “Whenever there is evidence of considerable numbers of partisan groups a proportion of the male population of the area will be arrested, and in the event of an act of violence these men will be shot. The population must be informed of this. Should troops etc. be fired at from any village, the village will be burnt down. Perpetrators or ringleaders will be hanged in public.”

The outcome of this was that a horrible series of massacres occurred during August and September, leading to the worst of all, that at Marzabotto, on September 29 and 30. A more specific order by the German 5 Corps was issued on August 9, with instructions as to how local populations would be assembled to witness the shootings. Yet this was not a new phenomenon: fascist troops had been killing partisan bands and their abettors for the past year in the North. The requirement for Mussolini’s neo-fascist government to recruit young men for its military and police forces prompted thousands to run for the mountains and join the partisans. Italy was now engaged in a civil war, and in the north Italians had been killing other Italians. One of the most infamous of the massacres had occurred in Rome, in March 1944, at the Ardeatine Caves. A Communist Patriotic Action Group had killed 33 German soldiers in the Via Rasella, and ten times that many hostages were killed the next day as a form of reprisal. The summer of 1944 was the bitterest time for executions of Italians: 7500 civilians were killed between March 1944 and April 1945, and 5000 of these met their deaths in the summer months of 1944.

The records show that support for the partisans had been consistent up until September, although demands had sharply risen. “In July 1944 SOE was operating 16 radio stations behind enemy lines, and its missions rose from 23 in August to 33 in September; meanwhile the OSS had 12 in place, plus another 6 ready to leave. Contacts between Allied teams and partisan formations made large-scale airdrops of supplies possible. In May 1944, 152 tons were dropped; 361 tons were delivered in June, 446 tons in July, 227 tons in August, and 252 tons in September.” (Battistelli and Crociani) Yet those authors offer up another explanation: Operation ‘Olive’ which began on August 25, at the Adriatic end of the Gothic Line, provoked a severe response against partisans in the north-west. The fierce German reprisals that then took place (on partisans and civilians, including the Marzobotto massacre) by the SS Panzer Green Division Reichsführer contributed to the demoralization of the partisan forces, and 47,000 handed themselves in after an amnesty offer by the RSI on October 28.

What is not clear is why the partisans continued to engage in such desperate actions. Had they become desperadoes? As Battistelli and Crociani write, a period of crisis had arrived: “In mid-September 1944 the partisans’ war was, for all practical purposes, at a standstill. The influx of would-be recruits made it impossible for the Allies to arm them all; many of the premature ‘free zones’ were being retaken by the Germans; true insurgency was not possible without direct Allied support; and, despite attacks by the US Fifth and British Eighth Armies against the Gothic Line from 12 September, progress would be slow and mainly up the Adriatic flank. Against the advice of Allied liaison officers, the partisan reaction was, inexplicably, to declare more ‘free zones’.” Things appeared to be out of control. Battistelli and Crociani further analyse it as follows: “The summer of 1944 thus represented a turning-point in partisan activity, after which sabotage and attacks against communications decreased in favour of first looting and then attacks against Axis troops, both being necessary to obtain food and weapons to enable large formations to carry on their war.” And it thus led to the deadliest massacre at Marzabotto, south of Bologna, where the SS, under Sturmbannführer Walter Reder, shot about 770 men, women, and children.

The wholesale deaths even provoked Mussolini to beg the SS to back off. On November 13 Alexander issued a belated communiqué encouraging the partisans to disarm for the winter, as the campaign was effectively coming to a halt. Alexander’s advice was largely ignored: the partisans viewed it a political move executed out of disdain for communism. The Germans viewed it as a sign of weakness, and it deterred any thoughts of immediate surrender. Thus the activity of the partisans continued, but less vigorously, as air support in the way of supplies had already begun to dwindle. And another significant factor was at work. Before he left Moscow, Togliatti, the newly arrived Communist leader, had made an appeal to the Italian resistance movement to take up arms against the Fascists. Yet when he arrived in Italy in March 1944, Togliatti had submerged the militant aspects of his PCI (Communist Party of Italy) in the cause of unity and democracy, and had the Garibaldi (Communist) brigades disarmed. Moorehead points out that the Northern partisans were effectively stunned and weakened by Togliatti’s strategic move to make the Communists appear less harmful as the country prepared for postwar government.

In addition, roles changed. Not just the arrival of General Leese, and his disruption of careful deception plans. General George Marshall, the US Chief of Staff, took the view that Italy was ‘an expensive sideshow’ (Brian Holden Reid). In December, Alexander had to tried to breathe fresh life into the plan to assault the Ljubljana Gap, but after the Yalta Conference of February 1945, Alexander, now Supreme Commander in the Mediterranean, was instructed simply to ensure that the maximum number of German divisions were held down, thus allowing the progress by Allied troops in France and Germany to be maintained. Bologna was not taken until April 1945, after which the reprisals against fascists began. Perhaps three thousand were killed there by the partisans.

- The Aftermath

The massacres of September and October 1944 have not been forgotten, but their circumstances have tended to be overlooked in the histories. It is difficult to find a sharp and incisive analysis of British strategy and communications at this time. Norman Davies writes about the parallel activities in Poland and Italy in the summer of 1944 in No Simple Victory, but I would suggest that he does not do justice to the situation. He blames General Alexander for ‘opening the floodgates for a second wave of German revenge’ when he publicly announced that there would be no winter offensive in 1944-45, but it was highly unlikely that that ‘unoriginal thinker’ (Oxford Companion to Word War II) would have been allowed to come up with such a message without guidance and approval. Davies points to ‘differences of opinion between British and American strategists’, which allowed German commanders to be given a free hand to take ruthless action against the partisans’. So why were the differences not resolved by Eisenhower? Moreover, while oppression against the partisans did intensify, the worst reprisals against civilians that Davies refers to were over by then.

Had Alexander severely misled the partisans in his encouragement that their ‘hour of rising’ had come at last? What was intended by his open bloodthirsty call to kill Nazis in the back? Did the partisans really pursue such aggressive attacks because of Alexander’s provocative words, or, did they engage in them in full knowledge of the carnage it would cause, trying to prove, perhaps, that a fierce and autocratic form of government was the only method of eliminating fascism? Were the local SOE officers responsible for encouraging attacks on German troops in order to secure weapons and food? Why could Togliatti not maintain any control over the communists? And what was Alexander’s intention in calling the forces to hold up for the winter, knowing that the Germans would pick up that message? Whatever the reality, it was not a very honourable episode in the British war effort. Too many organisations arguing amongst themselves, no doubt. Churchill had many things on his mind, but it was another example of where he wavered on strategy, then became too involved in details, or followed his buccaneering instincts, and afterwards turned sentimental at inappropriate times. Yet Eisenhower was the Supreme Commander, and clearly had problems in enforcing a disciplined approach to strategy.

At least the horrendous reprisals ceased. Maybe, as in Warsaw, the SS realised that the war was going to be lost, and that war crimes tribunals would investigate the legality of the massacre of innocent civilians. Yet a few grisly murders continued. Internecine feuds continued among the partisans during the winter of 1944-45, with fears of collaborators and spies in the midst, and frequently individuals who opposed communism were persecuted and killed. It is beyond the scope of this article to describe the events of this winter in the north (see Moorehead for more details), but a few statements need to be made. The number of partisans did decline sharply to begin with, but then ascended in the spring. More supplies were dropped by SOE, but the latter’s anti-communist message intensified, and the organisation tried to direct weaponry to non-communist units. Savage reprisals by the fascists did take place, but not on the scale of the September massacres. In the end, the communists managed to emerge from World War II with a large amount of prestige, because they ensured that they were present to liberate finally the cities of Turin, Milan, and Bologna in concert with the Allied forces that eventually broke through, even though they were merciless with fascists who had remained loyal to Mussolini and the Nazis. As with Spain, the memories of civil war and different allegiances stayed and festered for a long time.

And the communists actually survived and thrived, as Howard’s encounter forty years later proved – a dramatic difference from the possibility of independent democratic organisations in Warsaw enduring after the war, for example. Moreover, they obviously held a grudge. Yet history continues to be distorted. Views contrary to the betrayal of such ‘liberating’ communists have been expressed. In his book The Pursuit of Italy David Gilmour writes: “At the entrance of the town hall of Bologna photographs are still displayed of partisans liberating the city without giving a hint that Allied forces had helped them to do so.” He goes on to point out that, after the massacre of the Ardeatine Caves, many Italians were of the opinion that those responsible (Communists) should have given them up for execution instead. Others claim that the murders of the German soldiers were not actually communists: Moorhead claims they were mainly ‘students’. It all gets very murky. I leave the epitaph to Nicola Bianca: “The fact is that brutalization was a much part of the Italian wars as of any other, even if it was these same wars which made possible the birth of the first true democracy the country had known.”

Reassessment of Howard’s Judgment

Professor Howard seemed to be drawing an equivalence between, on the one hand, the desire for the Red Army to have the Nazis perform their dirty work for them by eliminating a nominal ally but a social enemy (the Home Army), and thus disengage from an attack on Warsaw, and, on the other, a strained Allied Army, with its resources strategically depleted, reneging on commitments to provide material support to a scattered force of anti-fascist sympathisers, some of whom it regarded as dangerous for the long-term health of the invading country, as well as that of the nation it was attempting to liberate. This is highly unbalanced, as the Home Army had few choices, whereas the Italian partisans had time and territory on their side. They did not have to engage in bloody attacks that would provoke reprisals of innocents. The Allies in Italy were trying to liberate a country that had waged warfare against them: the Soviet Army refused to assist insurgents who were supposedly fighting the same enemy. The British, certainly, were determined to weaken the Communists: why was Howard surprised by this? And, if he had a case to make, he could have criticised the British Army and its propagandists back in London for obvious lapses in communications rather than switching his attention to expressing sympathy for the communists outside Warsaw. Was he loath to analyse what Alexander had done simply because he had served under him?

It is informative to parse carefully the phrases Howard uses in his outburst. I present the text again here, for ease of reference:

“In September 1944, believing that the end of the war was in sight, the Allied High Command had issued orders for the Italian partisans to unmask themselves and attack German communications throughout the north of Italy. They did so, including those on and around Monte Sole. The Germans reacted with predictable savagery. The Allied armies did not come to their help, and the partisan movement in North Italy was largely destroyed. It was still believed – and especially in Bologna, where the communists had governed the city ever since the war – that this had been deliberately planned by the Allies in order to weaken the communist movement, much as the Soviets had encouraged the people of Warsaw to rise and then sat by while the Germans exterminated them. When I protested to my hosts that this was an outrageous explanation and that there was nothing that we could have done, they smiled politely. But I was left wondering, as I wondered about poor Terry, was there really nothing that we could have done to help? Were there no risks that our huge cumbrous armies with their vast supply-lines might have taken if we knew what was going on? – and someone must have known what was going on. Probably not: but ever since then I have been sparing of criticism of the Soviet armies for their halt before Warsaw.”

‘In September 1944, believing that the end of the war was in sight, the Allied High Command . . ’

Did the incitement actually happen in September, as opposed to June? What was the source, and who actually issued the order? What did that ‘in sight’ mean? It is a woolly, evasive term. Who actually believed that the war would end shortly? Were these orders issued over public radio (for the Germans to hear), or privately, to SOE and OSS representatives?

‘ . . had issued orders to unmask themselves’.

What does that mean? Take off their camouflage and engage in open warfare? The Allied High Command could in fact not ‘order’ the partisans to do anything, but why would an ‘order’ be issued to do that? I can find no evidence for it in the transcripts.

‘ . . .and attack German communications’.

An incitement to sabotage was fine, and consistent, but the communication specifically did not encourage murder of fascist forces, whether Italian or German. Alexander admittedly did so in June, but Howard does not cite those broadcasts.

‘The Germans reacted with predictable savagery.’

The Germans engaged in savage reprisals primarily in August, before the supposed order that Howard quotes. The reprisals took place because of partisan murders of soldiers, and in response to Operation ‘Olive’, not simply because of attacks on communications, as Howard suggests here. Moreover, the massacre at Marzabotto occurred at the end of September, when Kesselring had mollified his instructions, after Mussolini’s intervention.

‘Allied armies did not come to their help’.

But was anything more than parachuting in supplies expected? Over an area of more than 30,000 square miles, behind enemy lines? Bologna only? Where is the evidence – beyond the June message quoted by Origo? What did the SOE officers say? (I have not yet read Joe Maioli’s Mission Accomplished: SOE in Italy 1943-45, although its title suggests success, not failure.)

‘The partisan movement in northern Italy was largely destroyed’.

This was not true, as numerous memoirs and histories indicate. Admittedly, activity sharply decreased after September, because of the Nazi attacks, and the reduction in supplies. It thus suffered in the short term, but the movement became highly active again in the spring of 1945. On what did Howard base his conclusion? And why did he not mention that it was the Communist Togliatti who had been as much responsible for any weakening in the autumn of 1944? Or that Italian neo-fascists had been determinedly hunting down partisans all year?

‘It was still believed . . .’

Why the passive voice? Who? When? Why? Of course the communists in Bologna would say that.

‘ . . .deliberately planned to weaken the communist movement’.

Richard Lamb wrote that Field Marshal Harding, Alexander’s Chief of Staff, had told him that the controversial Proclama Alexander, interpreted by some Italian historians as an anti-communist move, had been designed to protect the partisans. But that proclamation was made in November, and it encouraged partisans to suspend hostilities. In any case, weakening the communist movement was not a dishonourable goal, considering what was happening elsewhere in Europe.

‘. . . much as the Soviets had encouraged the people of Warsaw to rise and then sat by while the Germans exterminated them’.

Did the Bologna communists really make this analogy, condemning the actions of communists in Poland as if they were akin to the actions of the Allies? Expressing sympathy for the class enemies of the Polish Home Army would have been heresy. Why could Howard not refute it at the time, or point out the contradictions in this passage?

‘ . . .was there really nothing that we could have done to help?’

Aren’t you the one supposed to be answering the questions, Professor, not asking them?

‘. . . huge cumbrous armies with their vast supply-lines’

Why had Howard forgotten about the depletion of resources in Italy, the decision to hold ground, and what he wrote about in Strategic Deception? Did he really think that Alexander would have been able to ignore Eisenhower’s directives? And why ’cumbrous’ – unwieldy? inflexible?

‘Someone must have known what was going on’.

Indeed. And shouldn’t it have been Howard’s responsibility to find out?

‘Ever since then I have been sparing of criticism of the Soviet armies’

Where? In print? In conversations? What has one got to do with the other? Why should an implicit criticism of the Allied Command be converted into sympathy for Stalin?

The irony is that the Allied Command, perhaps guided by the Political Warfare Executive, did probably woefully mismanage expectations, and encourage attacks on German troops that resulted in the murder of innocent civilians. But Howard does not make this case. Those events happened primarily in the June through August period, while Howard bases his argument on a September proclamation. He was very quick to accept the Bologna communists’ claim that the alleged ‘destruction’ of the partisans was all the Allies’ fault, when the partisans themselves, northern Italian fascists, the SS troops, Togliatti, and even the Pope, held some responsibility. If Howard had other evidence, he should have presented it.

Why was Howard not aware of the Monte Sole massacre at the time? Why did he not perform research before walking into the meeting in Bologna? What did the communists there tell him that convinced him that they had been hard done by? Did they blame the British for the SS reprisals? Why was he taken in by the relentless propagandizing of the Communists? Why did he not explain what he thought the parallels were between Alexander’s actions and those of Rokossovsky? The episode offered an intriguing opportunity to investigate Allied strategy in Italy and Poland in the approach to D-Day and afterwards, but Howard fumbled it, and an enormous amount is thus missing from his casual observations. He could have illustrated how the attempts by the Western Allies to protect the incursions into Europe had unintended consequences, and shown the result of the competition between western intelligence and Togliatti for the allegiance of the Italian partisans. Instead the illustrious historian never did his homework. He obfuscated rather than illuminated, indulging in vague speculation, shaky chronology, ineffectual hand-wringing, and unsupported conclusions.

Perhaps a pertinent epitaph is what Howard himself wrote, in his volume of Strategic Deception, about the campaign in India (p 221): “The real problem which confronted the British deception staff in India, however, was that created by its own side; the continuing uncertainty as to what Allied strategic intentions really were. In default of any actual plans the best that the deceivers could do as one of them ruefully put it, was to ensure that the enemy remained as confused as they were themselves.” He had an excellent opportunity to inspect the Italian campaign as a case study for the same phenomenon, but for some reason avoided it.

This has been a fascinating and educational, though ultimately sterile, exercise for me. It certainly did not help me understand why Howard is held in such regard as a historian. ‘Why are eminent figures allowed to get away with such feeble analysis?’, I asked myself. Is it because they are distinguished, and an aura of authority has descended upon them? Or am I completely out to lunch? No doubt I should read more of Howard’s works. But ars longa, vita brevis . . .

Sources:

War in Italy 1943-1945, A Brutal Story by Richard Lamb

Russia at War 1941-1945 by Nicholas Werth

Barbarossa by Alan Clark

The Second World War by Antony Beevor

War in Val D’Orcia by Iris Origo

Captain Professor by Michael Howard

The House in the Mountains by Caroline Moorehead

World War II Partisan Warfare in Italy by Pier Paola Battistelli & Piero Crociani

The Pursuit of Italy by David Gilmour

Between Giants by Prit Buttar

Winston Churchill: Road to Victory 1941-1945 by Martin Gilbert

Rising ’47 by Norman Davies

No Simple Victory by Norman Davies

The Oxford Companion to World War II edited by Ian Dear and M. R. E. Foot

The Oxford Illustrated History of World War II edited by Paul Overy

British Intelligence in the Second World War, Volume 5, Strategic Deception by Michael Howard

(New Commonplace entries may be viewed here.)